Inspiration: a functional approach to creative practice.

PhD thesis in Art, Design & Media, by Gil Dekel.

12.2 Space

With a sense of appreciation of the environment, artists allow the observed reality with its beauty to form a part of the artist’s own personality. The experienced reality becomes a space, an inner context of the external environment, which is felt within.

Sound / body / inner space / silence

Wassily Kandinsky made use of his musical training in his paintings. He (1972: 40) asserts that unlike images, sounds do not represent natural phenomena, but rather express what he calls the artist’s soul, and create an ‘autonomous life’ of its own. On the other hand, painting is an act based on a visual object, imitating nature or abstracting forms of nature. Music is ‘an objective language’, as artist Victor Pasmore (Bickers & Wilson, 2007: 352) adds.

However, I do not see Kandinsky’s ‘autonomous life’ of music as something created in the musical composition, but rather expressed through it, as if it were existing there beforehand. Chanting artist Russell Jenkins (![]()

![]() paras. 2, 6) suggests that he has a feeling of the existence of a sound coming from within him, saying, ‘I have a hearing of an Aum…’ and ‘I hear inside’. Jenkins explains that this sound is independent of him to the effect that it is visible: ‘It is like you look at it and you think, ‘Oh, it’s a star that I can pluck out of the sky’’ (para. 2). In that respect, sounds seem to be impressed on the artist and present themselves to the artist. The forms in which sounds present themselves can vary depending on the artist’s skill. In the case of Jenkins, he (para. 4) would aim ‘…to replicate it through [his] voice,’ while Dekel (

paras. 2, 6) suggests that he has a feeling of the existence of a sound coming from within him, saying, ‘I have a hearing of an Aum…’ and ‘I hear inside’. Jenkins explains that this sound is independent of him to the effect that it is visible: ‘It is like you look at it and you think, ‘Oh, it’s a star that I can pluck out of the sky’’ (para. 2). In that respect, sounds seem to be impressed on the artist and present themselves to the artist. The forms in which sounds present themselves can vary depending on the artist’s skill. In the case of Jenkins, he (para. 4) would aim ‘…to replicate it through [his] voice,’ while Dekel (![]()

![]() paras. 34) asserts that sounds come as a guide, advising her on the making of her works.

paras. 34) asserts that sounds come as a guide, advising her on the making of her works.

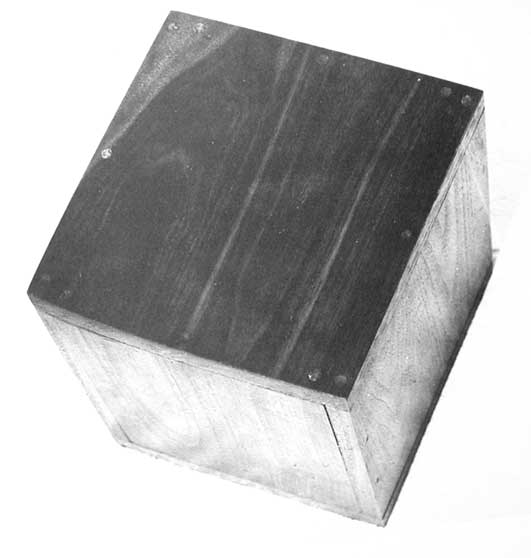

Robert Morris created in 1961 a work whose title is self explanatory: Box With The Sound of Its Own Making (fig. 86). The sound of making the box was recorded on tape which was then played and presented as part of the finished box. Suggesting that the act of making is also the result of the work has shifted sounds in time. The moving of sound in time joins the moving of sound in space, as Warner explains. Warner (2006: 17) says that with the invention of the radio, telephone and television that sound has begun to be displaced in space, as voices were now being moved through the air. I should mention here the use of the Internet to mobile sounds.

Figure 86: Robert Morris, Box With The Sound of Its Own Making (1961, walnut box, speaker, tape recording of the sound of making the box.) Image © the artist/the Morris Studio. Permission to use image obtained from the Morris Studio via the Design and Artists Copyright Society, UK (DACS).

Stevenson adds to the understanding of the impact of sound, approaching it from a cultural historical view: ‘If I couldn’t overhear the rhythms and sounds established by the long, varied tradition of English poetry…’ Stevenson (![]()

![]() para. 15) says, ‘…I would not be able to hear what I myself have to say’. The cultural context of sound, according to Stevenson, enables one to hear oneself.

para. 15) says, ‘…I would not be able to hear what I myself have to say’. The cultural context of sound, according to Stevenson, enables one to hear oneself.

But, I noted that hearing oneself while making art indicates something else than the prevailing notion of hearing one’s own thoughts. Schneider (![]()

![]() para. 9) explains the technique ‘image exploration’ that she uses for writing. Through a semi-meditative technique she seems to have ‘…heard a sound, and it was of my father… I was very shocked because my father was dead’ (para. 10). This inner voice presented itself in a manner that Schneider could not produce at will – the sound of the voice of her father who had passed away years before. Schneider’s description challenges the prevailing assumption that artists ‘imagine things’ that do not truly exist. Even if Schneider did ‘imagine’ this voice, one should ask how did she produce the sound of the voice of her father? It is assumed that when one thinks, that one hears one’s own thoughts in one’s own voice, not in another’s.

para. 9) explains the technique ‘image exploration’ that she uses for writing. Through a semi-meditative technique she seems to have ‘…heard a sound, and it was of my father… I was very shocked because my father was dead’ (para. 10). This inner voice presented itself in a manner that Schneider could not produce at will – the sound of the voice of her father who had passed away years before. Schneider’s description challenges the prevailing assumption that artists ‘imagine things’ that do not truly exist. Even if Schneider did ‘imagine’ this voice, one should ask how did she produce the sound of the voice of her father? It is assumed that when one thinks, that one hears one’s own thoughts in one’s own voice, not in another’s.

Jung describes his own experiments with the inner hearing of voices in a different sound than his. He (1963: 176-177) says that figures would appear in his visions and he would ‘talk to them’. In one of his visions he heard a woman’s voice within him, which asserted that his writing down of his fantasies is an art. If this fantasy was merely fictional then one should wonder how did Jung’s mind produce the sound of a voice of a woman. And if imagining has that ability to re-produce someone else’s voice in our mind, then how can we be assured that the thinking mind does not do the same, producing someone else’s thoughts in our own voice in our mind?

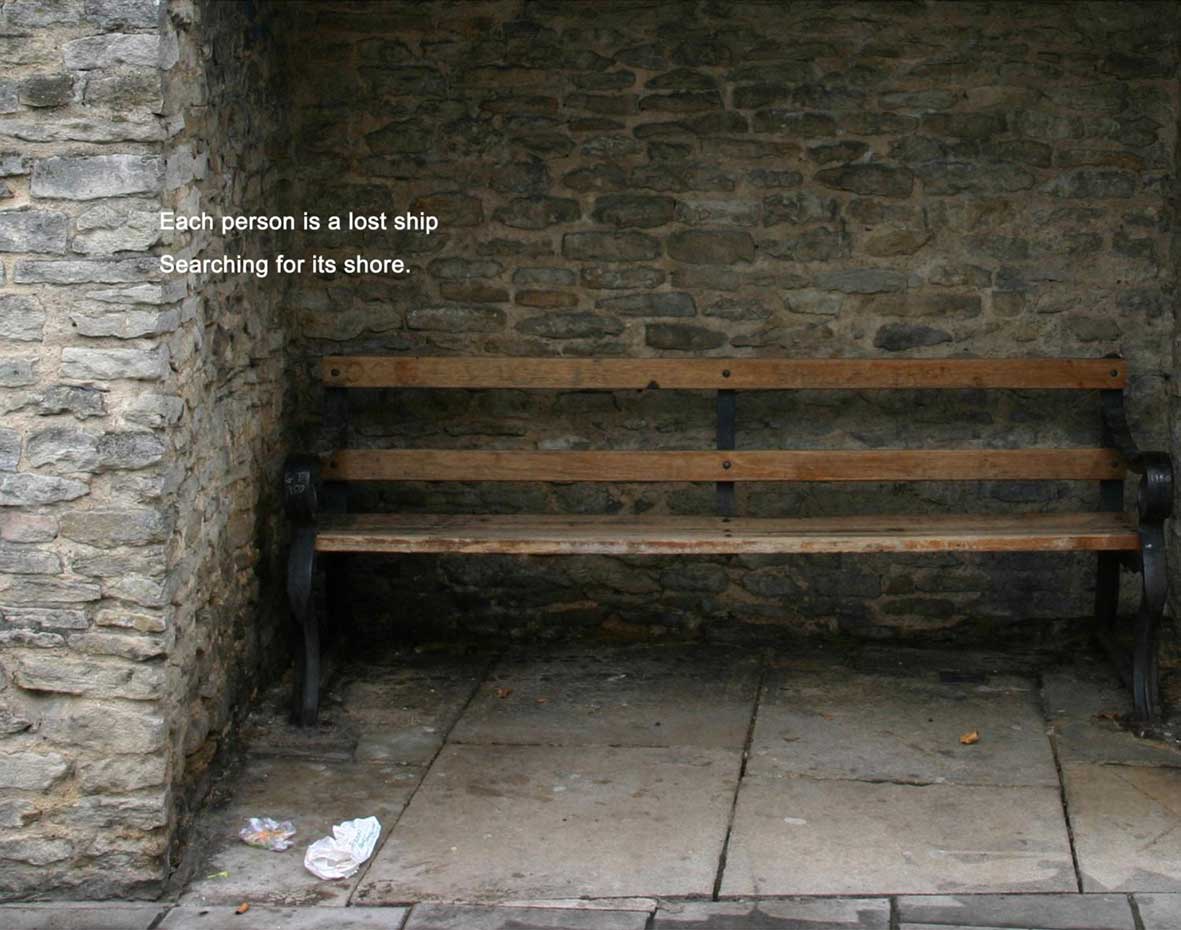

It follows that the sound of one’s own voice may be presented to one by someone else altogether, as I have noted in one of my dreams. Just before waking up one morning, I heard someone calling up my name in my own voice. The calling came from outside of me, as if someone was standing in front of me and calling me, yet it was in my own voice, and so it felt as if that someone was at the same time myself. Dreams seem to allow one to experience what Jung (1963: 45) calls ‘two different persons,’ which inspired one of the images in my photography, poetry and graphic design project Petals of Trust (2007) (fig.87). The most important ‘feedback’ I received on this project was that it was exhibited in Southampton and was bought by a visitor to the exhibition.

Figure 87: Image from Petals of Trust (2007, photography, poetry, graphic design, A3 poster). Image © Gil Dekel.

Artistic experiences of being inspired through words come to artists through different sounds – male, female – which feel as if they are separated from the person, and not created by himself or herself. Wilmer (![]()

![]() para. 42) reminds us that while words are carried out through sounds, that the sound of words ‘…is independent of what they signify’. Sound seems to have a different layer to the words that they carry. Wilmer continues, ‘Of course the sound tends to get associated… with the significance. Nevertheless, the sound is independent.’

para. 42) reminds us that while words are carried out through sounds, that the sound of words ‘…is independent of what they signify’. Sound seems to have a different layer to the words that they carry. Wilmer continues, ‘Of course the sound tends to get associated… with the significance. Nevertheless, the sound is independent.’

In that respect I consider sound as a primal form of expression that is expressed before words or image are realised. Sounds have a direct resonance to emotions, with high sounds corresponding to happy emotions, and low sounds usually corresponding to sad emotions. In the same way that one can feel pressure through touch, one feels emotion through sound. Sound in that respect is the language of the senses which is experienced instead of being read in a written form. It creates events as they are felt rather than perceived logically. Jenkins exemplifies this argument in regards to his inner hearing of sounds and his chanting. He (![]()

![]() para. 7) says:

para. 7) says:

‘…the reason I cannot fully express what I hear is because there is even a higher sound than the one I hear. The original sound is still in a process; it is still being produced. Far from it being a one-off sound that is just created, it is a sound in progress, and it is the creating of everything else out of it. A kind of a source from which sounds are created. And it has not yet been finished being ‘sounded’, so it’s hard to fully re-produce it in chanting.’

I have experimented with the differences that sounds can have on audiences, throughout my films, incorporating different tonalities to express different modes. In Quantum Words (2006; ![]() ) I have incorporated sounds of sea waves, chanting in Hebrew and sounds that represent movements of lights. I have also included subtle singing, which were recorded very close to the microphone. For Confessions of an Angel (2008;

) I have incorporated sounds of sea waves, chanting in Hebrew and sounds that represent movements of lights. I have also included subtle singing, which were recorded very close to the microphone. For Confessions of an Angel (2008; ![]() ) I have recorded the whole narration in an almost whispering sound, again, very close to the microphone, giving the feeling of something ‘very intimate’ and a ‘brevity of the piece,’ to quote from two separate feedback (

) I have recorded the whole narration in an almost whispering sound, again, very close to the microphone, giving the feeling of something ‘very intimate’ and a ‘brevity of the piece,’ to quote from two separate feedback (![]() ). In that way, sound can be seen as an essence that does not only move in space, but rather creates spaces. Intimate sounds seem to provide viewers with a feeling that someone is very near, as if the space of the room, in which they watch the film, becomes smaller. The inner space is altered, becoming flexible in that way.

). In that way, sound can be seen as an essence that does not only move in space, but rather creates spaces. Intimate sounds seem to provide viewers with a feeling that someone is very near, as if the space of the room, in which they watch the film, becomes smaller. The inner space is altered, becoming flexible in that way.

I have explored the notion of inner space in the film A Fallen Angel (2008; ![]() ). For the making of this film I have shared an early experience I had at the age of sixteen. Students from a Playback Theatre took upon themselves to re-enact my story, without any preparation, in front of audiences, as part of the 2nd International Arts in Society Conference, at Kassel University, Germany. By listening to my story and re-enacting it in the room, my inner space felt as if it was internalised within the actors, and then externalised by them in a new form (figs. 88-89).

). For the making of this film I have shared an early experience I had at the age of sixteen. Students from a Playback Theatre took upon themselves to re-enact my story, without any preparation, in front of audiences, as part of the 2nd International Arts in Society Conference, at Kassel University, Germany. By listening to my story and re-enacting it in the room, my inner space felt as if it was internalised within the actors, and then externalised by them in a new form (figs. 88-89).

Figure 88: Still image from A Fallen Angel (2008). Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 89: Still image from A Fallen Angel (2008). Image © Gil Dekel.

I have told my story using these words:

‘I was walking in one of the religious cities in Israel, I am non religion person, amidst these many Jewish religious… I am not religious at all. And then God told me, ‘Here I am!’ in the middle of the street… when I was sixteen. He told me, ‘Here I am,’ so I looked around me and I could not see him. I asked him, ‘Where are you?’ And he told me, ‘You shall write poetry, that is where I shall be’ (from A Fallen Angel, 2008).

And the group performed it, using these words:

‘You begin life, inside this really dark dark tunnel. You are walking, amidst this crowd of all these people. Until you begin to listen just a little bit. You begin focusing on the small words; small words of a higher power. You try so hard, you try to understand what they tell you. Write, write. But who is talking to me now? You have a kind of a scared chill emotion. This, this power, this being has told you to…

You do exactly what you are told. You do what comes from the heart, and you release what’s inside, on this paper.

So you begin to write, you begin to write, until you have this mountain of… It’s Him! You see that being right in front of you.

I see,

I understand,

And I thank you!’ (from A Fallen Angel, 2008).

In a conversation after the performance (24th August 2007) the group explained that they are not just listening to the words that are spoken, but also to the way in which the person ‘carries’ his or her words:

‘I am listening to your words, but really looking to see if you are nervous a bit, thinking, thrilled? These are characteristics and emotions that you don’t realise that you are expressing. They are involuntary, I think that this is what formulates what we take and perform on the stage.’

The effect that the body has in this work seems stronger than the story itself. The actors are relating to the inner space of the person, and then they perform it using their own bodies. This is evident in the explanation given by the group’s director:

‘It is an instinct thing, which we cannot analyse. Acting techniques… particularly in America, where acting methods are used by spending a lot of time analysing your character, doing your substitution work. [However] here you have to take instant decisions based purely on your senses, on your five senses, and whatever that other sense is. So instant empathy has to happen. With your stories, we then tell our own stories and act them, so we can act freely.’

With no preparation before the performance, the five senses and ‘that other sense’ of the actors are reaching to the five senses of the speaker, and not just to what the speaker says. Through empathy the actors are gaining access to the speaker’s inner space. This is an almost automatic-performance, where the actors are guided by the knowledge of their own bodies. That knowledge came from the body of the speaker.

In this experiment I have told the story of a previous experience, and it could be said that the experience was shifted in time, from the past to my memory and to my body and from there to the actors’ bodies. In a way, this project imitates the spontaneity of What is Love? to the extent that the human body reacts instantaneously. My story, as retold by the actors while they performed it, was an expression of the body’s movement, and not its guide. This can be observed in the film where the movements of the actors seem to lead the words that they say, as if movement comes half a second before their speech does.

The notion of inner spaces within the body was explored in a different project that I have created, Waterised Words (2007). For this installation I poured Evian drinking water into three kitchen bowls. Under each bowl I had printed one of the following words: Love, Calmness, or Fear, which could be read by looking into the bowl (fig. 90). I also included the same words on the installation table (fig. 91), and then invited the audience to drink the water with their ‘embedded’ words and to tell me the ‘taste’ of the words (figs. 92-95).

Figure 90: Installation Waterised Words (2007, water, kitchen bowls, printed text, pebble.) Image © Gil Dekel

Figure 91: Installation Waterised Words (2007, water, kitchen bowls, printed text, pebble.) Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 92: Installation Waterised Words (2007, water, kitchen bowls, printed text, pebble.) Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 93: Installation Waterised Words (2007, water, kitchen bowls, printed text, pebble.) Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 94: Installation Waterised Words (2007, water, kitchen bowls, printed text, pebble.) Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 95: Installation Waterised Words (2007, water, kitchen bowls, printed text, pebble.) Image © Gil Dekel.

I chose the words love and fear based on Walsch’s notion that these two are opposites. Walsch (1997: 24) asserts that the opposite of love is not hate, but rather fear. To this I added a third word, calmness, which I considered to have an intermediate value between the other two. In that way I expressed the full spectrum of human emotion, using three words.

The audience were advised that the water is plain Evian drinking water, and there is no ‘trick’ involved intended to fool them. I tested the water in front of the audience to demonstrate this. The purpose of this work was to see how people would respond to the notion of ‘drinking words’; of taking words in, instead of the normal forms of communication where people speak words, i.e. taking words out. In that way I explored what happens to words whilst they are ‘inside’.

I was also attempting to see how can we relate to the ‘obvious’ tools of communication, words in this case, in a challenging way that will tell us something new about ourselves. The idea of attaching a taste to words was meant to leave a physical sensation with the audience, a sensual memory to words, instead of only an intellectual one.

Water was in the bowls in a way that produced stillness, quietness, as if saying nothing. This was in contrary to the spoken or read word in the bowls, underneath the water, which produced sound. In that way I was trying to remove the sound of words, as if to absorb the word’s sound by the water, and focus instead on the sense impression that the experiment produced. Water is a symbol for sustainability as the human body must have water to survive. Words placed within water give the impression of being crucial to one’s existence.

People’s responses were mainly of amusement, with some reporting actually experiencing a different taste to the various waters (although all the water came from the same bottle):

- [tries Fear]: ‘There is an element of earthiness about it’.

- [tries Love]: ‘It is salty I think.’

- [first tries Calmness then tries Fear]: ‘No difference… but I felt calm as I was drinking the Calmness water…’

- ‘Can I mix Love and Fear?’

- ‘Very different taste to all of them. I noticed that the one cancels the taste of the other.’

- ‘Can I have a mix of Calmness and Fear?’

- ‘Did anybody actually want to test Fear?’ / Gil: ‘Yes, they say it is not that bad…would you like to try Fear?’ / ‘No…thank you.’

- [tries Love]: ‘It tastes very clear…’

- [tries Love]: ‘It’s very funny…’

- ‘I know what Fear tastes like… and I know what Love tastes like… Give me some Calmness…’ [tries Calmness]: ‘Flavourless… Quite flavourless. See, I think Calmness is less salty than Fear. It is softer, as if there is round edges on the molecules, as oppose to spiky edges.’

- ‘I find from all this that words are much bigger; they have deeper meanings. Even if one word is a word it has a few meanings to it.’

The purpose of this project was not to gain evidence of ‘deep’ psychological influences, but rather to challenge people, raise questions, and most importantly to give people a tool to better understand themselves. After this project I was approached by a reader from the Psychology school, suggesting we collaborate on a new project where we could test people’s responses through a test group and a questionnaire that he offered to design. While I did like his suggestion, we did not collaborate in the end since my attempt was to indicate, challenge, inspire, and provide tools – and not to test people. I was happy with the challenging element that my work achieved. However, I would love to remake this installation on a larger scale, based on the skills I have gained since to reach more people.

With this work I have represented the notion of an inner voice, which artists report as being so crucial for guiding their creative impulse. My ‘job’ was to visualise this inner voice, through words, forms and colours, and still be reminded that it is an inner one.

For me it is natural to think that artists reporting on an inner voice are given the choice of listening to this voice or ignoring it. If the artist chooses to listen to this voice, he or she is then required to listen to something that is inside and not outside, since that voice is argued to come from within. The artist must exert a sense of silence that allows listening, i.e. drawing oneself’s attention inward. The act of listening is by definition characterised with an inwards drawing, an absorption of sounds from without and to within. Yet, in the case of an inner voice, artists cannot absorb an external voice, but rather have to absorb an internal one. This could be said to be a form of listening where the artist’s ‘inner ears’ listen to a voice that comes from what I shall call a ‘deeper within,’ a place of silence and stillness.

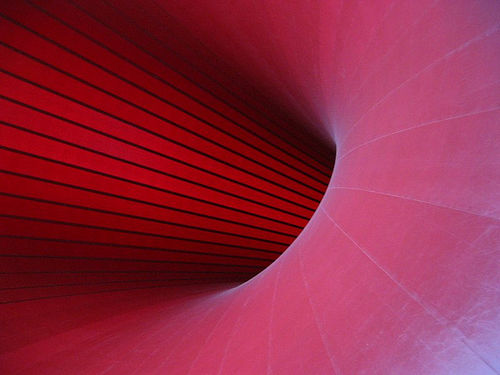

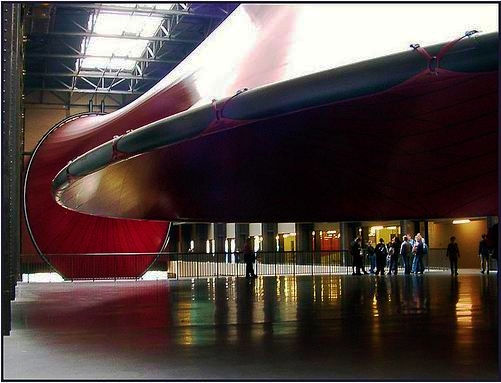

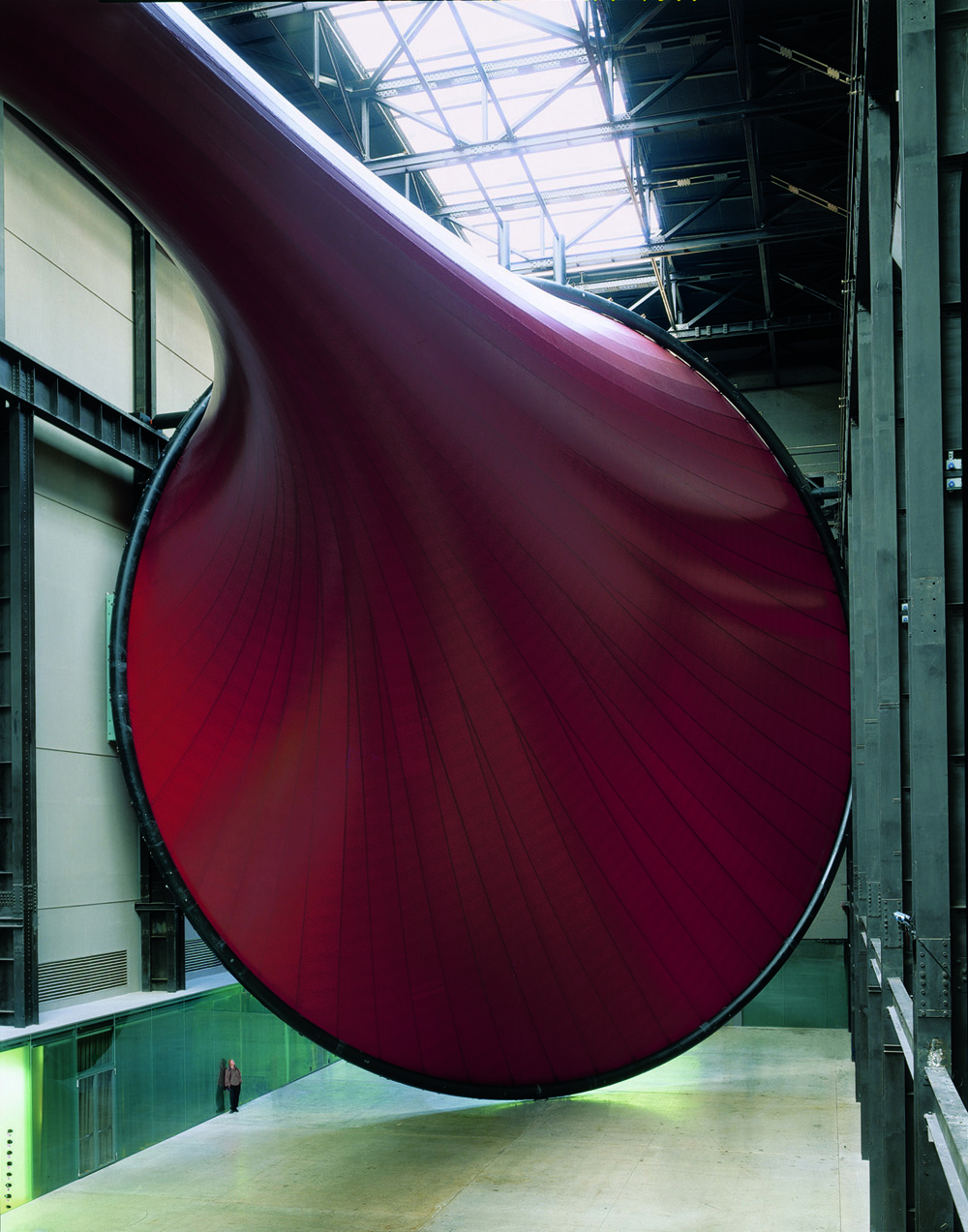

Artist Anish Kapoor (Richards, 2004: 215) describes his momentous works as representing the space within us. Kapoor’s installation work Marsyas (2002; figs. 96-99) at Tate Modern tries to occupy the large space by connecting the space’s three parts with a large PVC membrane tube. The work is described as an exploration of ‘metaphysical polarities: presence and absence, being and non-being…’ (Tate Gallery, The Unilever Series: Anish Kapoor). Following this description I see the work as a symbolic large-scale momentum exploring the duality of sound and silence, with its unique shape resembling large horns or speakers which multiply sounds, as well as large ears which absorb sounds.

Figure 96: Anish Kapoor, Marsyas (2002, PVC and steel installation.) Installation view: Tate, London, 2002-2003. Photo by Flickr’s nahtanoj. Permission to use image obtained from the photographer and Tate Filming Manager, Chris Webster.

Figure 97: Anish Kapoor, Marsyas (2002, PVC and steel installation.) Installation view: Tate, London, 2002-2003. Photo by Norman Craig (Flickr normko). Permission to use image obtained from the photographer and Tate Filming Manager, Chris Webster.

Figure 98: Anish Kapoor, Marsyas (2002, PVC and steel installation.) Installation view: Tate, London, 2002-2003. Photo by Flickr’s nahtanoj. Permission to use image obtained from the photographer and Tate Filming Manager, Chris Webster.

Figure 99: Anish Kapoor, Marsyas (2002, PVC and steel installation.) Installation view: Tate, London, 2002-2003. Photo: John Riddy. Courtesy: Tate. Image supplied by Anish Kapoor Studio. Permission to use image obtained from Anish Kapoor Studio via Lisson Gallery.

Large scale artefacts tend to amaze the viewer due to their size. The image that comes to my mind is of viewers standing at the bottom of this sculpture, raising their heads in silence and in amazement, trying to absorb the grandeur of the sculpture. The vacant area of the Tate gallery’s previous Turbine Hall provides a space where sounds or silence will be multiplied. This can be seen symbolically as representing schools’ national ceremonies or otherwise religious atonement ceremonies where horns are blown, producing loud sounds that stir great awe in the hearts of the spectators. Feelings of awe can be seen for their characteristic element of silence – one keeps silent by standing still and absorbing the loud sound of the horn. Kapoor’s work manages, once again, to deal with metaphysical dualities of sound and silence, where the two are inseparable.

William Blake discusses moments of silence not in the experience of the viewer but rather in the experience of making art. Blake is quoted by Geoffrey Hartman (lecture at The British Academy, London, 3rd October 2007) as saying that he ‘speak[s] silence with my glimmering eyes’. According to Hartman, poets must preserve the belief that all voices are in nature, and are coming ‘out of the silence’. Voices may indicate a form of communication with the artist, or at least a mode where information is transferred through sound and can be received by the artist. This form of communication is expressed by the portraits paintings of Melanie Chan. Chan (![]()

![]() para. 14) asserts that she ‘prefer[s] to be quiet when painting; it is in the silence… that the communion with the flowers can take place’. For Chan the silence is an artistic tool to open up to inspiration, as well as a tool to facilitate a communion with her subject, in what she describes as ‘non-verbal communication’ (para. 28).

para. 14) asserts that she ‘prefer[s] to be quiet when painting; it is in the silence… that the communion with the flowers can take place’. For Chan the silence is an artistic tool to open up to inspiration, as well as a tool to facilitate a communion with her subject, in what she describes as ‘non-verbal communication’ (para. 28).

I would suggest the forms of silence as experienced by artists are different from silence as experienced normally. Artists seem to indicate that silence holds multiple forms of information, sounds as well as colours, as Kandinsky (1972) adds. Kandinsky refers to the silence as an impenetrable wall, which is represented in reality through the colour white. ‘White,’ Kandinsky explains:

‘…has this harmony of silence, which works upon us… like many pauses in music that break temporarily the melody. It is not a dead silence, but one pregnant with possibilities. White has the appeal of the nothingness that is before birth, of the world in the ice age.’

Seeing silence in the colour white, Kandinsky explains that it is ‘pregnant with possibilities… that [are] before birth’. This description fits well with modern quantum physics theories suggesting an observation of space where everything seems to exist at once, before things follow a process of materialisation in which they become visible (Arntz, Chasse & Vicente, 2004: minute 18). It is rather clear why such theories are deemed by many colleagues as ‘poetry’ created by poets and not ‘science’ explored by scientists. Once one attempts to explain what Heidegger (Lemay & Pitts, 1994: 98) calls the mystery of life, the language then becomes poetic. However, Einstein and Infeld (1938: 310) clearly noted in their study of the growth of ideas from early concepts to Relativity and Quanta, that science itself is the creation of the human mind, with the mind’s freely invented ideas and concepts that determine how scientists perceive and interpret reality. If I could contribute to this dialogue I would suggest that science can be seen as the poetry of the mind, while art be seen as the poetry of the heart.

In the film Quantum Words (2006; ![]() ) I have incorporated moments of silence between scenes, where still images with written poems appear with no soundtrack (fig. 100), inspiring the viewer to read the text. While reading, the viewers hear what they read in their mind and in their own voice, as is the case when one reads text. In that way, the external image of silence triggers internal sounds in the viewers’ mind, in what may be called a ‘singing silence’.

) I have incorporated moments of silence between scenes, where still images with written poems appear with no soundtrack (fig. 100), inspiring the viewer to read the text. While reading, the viewers hear what they read in their mind and in their own voice, as is the case when one reads text. In that way, the external image of silence triggers internal sounds in the viewers’ mind, in what may be called a ‘singing silence’.

Figure 100: Still image from the film Quantum Words (2006). Image © Gil Dekel.

A reverse experiment on silence in art was carried out through my film Unfolding Hearts (2006; ![]() ), where the film’s images were interwoven with scenes of poetry that was not written but rather spoken by myself and by the poet Maggie Sawkins. Each poem was cited twice, once by myself (for example, fig. 101) and then again by Sawkins (fig. 102). While Quantum Words generated silence that was completed by the inner sound of the viewer’s thought, Unfolding Hearts worked on generating sound in the film, which seems to generate silence within the viewer and a drifting feeling, as feedback (

), where the film’s images were interwoven with scenes of poetry that was not written but rather spoken by myself and by the poet Maggie Sawkins. Each poem was cited twice, once by myself (for example, fig. 101) and then again by Sawkins (fig. 102). While Quantum Words generated silence that was completed by the inner sound of the viewer’s thought, Unfolding Hearts worked on generating sound in the film, which seems to generate silence within the viewer and a drifting feeling, as feedback (![]() ) suggested: ‘It’s like being hypnotised slightly’; ‘It touches all senses, and relaxes. I have a feeling of falling from a high place on to a carpet of feather…’ It can be argued that the tonality of reading the poems produced the feelings of stillness in the viewers. The visual poetry in a setting of unfolding flowers, followed by quiet voices and a calming soundtrack, offer the viewers with a glimpse into what may be called a collective-silence. Collective-silence is the silence experienced by the viewer together with experiencing glimpses into the artist’s mind, where creative silence operates.

) suggested: ‘It’s like being hypnotised slightly’; ‘It touches all senses, and relaxes. I have a feeling of falling from a high place on to a carpet of feather…’ It can be argued that the tonality of reading the poems produced the feelings of stillness in the viewers. The visual poetry in a setting of unfolding flowers, followed by quiet voices and a calming soundtrack, offer the viewers with a glimpse into what may be called a collective-silence. Collective-silence is the silence experienced by the viewer together with experiencing glimpses into the artist’s mind, where creative silence operates.

Figure 101: Still image from the film Unfolding Hearts (2006). Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 102: Still image from the film Unfolding Hearts (2006). Image © Gil Dekel.

The inner sounds that inspire artists are felt as if they are coming from beyond the capacity of the imagination to produce sounds in the mind. Sounds are felt as a vehicle for an independent source. With these feelings, artists draw inwards into a deeper listening, that transcends the listening to one’s imagination, and reaches a listening to a collective self that is accessed through silence. In this state a two-way form of communication is enabled.

Table of Content: