Inspiration: a functional approach to creative practice.

PhD thesis in Art, Design & Media, by Gil Dekel.

8.1.1 Phenomenology

8.1.1.1 Agent

Prior to the start of this research, in February 2006, I had two distinct modes of thought. One involved being a creative artist myself, and the other was writing up a PhD proposal (Symbols of Feelings, published December 2006;![]() ). These two states of mind did not coincide. However, as my research progressed I gradually learned to combine the two, allowing practice and theory to feed into each other. During the first few months of this research I had already created a few artworks, and presented my paper at a number of conferences and events (

). These two states of mind did not coincide. However, as my research progressed I gradually learned to combine the two, allowing practice and theory to feed into each other. During the first few months of this research I had already created a few artworks, and presented my paper at a number of conferences and events (![]() actions table). This yielded valuable feedback from audiences in the early stages of the research, referring both to my theoretical ideas and to the artworks, which were presented as part of the papers. As a natural matter I have adopted the phenomenological approach of using the researcher himself as an agent (instead of using structures). The marriage of practice with theory led to a point where practice generated theory, and theory created meanings and explained practice. Since the phenomenological approach gives equal weight to practice and theory, the two could ‘speak to each other’, allowing me to give them equal attention, thereby observing the influence of one on the other. Theory was viewed as a part of the process of making art, and art produced experiences and results that enriched theory. This was especially noticeable in the concluding art experiment for this research (see chapter 14).

actions table). This yielded valuable feedback from audiences in the early stages of the research, referring both to my theoretical ideas and to the artworks, which were presented as part of the papers. As a natural matter I have adopted the phenomenological approach of using the researcher himself as an agent (instead of using structures). The marriage of practice with theory led to a point where practice generated theory, and theory created meanings and explained practice. Since the phenomenological approach gives equal weight to practice and theory, the two could ‘speak to each other’, allowing me to give them equal attention, thereby observing the influence of one on the other. Theory was viewed as a part of the process of making art, and art produced experiences and results that enriched theory. This was especially noticeable in the concluding art experiment for this research (see chapter 14).

8.1.1.2 Deduction/Induction

In the first stages of the research I attempted to examine artistic experiences via a deductive approach, trying to generate theory based on theory. I looked at Kant’s ([1781] 1964) a-priori knowledge, Descartes’ ([1630–1701] 1972) notion of epistemology based on the act of thinking (rather than on the act of feeling), and Einstein’s (1962) explanations of the fluidity and relativity of experiences of time and space. These theories, together with quantum physics, did prove valuable for this research, although not in a way that I had expected. I was unable to deduce from these theories a conclusion relating to the activity of artistic inspiration. However, I was able to conclude through these theories that there exist possibilities for unseen capacities that transcend our normal perceptions. The deductive approach through scientific theories, together with my discussions with scientists and via attending scientific conferences, did not say much about artistic creativity. Instead, an inductive approach, which allows for intensive and in–depth research, was chosen.

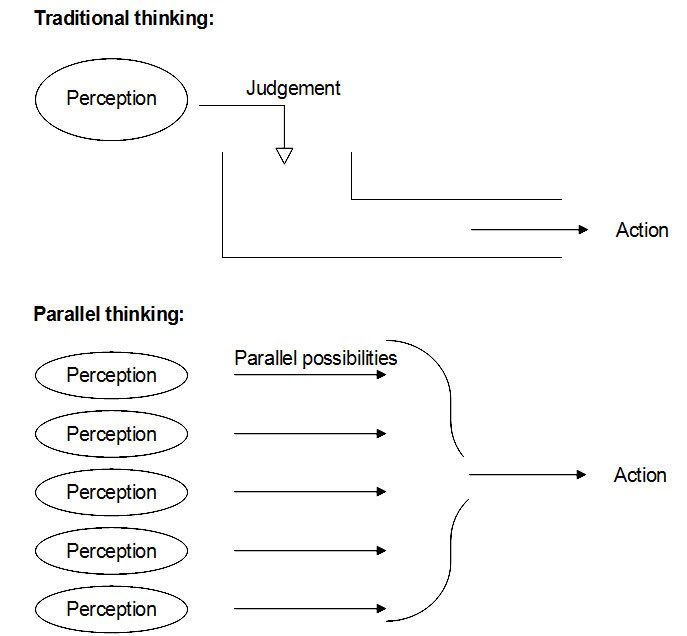

Edward de Bono, in his book Parallel Thinking ([1994] 1995), developed a useful method for induction research. de Bono does not just assert a system, but also scans the current system in use. He explains that the current mode of thinking, which he calls traditional thinking, uses judgement (yes/no, right/wrong, true/false) as a tool to eliminate some information and thus arrive at one conclusion. de Bono suggests an alternative method, parallel thinking, which embraces both sides of contradictions and seeks to design a way forward (see diagram 1). In that way, de Bono ([1994] 1995: 57) argues, we can design and create through possibilities, rather than take ideas apart through analysis and logic. This approach was used in my research through an interdisciplinary literature review, consisting mainly of art studies, with references to psychology, philosophy, and science, for the purpose of designing conclusions gained from a method of parallel embracement. The research also saw an interdisciplinary approach by being a practitioner in many fields of art, ranging from making poetry, films, graphic design, installations, and art workshops.

I have also interviewed artists across a few sectors of the arts – poets, painters, installation artists, chanting artists, authors, critics, and academics.

Diagram 1: Illustration of de Bono’s Traditional thinking and Parallel thinking. Illustration created by Gil Dekel.

8.1.1.3 Description

Phenomenology (as discussed by Denscombe, 2003) proved suitable for gaining in-depth access to the processes of creativity in art since it advocates that research focuses on describing things, on how things are, rather than trying to explain them as they happen. In order to understand inspiration, a thing which is sensed intuitively but not known, the researcher needs to learn to observe, accept and describe, rather than try to explain. This approach proved useful to me when I was receiving feedback about my presentations and artworks, as well as when conducting interviews. The first experiment in being ‘open’ to receiving challenging information produced data derived through artistic meditation which was later made into a short film, Interview with authorial-Self (2006/2007; ![]() ). The data was surprising to me as much as it was to those who watched the film (as evident in their feedback), and yet it was not filtered by me but was brought forth as it is (see also revised transcript version of the interview, 2008;

). The data was surprising to me as much as it was to those who watched the film (as evident in their feedback), and yet it was not filtered by me but was brought forth as it is (see also revised transcript version of the interview, 2008; ![]() ).

).

8.1.1.4 Experience

Phenomenology suggests that the researcher should examine events through experiences, and not through predefined theories. Knowledge gained by the senses, and not deduced in the mind, can give clues to such elusive events as the process of capturing inspiration in art activity, since artists describe this process as emotional rather than logical. For example, the poet Anne Stevenson in an interview for this research (![]()

![]() para. 9) argues for ‘connections between you… and your experience, and your feelings… and words… that no analytical psychologist can explain’.

para. 9) argues for ‘connections between you… and your experience, and your feelings… and words… that no analytical psychologist can explain’.

8.1.1.5 Relevant context

Poetry is defined by Robin Skelton (1978: 35), in his classic work Poetic Truth, as an activity that comes to express an experience, not an activity that tries to define or explain. While phenomenology looks at experiences and emotions, it also focuses on the study of the everyday world experience; the study of activities and events which are relevant to the participant in the research, as opposed to other approaches that generalise a theory about events that are remote from the participants. Hence my understanding that the phenomenological approach is suitable for research that focuses on inspiration and yet draws conclusions from ‘down to earth’ events and experiences that matter to participants. This is most important if the research is to advance our knowledge in the study of creative experiences. Otherwise, as my first supervisor challenged me before he accepted this research, I could simply engage in art practice alone outside academia, where I could do and say whatever pleased my creative urge, but which would not give us systematic tools to help us understand creativity.

8.1.1.6 The mundane

By focusing on the things that matter to the participant, the phenomenological approach emphasises the mundane, the simple things that one encounters in one’s daily life. Attention to the mundane is important to this research, which recognises that inspiration occurs in daily life as part of normal activity, and not as a remote meditative experience only available to a few unique people.

8.1.1.7 Identification and objectivity

Instead of applying predefined theories to different people in different cultures or times, phenomenology encourages the researcher to see through the eyes of the participants by suspending their own belief systems as they gather data. Data is collected in all its complexities and depths, even to the extent of recording irrational and contradictory experiences that were observed. If such events happen, then they will be brought forth to the research, because they describe the event or experiences of participants, and not the belief system of the researcher – or, indeed, the literature. However, the data will later be examined in terms of the literature for the purpose of constructing a logical narrative that can shed light on the creative process and be replicable by others. Evaluation and explanations are required if one chooses phenomenology, since events that are known only through the senses and not via the mind tend to lack coherency.

8.1.1.8 Participation

By valuing the way people think, phenomenology sees people’s perspectives and points of view as a topic of interest for research. People are seen as creative beings that have a say and influence on their lives, not as passive respondents. Similarly, I have observed that the creative flow is often enabled by artists who simply seem to take responsibility for their inner urges to create, and thus they create art. While talent can be refined through practice, personal responsibility for the ‘inner call’ must come from the person himself. This was noted in a final art experiment undertaken for this research (see chapter 14), where participants were asked to view themselves as active creators, a perspective which resulted in participants demonstrating a strong sense of access to their inner creative forms of thinking, and acting artistically upon those thoughts.

8.1.1.9 Personality

Other research methods, such as positivism, seek to distance themselves from the so-called personal influences of the researcher. Yet, personal influences and background seem to be the foundation of creative processes in which inspiration transforms from an idea into art. The phenomenological approach accepts subjective experiences as valid data, encouraging the researcher to explore subjective feelings that inspire others as well as those that inspire the researcher himself (an important point in my case, since I am both the researcher and the artist). This touches on the fact that the academic researcher is a person, a human being, and not an objective so-called food-processor that simply receives information and processes it to a desired outcome.

8.1.1.10. First person

For this reason, throughout this thesis I will avoid using the third person form to comment on the research; rather, I will use the first person form ‘I’. I wrote this thesis, and I stand behind it. I am also one of the participants and the observed artists for this research. Clandinin and Connelly (2000: 9) remind us that it is always the ‘I’ who writes the text, and Derrida (Kofman & Kirby, 2002) defines the attempt by classical philosophers and biographers to remove the authors from the writings as ‘pretence’. Derrida suggests the Deconstructionist approach, where text is examined to reveal how the author constructed it and how the reader understands it. Foucault (1988: 115) explains that before we look at a study, we need to understand the role of the author of the work, since behind any study – be it a study in science, art, philosophy, history, literature – stands an author who wrote it. More so, Foucault argues that the bibliography section at the end of a research does not only show the sources from which the author drew, but also the connections and modifications of ideas that the author orchestrated.

In my short performance and film The Prince of Hampshire (2006; ![]() ) I relate to the authenticity of words by saying, ‘…this is why the Egyptians embedded their words in stone’. However, with our modern technology words are not embedded in stones anymore, but rather they are usually composed in electronic forms which are non-tangible and can easily be erased. Words become loose in such non-permanent media, therefore, in this research I shall give the words their ‘birthright’ of association with their author.

) I relate to the authenticity of words by saying, ‘…this is why the Egyptians embedded their words in stone’. However, with our modern technology words are not embedded in stones anymore, but rather they are usually composed in electronic forms which are non-tangible and can easily be erased. Words become loose in such non-permanent media, therefore, in this research I shall give the words their ‘birthright’ of association with their author.

Table of Content: