Inspiration: a functional approach to creative practice.

PhD thesis in Art, Design & Media, by Gil Dekel.

14.3 The workshop experiment

As participants were arriving they all apologised for ‘not being creative’, and suggested that they ‘do not engage much in writing and definitely cannot draw’.

The event started with a short introduction of its purpose, placing it in the context of my PhD research. I presented some formal theories regarding the processes of creativity and the role of inspiration in art making. I then remained in a ‘formal mode’ and discussed my experience of being inspired to create this workshop by an angel:

‘A few days ago I was speaking to my Angel… we had a lovely chat me and my Angel, we were sitting in my room… we had coffee. [And] he told me, ‘You shall make a workshop. You shall invite people, and you shall make an experiment’. An experiment in which we will all draw into our own, what we call, sources of creativity. We will draw inside… through simple steps that I will guide you, and we will see which gifts lie within, because it is not only the ‘external’ where we all meet; it is also the ‘internal’ where we all meet’ (from The Collective Hearts, 2008)

Participant’s facial expressions in response to this ‘formal’ description of communication with an angel indicated that they perceived this as humorous (see fig. 103). Using humour and still being serious regarding what I say, have managed to demonstrate that I am myself open to inner sources of inspiration, without the need to ‘prove’ my opinion to others through a serious argument. The participants’ response to this shows that humour can allow the facilitator to say what he or her experienced and want to communicate, while letting participants to decide if they accept the message or not – without the need to reject anything which may sound different or surprising.

Figure 103: Image from participatory art workshop (still image from film The Collective Hearts, 2008.) Image © Gil Dekel.

By asserting that is it ‘not only the ‘external’ where we all meet; it is also the ‘internal’ where we all meet’, I have raised the idea that by drawing inward we can start to look at the forces of inspiration that call upon us to create.

Bachelard discusses the notion of drawing inward in the context of daily life. He (1969) discusses the intimate corners of the house, as places where people like to curl up and reflect. He sees these intimate corners as symbols to our inner space, which he describes best by using an analogy made by Jung. Jung described the psyche as a building, where the upper story might have been built in the 19th century, and the ground floor in the 16th century. The entrance hall, Jung explains, is reconstructed from the 11th century, and in the cellar we can find Roman foundation walls. Under the cellar there are filled-in caves. Jung sees this image as an analogy to our mental structure, and raises an important point in people’s behaviour. He says that people can hear a noise in the cellar of this house, and hurry to the attic. Once they find no burglars there, they say the noise was pure imagination. Jung suggests instead a method to examine the cellars, and even go further to see on what the cellar stands on, the filled-in caves.

This ‘psyche house’ was a method used by Jung with his clients. Jung would guide his clients to close their eyes, and imagine a downwards-facing staircase. Patients would then imagine going down this staircase and into their inner mental ‘cellars’. Recently, this method was made popular by the author and facilitator Branon Bays (1999), who named it The Journey.

Bays (1999) developed her method following a diagnosis in which she was found to have a football size cancer tumour in her stomach. The doctors had told her that she must be hospitalised immediately and that she had one month to live. Bays refused to accept that direction, saying that there must be another way in which to recover, and asserting that she had a knowing that she would heal. The doctor pointed to her large book library assuring her that there is not even a hint of evidence of someone in her condition being cured. As Bays declined hospitalisation and left the hospital she had a peak-experience where her vision intensified and images became clearer to her, holding a message, or a ‘knowing’, in which she knew that she would heal.

Bays entered strict diets in the following months and meditations where she would visualise going down an imagined staircase to the core of what she saw as the reason for her illness. Bays’s process resulted in a full recovery, and in systemising this method to be used by all people as a way of self empowering.

I have attended one of Bays’ workshops in London, and observed the power of visualisation and spoken words to facilitate conditions in which participants can direct their attention inwards to creative processes that occur inside, and that are usually ignored. Following the use of this method as well as another visualisation method that I studied (Reiki), I managed to experience myself what I can only call depths-of-visions. Depth-of-visions does not refer to observing inner blocks only but also to observing inner insights, as I have experienced, which can teach a person his or her inner powers to be creative. Jung named the depth of vision with the term Archetypes. My interviews with artists demonstrated a sense of creative flows with forms of insights that seem to come from beyond the known way that artists know themselves. I was set to examine these modes of perception in my art workshop.

I asked my participants to close their eyes and imagine a downward-facing staircase. I guided them to slowly descend and focus their attention on a place where they could feel comfortable to observe memories or feelings that could prompt creative imagery (figs. 104-105).

Figure 104: Image from participatory art workshop (still image from film The Collective Hearts, 2008.) Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 105: Image from participatory art workshop (still image from film The Collective Hearts, 2008.) Image © Gil Dekel.

Although I had a pre-written text to read from, I improvised the guidance on the spot, since I had to react to different responses from the participants. Some were ‘faster’ while others were going ‘slower’ in their journey. I was also adapting my voice speed, tonality, and the words spoken to suit all participants, by suggesting two guided ‘tracks’: while I was guiding participants in their ‘journey’ using a slow voice, I was also speaking to those who might be more advanced suggesting through slightly faster voice to start to explore the next step, the inner place, at the same time. Feedback from participants indicated that this approach was needed, as some reflected they had reached the inner place very quickly, whilst others were still descending the imagined staircase.

As I was guiding, I was using gestures as an expression of the spoken story (figs. 106-109). I have watched carefully how actors were expressing words through their body in acting for my film A Fallen Angel (2008; ![]() ), and have used the technique, as the actors suggested themselves, in which they observe how one speaks and how one moves, before they re-enact one’s story. My application of this method is evident in fig. 109, where one participant has raised his hands in front of his face, a gesture which I immediately felt was an important form of bodily expression of my words – and I have re-enacted this gesture at the same time as he did (fig. 109).

), and have used the technique, as the actors suggested themselves, in which they observe how one speaks and how one moves, before they re-enact one’s story. My application of this method is evident in fig. 109, where one participant has raised his hands in front of his face, a gesture which I immediately felt was an important form of bodily expression of my words – and I have re-enacted this gesture at the same time as he did (fig. 109).

Figure 106: Image from participatory art workshop (still image from the film The Collective Hearts, 2008.) Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 107: Image from participatory art workshop (still image from the film The Collective Hearts (2008.) Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 108: Image from participatory art workshop (still image from the film The Collective Hearts, 2008.) Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 109: Image from participatory art workshop (still image from the film The Collective Hearts, 2008.) Image © Gil Dekel.

Once I felt that participants have reached the first step, a ‘place’, and explored it, I then gently guided them back. I asked them to remember their creative place, and then to ‘draw back’ by climbing the imagined stairs, opening their eyes, becoming fully aware of the present, and then writing down or drawing their impressions. I did not attempt to take them further to the second stage, but rather asked that they open their eyes while still aware of the first stage, the ‘place’ they just visited. By having them paint or write, I made sure that they document their impression in case they might forget it later, and also for the purpose of comparing the impression of all their stages later on.

I have departed from Bays’ method in that I asked participants to open their eyes and document their experience, while Bays’ method uses a one-to-one guidance method where participants remain in the inner journey with their eye closed, whilst the facilitator takes the responsibility for writing down the participants’ impressions. I, on the other hand, insisted that participants take full responsibility of their impressions and that they themselves document them. When one writes one’s impression in one’s own words and images, there is no danger that the facilitator interprets and writes them down differently from what they were. The documentation is more authentic once done by participants, and will be easier for them to remember. I also attempted to see how people express themselves creatively (figs. 110-111), remembering my participants’ initial declaration that neither of them can draw nor paint or connect to their inner stages of creativity.

Figure 110: Image from participatory art workshop (still image from film The Collective Hearts, 2008.) Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 111: Image from participatory art workshop (still image from film The Collective Hearts, 2008.) Image © Gil Dekel.

By asking people to remember their inner image while they ‘come back’ to awareness, this have demonstrated that people can hold in their memory or conscious mind the inner image, remember it, and then describe it. This conclusion asserts that inner images, such as images coming in dreams which people tend to forget as they wake up in the morning, do have the capacity to attach themselves to the memory and logic and remain there.

In that way I wanted to examine Jung’s assertion that images are held in the conscious but are repressed by it to the unconscious. My experiment asserts that indeed the conscious mind has the capacity to hold and remember inner images, which people usually associate with the unconscious to the effect that they believe the conscious cannot contain those images. My experiment did not go as far as to prove the act of repressivism, but demonstrated that the conscious mind is indeed much more capable than was thought before.

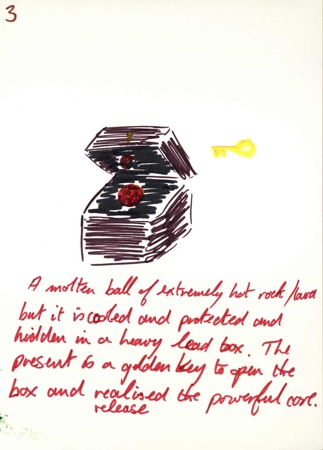

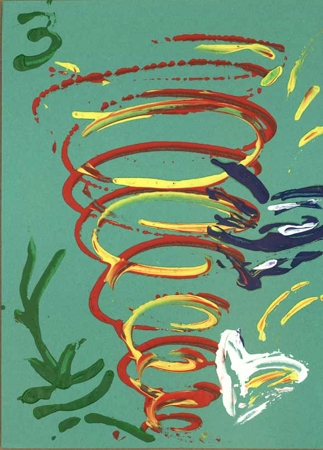

Once participants had finished drawing on paper their impression from the first stage (‘place’), I took them again on the journey, asking them to find the centre of the place – and then come back again and draw it or write it down. Then I took them into the third stage, where I asked them to go ‘inside’ the centre, or beyond it. I have used Bays’ term ‘drop through’ to guide participants to go further, and accept a ‘gift’.

In this third stage, participants went through the place, and the centre of the place, symbolising environment and the individual’s place in the environment. The stage of the ‘gift’ was beyond the individual. I was attempting to find what people can say about the inner call, without me suggesting that there exists an inner call. Five participants simply described the gift that they received, while the other three participants were enthusiastic in revealing that they felt an actual presence of something or someone giving them their gifts.

We then had a group discussion with each participant reflecting on the stages, on what he or she felt, saw or heard, and on their impression of the images and the texts they have created (fig. 112).

Figure 112: Image from participatory art workshop (still image from film The Collective Hearts, 2008.) Image © Gil Dekel.

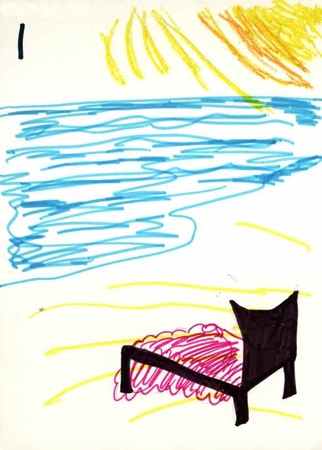

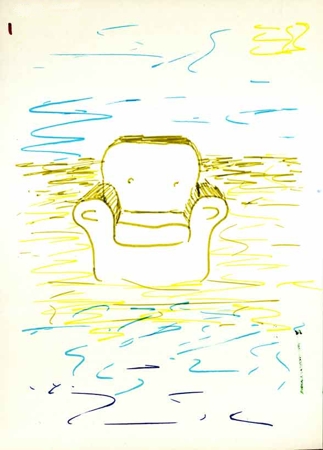

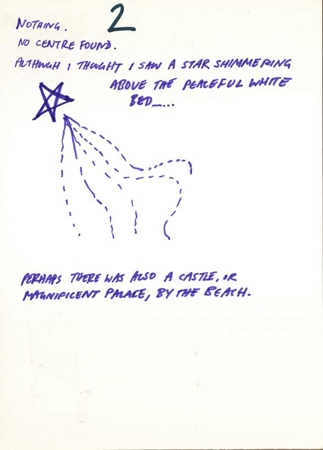

The first stage, a ‘place’ was reported by participants in the form of a room, or a theme of nature. The most commonly theme was a scene on a beach (see two examples from two participants, figs. 113-114). Participants reported:

‘In front of me was this vast ocean, disappears into this really bright sky which was all enveloping. But the ocean is up [at] me, its really calm lapping at my feet.’

Figure 113: A drawing made by a participant in participatory art workshop. Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 114: A drawing made by a participant in participatory art workshop. Image © Gil Dekel.

I noted that participants’ descriptions of their inner visions did not consist only of what they saw, but also of what they felt from the experience of observing the images. The inner image and the feeling around it were united in the descriptions:

‘My daughters… I could feel presence but I could not see them on this beach somewhere… and the left and the right which were just an expansion of this beach. Somebody came with this golden key. That was a key to this red box, to open… I felt really powerful… [inside the box was] a warm strong self… this kind of a collective-identity… almost God, almost [a] spiritual power.’

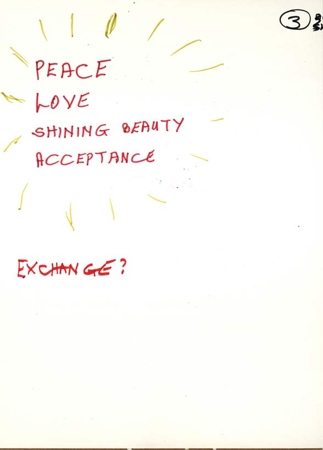

‘A feast of words and colours and perfume. I was absolutely entranced by the perfume of wavelet in spring time. It was just words that came to me, words with halo around them. It was about finding peace, finding love, finding the shining beauty and acceptance.’

‘I go straight to the light… and I feel secure. And I see this landscape in the distance. It’s a sparkly different colours ball; I have never seen anything like it.’

‘And I just thought ‘peace’… it was just my own little bubble in the world.’

‘Very powerful wind and you just enjoy leaning into it.’

All participants used words and imagery (figs. 115-118).

Figure 115: A drawing made by a participant in participatory art workshop. Image © Gil Dekel

Figure 116: A drawing made by a participant in participatory art workshop. Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 117: A drawing made by a participant in participatory art workshop. Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 118: A drawing made by a participant in participatory art workshop. Image © Gil Dekel.

Table of Content: