Inspiration: a functional approach to creative practice.

PhD thesis in Art, Design & Media, by Gil Dekel.

9.2 Core themes (pt 2 of 2)

While exploring the use of abstract shapes in the process of art making I noted that colours come next. Kandinsky (1972) and Rodchenko (Dabrowski, 1998) have noted the use of colour for its inner qualities that are not necessarily connected to the surface. Colours are used by artists for their inner quality, or as inner messages that come within colour, in what can be called ‘abstract colours’. Felice (![]()

![]() paras. 18-19) for example, asserted that colours have a dual quality to them that can be used in art. Felice explains that colours are usually regarded for the emotion that they convey once people see them. Yet, he asserts another quality to colour, that of having an active creative process with nature itself, regardless of the observer. Colours are absorbed and altered in relation to the surfaces on which they are applied, to an extent that colour seems to assume a role with reality which is more prevailing than the role colour assumes in art once being observed by audiences, as he (

paras. 18-19) for example, asserted that colours have a dual quality to them that can be used in art. Felice explains that colours are usually regarded for the emotion that they convey once people see them. Yet, he asserts another quality to colour, that of having an active creative process with nature itself, regardless of the observer. Colours are absorbed and altered in relation to the surfaces on which they are applied, to an extent that colour seems to assume a role with reality which is more prevailing than the role colour assumes in art once being observed by audiences, as he (![]()

![]() para. 12) explains:

para. 12) explains:

‘Painting… it is not born to create specific shapes that need to satisfy the viewer. The paintings are not defined by the understanding of the viewer or what the viewer sees, but rather exist in their own right, and have their own relation to the three-dimensional space in which they were created.’

In that respect I have examined colours not with regard to their visible influence on the viewer’s senses, but rather to their inner independent quality with reality, which artists seem to assert. I have concluded that the use of colour by artists comes to create a sense of movement of inner emotions into the external reality. I focused on vivid colours and transparent for their quality of generating movement, which became a theme in chapter 11:

Chapter 10: Stimulation (Sensing–Feeling–Acknowledging). Chapter 11: Internalisation (Shape–Movement). Chapter 12: Application (Place–Space).

Likewise, my paper presentations in the second year of this research evolved from focusing on inner experience to focusing on the process of transformation of initial inspired image to the actual artefact. Feedback on my paper at the 2nd International Arts in Society Conference (Kassel University, Germany, August 2007) has demonstrated the immense interest that a presentation on creative processes can stir. I have presented a few films I created and their development, and feedback suggested that there is a need for further study in that area.

Another important conference I took part in was organised by the Consciousness and Experiential Psychology Section of the British Psychological Society, in Oxford, September 2007. For this conference I have presented a poster, not a ‘paper’. It was the poster that served as the trigger to inspire audiences (while at their half-hour tea break between lectures) to approach me and ask about my research. I then gave a short presentation to the people who gathered around me in a similar way that I would give a paper. However, the interesting part was that my artistic poster was inspiring people to approach me, and not a formal way of sitting in a class and listening to a presenter. The custom of poster presentation is not new in this conference, but is followed each year. For me, this was a first and new form in which I could engage in an intellectual academic discussion, triggered by my artistic art work. This was most suitable to that stage in my research where I evolved to explore processes rather than specific moments of inspiration.

At the same time my paper (Dekel, 2008) on the creative process was accepted for publication in a social sciences qualitative research journal, demonstrating that the creative processes followed by art researchers does not contribute to the art field only but also to such studies as those in the social world.

My artworks shifted from focusing on my own personal experiences to observing the experiences of others. I have begun this shift with the installation work Waterised Words (2007) (see overview in chapter 12.2) which focused on asking audiences what is the taste of water that was ’embedded’ within words.

In another project, What is Love? (2007; ![]() ), I have continued to engage people with questions, this time asking people in the middle of the street, ‘What is love?’ and filming their answers into a short film (see overview chapter 12.1). This project felt like an installation in action, where the final art work was created while it was made, with people’s responses shaping the way my action looked, and the way I continued to ask other people, shaping the feeling of the final film. This project drew from my experience by then with interviewing people, where I have learned that surprising questions which are articulated well can open up people to unique responses. Robson (1993: 234) in his study of research methods describes a method in interviewing which he calls ‘probes’. Probes, he explains, are tactics, such as body gestures that can get the interviewees to expand on the answer they gave. I took this tactic to its extreme, using it for getting an initial response from people, and not a second response that aims to expand on the previous one.

), I have continued to engage people with questions, this time asking people in the middle of the street, ‘What is love?’ and filming their answers into a short film (see overview chapter 12.1). This project felt like an installation in action, where the final art work was created while it was made, with people’s responses shaping the way my action looked, and the way I continued to ask other people, shaping the feeling of the final film. This project drew from my experience by then with interviewing people, where I have learned that surprising questions which are articulated well can open up people to unique responses. Robson (1993: 234) in his study of research methods describes a method in interviewing which he calls ‘probes’. Probes, he explains, are tactics, such as body gestures that can get the interviewees to expand on the answer they gave. I took this tactic to its extreme, using it for getting an initial response from people, and not a second response that aims to expand on the previous one.

By this time my interviews with artists, my paper presentations, and the literature review have shifted from focusing on inner visions and emotions to focusing on the creative process which artists and non-artists seem to follow. My art works moved to become public, not just in the content but also in the context in which they were created. In a way the thesis evolved from the individual to the group, from the inner world of The Prince of Hampshire to the collective world of What is Love?. I also carried out more performances and poetry reading in front of audiences in events that were not directly connected to my research, thus allowing me to expand my work to public audiences (fig. 9).

Figure 9: Gil Dekel at a poetry reading and graphic design presentation, Access Festival 2007, Southampton. Image © Gil Dekel.

By then I had noted the need to express the creative process in public, and I started to wonder about the methods which might be employed in order to facilitate a better use of creativity by people. The first question I asked in that respect was how artists seem to manifest creativity better than most other people do, the so-called ‘non-artists’. The artists that I interviewed suggested that there is no unique or special capacity to being an artist. Rather, they suggested that they have a ‘normal’ relation with life, and that they live in this world, so to speak, and not in an imagined world which is remote from our reality.

Yet, when I examined that form of relationship with life I noted that my interviewees evidenced a specific quality they all share, the quality to sense, to be sensitive to reality. As Wilmer (![]()

![]() para. 57) suggests, his work has ‘… a duty to what exists, to the nature of reality…’ And Katayoun (

para. 57) suggests, his work has ‘… a duty to what exists, to the nature of reality…’ And Katayoun (![]()

![]() para. 28) suggests that ‘first and foremost it is about having a sense of your environment… allowing the internalisation and processing of those images to influence a work of art’. My interviewees exert a very sensitive approach to life, in which they see things that normal people ignore. The poet Lorca (Gibson, 1989: 23) described this as a ‘…straightforward approach to life; looking and listening’.

para. 28) suggests that ‘first and foremost it is about having a sense of your environment… allowing the internalisation and processing of those images to influence a work of art’. My interviewees exert a very sensitive approach to life, in which they see things that normal people ignore. The poet Lorca (Gibson, 1989: 23) described this as a ‘…straightforward approach to life; looking and listening’.

With this conclusion I noticed that there is a core theme, ‘sensing’, which comes even before the individual feelings of the artist come to work. I have included the theme ‘sensing’ at the beginning of chapter 10:

Chapter 10: Stimulation (Sensing–Feeling–Acknowledging). Chapter 11: Internalisation (Shape–Movement). Chapter 12: Application (Place–Space).

With the understanding that the artist has a way of sensing reality, I noted that the access to the creative source requires one to become aware of one’s way of living and perceiving reality around them, as British performer Roger Robinson (BBC Hampshire, 2007) say, ‘the more you are aware of yourself and [commit to it?] the more you are personally empowered’.

The literature that I read shifted to observe artists in various countries and times in order to understand the context of their creativity and thus understand the specific personal way through which they access the creative source. I examined the developments in visual art through history, and have approached artists from outside the UK for my interviews.

My artwork evolved to examine the creative processes, the way that the personality of the artists affects their creativity. The first art work in that respect was Interview with authorial-Self (2007;![]()

![]() ), a work in which I have conducted an interview with my own source of creativity that explains in simple words how do I open up to be inspired as an artist. In a second experiment, made into the film Explorers of the Heart (2007), I have performed my poetry with an actor that joined me, and during the performance we have also answered questions relating to the way that we are inspired to create art. The aim of such works was to explore and share understanding about the way that artists sense reality around them.

), a work in which I have conducted an interview with my own source of creativity that explains in simple words how do I open up to be inspired as an artist. In a second experiment, made into the film Explorers of the Heart (2007), I have performed my poetry with an actor that joined me, and during the performance we have also answered questions relating to the way that we are inspired to create art. The aim of such works was to explore and share understanding about the way that artists sense reality around them.

The questions in my interviews shifted from asking about the nature of the creative process ‘philosophically,’ so to speak, to asking about the personal way in which the artists access the creative power, touching on the social and cultural context.

The findings that arose from the interviews revealed a shared source that seems to come from beyond the conscious mind and logic to inspire the artists. Although differences in social and cultural backgrounds of the interviewees (USA, Canada, Norway, Finland, France, Hungary, Israel, Iran, the Far East, and the UK) they all shared that their personal way of becoming inspired is by way of experiencing life by appreciating it and seeing its beauty. With these commonalities I concluded that the approach of artists that allows for creativity is not a unique skill saved to artists only, but rather a simple approach of experiencing and appreciating. With this finding I concluded that chapter 12 will be named ‘Application’. By application I mean the translation of the artists’ images and emotions through the sense of environment. I do not refer to the actual making of art in the environment, but rather to the influence that the environment has on the shaping of the idea in the mind of the artist. What interests me is the psychology of the creative process.

Under Application I established the core theme ‘place’, suggesting artists’ experience and appreciation of life:

Chapter 10: Stimulation (Sensing–Feeling–Acknowledging). Chapter 11: Internalisation (Shape–Movement). Chapter 12: Application (Place–Space).

My interviewees shared the feeling of appreciation of life and sensing its beauty by experiencing it, not by observing it. Yet, that feeling manifests itself not just through an individuality that is remote from reality, but rather through the individuality which must operate within the collective context of reality. As Katayoun (![]()

![]() para. 38) declares, ‘my art is my life. I do not separate the two’. It is by knowing the individual character of the self that artists assert that they find the ‘gate’ in which they can experience the collective reality. It is a duality in which individuality opens a way for the artist to experience the collective. Varini (

para. 38) declares, ‘my art is my life. I do not separate the two’. It is by knowing the individual character of the self that artists assert that they find the ‘gate’ in which they can experience the collective reality. It is a duality in which individuality opens a way for the artist to experience the collective. Varini (![]()

![]() para. 14) explains the way in which two things may be seen separated yet are integral, using the metaphor of love: ‘When two people are in love they do not love the same person but each other… yet they are perfectly able to understand and share that love’.

para. 14) explains the way in which two things may be seen separated yet are integral, using the metaphor of love: ‘When two people are in love they do not love the same person but each other… yet they are perfectly able to understand and share that love’.

While the research started with the notion of the individual, it evolved into the shared context, and now returned back to the individual that is within a context. Likewise, my art work shifted to examine the duality of the inner individuality expressed as a collective. In Confessions of an Angel (2008; ![]() ) I assert the desire of an artist to know himself through the process of helping others to know themselves. In a subsequent experiment that was made into the film A Fallen Angel (2008;

) I assert the desire of an artist to know himself through the process of helping others to know themselves. In a subsequent experiment that was made into the film A Fallen Angel (2008; ![]() ) I told a short true story of an inner experience I had, to students of Playback Theatre. My experience inspired them to re-enact and perform it with their own input. This form of shared creativity demonstrated how people can learn to draw inwards both as a group and as individuals within a group.

) I told a short true story of an inner experience I had, to students of Playback Theatre. My experience inspired them to re-enact and perform it with their own input. This form of shared creativity demonstrated how people can learn to draw inwards both as a group and as individuals within a group.

At the same time my paper presentations changed from presenting ‘structures’ to more open discussions, adjustable to the context and aiming to explore ways in which the audience can be inspired themselves while I discuss inspiration. In a two-hour long presentation that I gave together with another artist for the Alister Hardy Society (Oxford, March 2008), I have allowed for ample input from the audience, and assumed the role of a facilitator. Although I was the ‘expert’ in the field of art, as feedback suggested, and my presentation shed much light on the topic, I noted that art can elevate audiences, who consider themselves ‘not creative’, to be prolific and fluent in expressing their own insights, using spoken words. It seems that the individual needs merely to be inspired within a group.

I concluded that the function of the artist is simply to focus the awareness and attention of others to the creative process within every person.

However, artists assert that the inner creative process operates not just with the seen or heard inner reality, but also with its absence, mainly silence. ‘I prefer to be quiet when painting’ Chan (![]()

![]() para. 14) explains ‘it is in the silence… that the communion… can take place’. Chan’s experience demonstrates that her communion is conducted through silence, and in that way silence is not seen as a negation, or cancellation, but rather as a new form of communication. For that reason, sound and silence were chosen as core themes addressing the theme ‘space’, in chapter 12:

para. 14) explains ‘it is in the silence… that the communion… can take place’. Chan’s experience demonstrates that her communion is conducted through silence, and in that way silence is not seen as a negation, or cancellation, but rather as a new form of communication. For that reason, sound and silence were chosen as core themes addressing the theme ‘space’, in chapter 12:

Chapter 10: Stimulation (Sensing–Feeling–Acknowledging). Chapter 11: Internalisation (Shape–Movement). Chapter 12: Application (Place–Space).

The sequence of the process in which artists become inspired was concluded for the three chapters: the initial sensing that something exists transforms to a specific feeling within the artists which is then acknowledged with impressions of images and words. Acknowledgement receives artistic abstract shapes, and with it colours that produce a sense of movement. As the creative energy moves it is manifested through the place, the experience of life and its beauty, which allows the artists to perceive a space, an individual character of the shared reality.

The notion of inner reality within the shared reality was explored in a final workshop experiment undertaken for this research (see chapter 14), where I have guided a group of eight individuals that defined themselves as ‘non artists’ to draw inwardly and see if they can connect to inner images and emotions. Each individual worked privately, with his or her eyes closed, yet they all shared the same guidance that I provided, and also produced some remarkable similarities in their works. The experiment indicated that the creative process can be learned and achieved by all people, rather than seen as ‘inherent’ or ‘inspired’ by high forces to some individuals only.

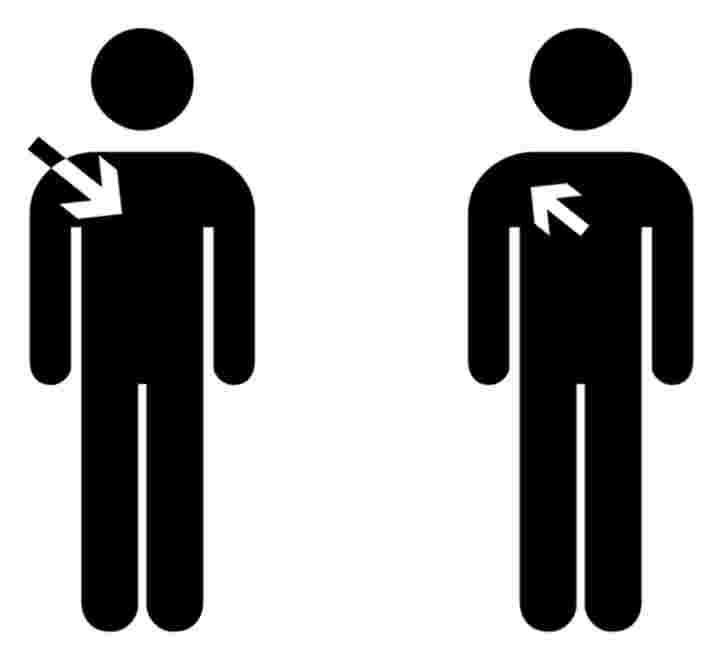

Analysis and reflection of external circumstances, discussed in this chapter, has provided for the core themes of the inspiration process as well as for the workshop experiment. The following chapters (10–14) will demonstrate how these core themes can be approached not from external circumstances only, but from internal circumstances of the artists, looking at them not from the outside but from the inside (see fig. 10).

Figure 10: Graphic illustration of the idea of external influences on the artist (left), and internal influences (right). Image © Gil Dekel.

Table of Content: