A modern design of Charlap Family Flag (Design © Gil Dekel)

By Arthur F. Menton

and Dr. Gil Dekel for additional notes {in brackets}, corrections, and images.

Chapter XXIX – The Family of Ze’ev Ben Avraham of Tykocin

Page 483

Rabbi Ze’ev Ben Avraham Charlap and his wife Gittel established their home in Tykocin. Ze’ev was probably older than his brother Moshe who had also been a rabbi in Tykocin. Gittel gave birth to four sons, all of whom rose to be prominent scholars and rabbis. Abraham Gershon, Ephraim Eliezer Zvi Hersh {אפרים אליעזר צבי הירש חרל”פ}, Moshe Aryeh and Yaacov each established themselves in different locations. Their towns became destinations for pilgrims seeking advice, blessings, miracles, or Talmudic interpretation.

Moshe Aryeh lived in Bialystock and later in Trestina. A fragment from Bialystock records gives some information about him.

R’ Moshe Aryeh was a brother of the Mezritch Rebbe, the well-known Gaon and Kabbalist, Rabbi Eliezer Charlap. While in Bialystock, he authored Bar Sheva, a treatise on Chumash and the Megilot. Scholars and rabbis praised him for his zealous devotion to his subject, the clarity of his writing, and for his grammatical style. His books received wide approval. He was also the author of the book Divrei Chofetz, two volumes of homiletics which were collected and published in Warsaw in 5656 [1895-96), and also Dikduk Katan [A Small Grammar] published in Wilna and Grodno in 1833. Later he became the Trestiner Rebbe… Chaim Lublinski’s devoted daughter, who lived in Bialystock, had in her possession a document inherited from her father. It was a list of subscribers to Bar Sheva, along with their comments. The rabbis wrote about Moshe Aryeh, how he was a distinguished scholar, sagacious and well-versed and how it was an honor to be associated with him. The Brisker Rebbe, Rabbi Aryeh Leib Katzenellenbogen, and Rabbi Eliakim Getzel Meir from Shishlowicz referred to him as a “Bialystocker.” In fact, during Shevat of 5590 [1830] he was registered as a member of the brotherhood of the Bialystock Bet Midrash. However, by 5592 he was in Trestina where he was welcomed as a learned rabbi. He was a singular person; a giant of Talmudic scholarship whose death was a serious loss but whose writings on grammar and Tanach will stay with us.[1]

Page 484

A reference to Chaim Lublinski is found further on in the same source. It describes him as “a grandchild of a daughter of the Mezritch Rebbe, a Talmudic gaon and great Kabbalist and holy man, Rabbi [Ephraim] Eliezer Charlap.”[2] Ephraim Eliezer had three daughters but it is unclear which was the grandmother of Chaim Lublinski.

Moshe Aryeh’s and Ephraim Eliezer’s brother, Yaacov, lived in Orlov. He became known as the Konavitscher Rebbe. The origin of this appellation is open to conjecture. Most prominent rabbis have well documented pedigrees, yet our efforts have uncovered nothing of Yaacov’s personal life, his marriage, or descendants. Except for the above reference, the same can be said about Moshe Aryeh. Until new information is exposed, Moshe Aryeh and Yaacov Charlap will remain shadowy figures in the annals of the Charlaps. That is not the case for their brothers Ephraim Eliezer and Abraham Gershon.

Abraham Gershon was born about 1790. He was not yet twenty when he married Elka Rabinowitz and settled in Suchawole. Nine children ensued from this marriage. All reached adulthood, married, and had large families. The oldest was most likely Sarah Freidel who married Israel Moshe Fischel Lapin. Sarah Freidel was the mother of five sons and a daughter, all born in Grodno. In 1862, Israel Moshe Fischel and Sarah Freidel made aliyah. Their names and three of their sons with their wives are recorded in a “List of Bnai Israel of Grodno who settled in the Old City of Jerusalem.” Fischel Lapin is listed as a sixty-six-year-old merchant who “brought with him 60,000 rubies, but his business was not successful. Nevertheless, he was an upstanding citizen.” Son Eliezer, married to Chana Leah, was forty-two and operated a food store. Betzalel and Avraham were leather merchants, married to Tsirel and Esther Chana, respectively.[3] Tsirel’s father was Michel ben Mordecai Rabinowitz. Mordecai had married his cousin Tsipe Henia, sister of Elka Rabinowitz Charlap.[4]

Fischel had been born in Grodno in 1810. He became wealthy as a contractor in the construction of the Grodno railway. He was a religious man and was saddened by the antisemitism of government, church, and people. Fischel was especially affected by the 1840 ritual murder affair in Damascus.

In February of that year, a Capuchin friar and his servant were murdered. The Jews of Damascus were accused of the crime and charged with using the victims’ blood for the baking of Passover matzohs. Many Jews were arrested, tortured, forced into confession and conversion. Others died as martyrs. Sixty-three Jewish children were held as hostages by the authorities. The Western world was shocked by the brutality of the affair, although there were enough events of a similar nature in their own history. Energized by the publicity, Moses Montefiore and French Jewish attorney Adolphe Cremieux led a delegation that secured the release of the captives in August. Under pressure, the Sultan of Turkey issued

Page 485

an edict banning the circulation of blood libels. He was also persuaded to allow European Jews to settle in Eretz Yisrael.

The Damascus trial convinced Israel Moshe Fischel Lapin that if Jews were ever to find freedom and security, they would have to establish their own government in their ancestral home. He was attracted to the writings of Rabbi Yehuda Alkalai of Sarajevo who had proposed the creation of Jewish colonies in the Holy Land as a necessary preparation for the Redemption which would be ushered in by the Messiah. Fischel joined with Alkalai in founding Kol Yisrael Chaverim (All Israel are Friends) and was elected its vice-president. The aim was to encourage and finance land settlement in Eretz Yisrael. Fund appeals were addressed primarily to Jewish notables such as Montefiore and Cremieux

for he knew that his schemes would not succeed without the support of their money and political influence. Alkalai [and Lapin] imagined that it would be possible to buy the Holy Land from the Turks, as in biblical times Abraham had bought the field of Machpela {מכפלה} from Ephron the Hittite… [Their schemes] included the convocation of a Great Assembly, the creation of a national fund for the purchase of land, and the floating of a national loan. Such ideas were to reappear later in Herzl {הרצל} and actually to be realized through the Zionist movement.[5]

In 1862 Fischel realized his dream. He and Sarah Freidel, along with some of their children, went “home” to Israel. The respect and love accorded to this man is evident from the following biographical excerpt:

Rabbi Yisrael Moshe Fischel Lapin emigrated from Grodno to Jerusalem with his family. He was the son of Rabbi Aryeh Leib Hacohen Lapin and lived from 1810 to 1889. Among his sons, who gave him great nachos were Rabbi Betzalel and Rabbi Eliezer.

Rabbi Fischel was an extremely prominent citizen of the Grodno area. Biographers report him as a generous religious man, and he was looked upon as a revered genius of his generation. He was in continuous consultation with such outstanding leaders as Rabbi Yisrael Salanter, Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer, and Sir Moses Montefiore. Rabbi Fischel Lapin became very wealthy as a building contractor and led the construction of the first railroad in Grodno. He was called g’vir {גביר} (superman) in both physique and mind. When such a g’vir emigrated to Eretz Yisrael it was a unique and inspiring event. At that time, Grodno was consumed in commotion and preparation for the farewell ceremonies. A special canopied carriage was prepared to transport the Lapins to the port of Odessa, where they would board the ship which would take them to the Holy Land. The emigration of Reb Fischel was the premier event of the early 1860s for the Grodno community. He had been an outstanding citizen who possessed both wealth of knowledge and worldly goods.

486

He was accorded the title Ha-Naggid, in accordance with traditional Hebraic form.

Reb Fischel was generous in his dispersal of money in Grodno and in Jerusalem, where he fed the poor at his own table. He lavished his benevolence on Torah institutions in Jerusalem. He also established a foundation for the poor which included both a shelter and a kitchen. He was Director of the organization known as Help For the Neglected of Jerusalem. It was established to combat the missionary activities of Christian groups who were exploiting the impoverished conditions of some of the Jews to gain converts. Reb Fischel’s aim was to help the indigent become self-sufficient and thus to regain their self-respect. Young people were trained in trades and professions and the more mature were given help in finding employment. They could then earn a living instead of beg for charity. With their heads held high they would no longer be victims of Christian proselytizing.

Reb Fischel was one of the first Ashkenazi Jews to help Rabbi Yehuda Alkalai in forming Kol Yisrael Chaverim. Formed in 1871, this organization fostered settlement of Eretz Yzsrael. The goal was to build homes and entire villages and to teach the immigrants – arts and culture, as well as trades.

He was one of twenty prominent Jews who formed a company known as Petah Tikvah {פתח תקוה} (Gate of Hope). In 1876 they purchased a huge tract along the Jordan River near Jericho. Reb Fischel invested a fortune establishing agricultural settlements and to help in the rebuilding of Jerusalem. He died in that holy city after giving away all of his wealth. Yet his descendants were successful in their own right.

Reb Fischel was the grandfather of the great Zionist businessmen Betzalel and Leib Jaffe. His own son Betzalel, born in Grodno in 1856, was one of the most respected businessmen in pre-state Israel.[6] In the 1880s he developed public service carriage transportation in Jerusalem. He was also the prime mover behind Chevra Lishikim (a housing company) which built the neighborhood of Shaarei Pinah {שערי פינה}. Betzalel lost a personal fortune in this venture. Moving to Jaffa in 1890, he continued his charitable activities and was a founder of Shaarei Torah (Gates of Torah), a professional and vocational school. Betzalel Lapin was active in fund raising for hospitals and the sick. He was a delegate to the first convention for organizing the settlements of the Yishuv, held in Zichron Yaacov {זכרון יעקוב} in 1913. During World War I, Betzalel was dedicated to helping Jews who were drafted into the Turkish army. Betzalel died in Jerusalem in 1939.[7]

This reference to Betzalel Lapin omits an important interlude in his life. As a young adult he had emigrated to the United States and lived in New York City. Betzalel never felt

487

at home in America. His father had imbued him with a love of Eretz Yisrael and the proto Zionist Lovers of Zion movement had been particularly strong in Suchawole. Suchawole was not far from Suwalk, where Rabbi Shmuel Mohilewer {Samuel Mohilever שמואל מוהליבר} was formulating his program for uniting secular and religious Jews in a thrust for a national homeland in Palestine. Betzalel was spellbound by the charismatic oratory of Mohilewer. The memory of those meetings with young visionaries in Suwalk continued to haunt him in America and he sought out other recently arrived Jews who were sympathetic to the Lovers of Zion movement. By the time he was twenty he had rejoined his family, most of whom were already living in Jerusalem.

Betzalel’s brother, Eliezer Lapin, was a scholar among the activists of Mea Shearim {מאה שערים}. He, too, was a founder of Shaarei Pinah. Eliezer learned Arabic and his proficiency in that language was acclaimed. With R’ Eliezer Zvi Kibunke of Grodno, Eliezer was instrumental in restoring the Mount Zion neighborhood of Jerusalem.[8]

Still another source corroborates the details of the Lapins’ journey to Eretz Yisrael.

In 1862 a family from Suchawole found their way to Israel. Sarah Freidel bat R’ Avraham Gershon Charlap, together with her husband Moshe Fischel Lapin, went to Odessa and from there boarded a ship which brought them to Jaffa in the Holy Land. Sarah Freidel’s grandfather was Rabbi Ze’ev Charlap, Rosh Yeshiva of Tykocin. The sea voyage had been long and difficult. Nevertheless, in Jaffa they hired donkeys and camels and continued on to the Holy City of Jerusalem where they settled. Others from Suchawole followed and before long a community of Suchawole landsleit existed in Jerusalem.

I was in Jerusalem and {in} Moshav Motza one day and had a chance to talk with some of the first immigrants from Suchawole – those who had come in the First Aliyah. There was R’ Yerachmiel Steinberg, still a wonderful old man, and builder with the Lapins of the new Hebrew community of Moshav Motza. His father was Rabbi Herschel Steinberg, son of Avraham Yitzhak the doctor. The grandfather was born in Suchawole and was an expert on the history of the town, relating his knowledge to his son and grandson. They were eager to listen to stories about the people and events that happened years ago. Each day Yerachmiel would visit his grandfather’s house and soak up these stories. They came flooding back upon my visit to him in Moshav Motza… all the people and the life of the town… We felt an immense need to remember, to recall the past of Suchawole, where we were born and were raised. Our home that was, but is no more, the town that

488

was so dear to Suchawole’s children.[9]

We should interject here that the Suchawole Yizkor Book also contains the names of Leibel and Liebe Charlap. When last heard from they were listed as living on Janova Street with their two children.[10]

Shlomo Lapin was another son of Fischel and Sarah Freidel. It is unclear if he ever joined his family in Eretz Yisrael. It is certain that he stayed behind in Grodno when the others made aliyah in 1862. He had an excellent religious education and like his brothers was successful in business.

The nineteenth century was a time of building and expansion in Grodno. In 1869 an orphanage was founded, and it became one of the most solidly built and luxurious structures in the city. R’ Zalman Graditsky was the leader of this institute and was ably assisted by R’ Shlomo Lapin. Other participants were R’ Yechezkiel Ratner and R’ Yehuda Leib Diskin. Slomo Lapin, first-born of “superman” Fischel Lapin, was among the most generous donors to the library. He taught at the orphanage and managed the institute’s affairs, ensuring that everything ran smoothly. His brother, Alexander [Avraham], established the first lithography plant in Grodno. It was known as Lapin Brothers Printing… A Talmud Torah was established in Grodno in 1844, a community charity in 1864, and a hotel in 1888. In 1875 the community set up an organization to provide kosher food to Jewish soldiers. Passover seders were also held for the conscripts whose army camp was just across the river. This latter organization was founded by R’ Lev Zalmanis, son-in-law of R’ Gedaliah Zvi Lapin(er).[11]

Shlomo Lapin was the father of eight sons and four daughters. His daughter, Chana Leah, married her cousin Yaacov Jaffe. Yaacov’s mother was Shlomo’s sister, Chaya Leah; his father was Dov Ber Jaffe. Yaacov’s grandfather was Rabbi Mordecai Gimpel Jaffe of Ruzhany, a leading member of the Hibat Tzion (Lovers of Zion) movement.

Mordecai was born in Utanya, Kowno Guberniya in 1820 and studied at the Volozhin Yeshiva, where he became known for his religious scholarship and mastery of Hebrew and secular subjects. He pleaded the case for Russian Jews with Moses Montefiore, asking him to use his influence with the Russian government. In 1855 he was appointed rabbi in Ruzhany, Grodno Guberniya and served there for over thirty years. During that time he opposed the religious reforms advocated by Moshe Leib Lilienblum and others.

489

Mordecai was a follower of Fischel Lapin and Yehuda Alkalai and became very active in furthering the Zionist settlement movement among the Jews of Russia. He traveled widely through the Pale preaching his message of redemption in the Holy Land and supported Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer’s Hevrat Yishuv Eretz Yisrael (Central Committee for Jewish Colonization in Palestine). He also published many articles in the Hebrew and Yiddish press, most notably in Ha-Lebanon. Mordecai Gimpel, acting on his convictions, made aliyah and helped establish the Jehud colony near Petah Tikvah. He died there in 1891 or 1892.[12]

Mordecai Gimpel’s sister, Batja, married Nahum Kook, grandfather of Abraham Isaac Ha-Kohen Kook. Abraham Isaac Kook was the great rabbi and mystic who emigrated to Palestine in 1904. He was appointed first Ashkenazic Chief Rabbi of Eretz Yisrael in 1921. Rabbi Kook evolved a theory that accepted non-observant Jews as partners in the building of Eretz Yisrael. This concept was anathema among some of the religious, but followed directly in the tradition of Mordecai Gimpel Jaffe and Israel Moshe Fischel Lapin. Rabbi Kook assured his more conservative colleagues that “If being a Zionist [secularist] is to struggle for the upbuilding of the land invested by G-d with holiness, where the gifts of prophecy were bestowed on the Jewish people and divine providence made itself manifest, then it is honorable to be a Zionist.” On the other hand, Rabbi Kook criticized those who reduced Jewish identity to the level of nationalism. To him, the Zionist movement represented the beginning of messianic times; since a material substrate was necessary for the advent of the Messiah, the Land of Israel served that function. “The secular Zionists unwittingly fulfilled G-d’s intention even though they denied the authority of religious tradition.” Abraham Isaac Kook died in 1935 at the age of seventy, but his influence was such that after the Six Day War of 1967, his philosophy was the foundation for the messianic Zionist movement Gush Emunim, which advocated Jewish settlement of the newly acquired territories.[13]

Dov Ber Jaffe and Chaya Leah Lapin had five sons and a daughter. Two of the sons achieved prominence. Betzalel was born in Grodno in 1868 and became a Zionist leader, both in Russia/Poland and in Eretz Yisrael.

He was a key figure in the Zionist movement in the area of his native Grodno. He was a member of Bnai Moshe and established a modern cheder in his home town where, in 1907, he was one of the organizers of the “Grodno Courses” for the training of Hebrew teachers. Betzalel took part in the first Zionist Congresses, was active in the organization of the Zionist movement in Lithuania, and in the publication of Zionist literature in Hebrew, Yiddish, and Russian. In 1909 he went

490

to Eretz Yisrael and, upon the resignation of Meir Dizengoff, was appointed Director of the Geulah Company for land purchase. Under his directorship (1910- 1925), this company was instrumental in extending the area of Tel Aviv and turning it into a city. He was one of the founders of Tel Aviv and a member of the town’s first governing committee. Betzalel was also a member of the Vaad Leumi during its early days (1920-1925). In 1912 he introduced the first modern irrigation into Petah Tikvah, utilizing the waters of the Yarkon River. He was one of the few who fought to safeguard achievements of the Yishuv during its harassment by the Turkish authorities in World War I. After 1918 he was among the organizers of the Yishuv’s Provisional Committee and also served as president of the Jaffa-Tel Aviv community.[14]

Betzalel Jaffe remained active in building the foundations of the Jewish state until his death in 1925. His brother Leib, eight years his junior, was no less active in Zionist affairs. A Zionist leader, writer, and poet, he was born in Grodno in 1876.

He participated in the First Zionist Congress and in those following it and was one of the foremost Zionist propagandists in speeches, discussions, articles, and poems in both Russian and Yiddish. Leib was a member of the Democratic Faction of the Zionist movement and was an opponent of the scheme to settle Jews in Uganda. At the Helsingfors Conference in 1906, he was elected to the Zionist Central Committee in Russia. For a time he edited the Zionist periodicals in Russia, Dos Yidishe Folk and Haolam, in which he published articles on current and Zionist affairs. At the Eighth Zionist Congress of 1907, Jaffe was elected to the Zionist General Council and he directed the regional Zionist Committee for the five provinces of Lithuania. During World War I he was active on behalf of the Jewish Society for the Help of War Refugees (YEKOPO). In 1915 Leib Jaffe was called to Moscow to edit the monthly of the Zionist Organization, Yereyskaya Zhizn. During the brief period of the February Revolution, he was at the center of Zionist propagandist and administrative work. With the consolidation of the Soviet regime, Leib returned to Lithuania, where he was elected President of the Zionist Organization and edited its newspaper, Letste Nayes (later Die Yidishe Tsaytung). In 1920 he went to Eretz Yisrael, where he was elected to the Vaad ha-Zirim (Zionist Commission). He was an editor of the newspaper Haaretz and was editor in-chief from 1920-1921. In 1923 he joined the Keren Hayesod and in 1926 became its co-director. Until his death he traveled widely in all countries of the Diaspora on public relations missions, establishing contacts with intellectual circles. Leib was killed on March 11, 1948, when a mine planted by an Arab terrorist exploded in the courtyard of the Jewish Agency compound. Leib Jaffe’s literary work was devoted to the renascence of the Jewish people and to the love of Eretz Yisrael. He

491

published three collections of Jewish-Zionist literature in Russian and also two Russian anthologies of Hebrew poetry, and a selection of world poetry on Jewish national subjects. His own poetry found its best expression in Russian. In 1892 his first poem appeared in the Russian Jewish Voskhod. His first collection of poems, Gryadushchee (The Future) appeared in Grodno in 1902 and also contains translations of Hebrew poetry. His second collection Ogni na Yysotakh (Fires on the Heights) appeared in Riga in 1936. Leib also wrote poems in Yiddish and in Hebrew. A Yiddish collection, Heymats Klangen was published in 1925. A selection of his articles appeared in Tekufot in 1948. His son Benjamin edited Ketavim, Iggerot ve-Yomanim (1964) and Bi-Shelihut Am (1968; letters and documents 1892- 1948). Leib Jaffe edited Sefer ha-Congress (Book of the First Zionist Congress, 1923).[15]

Israel Betzalel Charlap was a son of Abraham Gershon who, like his sister Sarah Freidel, married into the Lapin family. Israel Betzalel’s wife was Shayna Fruma, daughter of Gershon. She must have been a first cousin to Israel Moshe Fischel whose father is listed as Aryeh Leib Lapin Ha-Cohen. Israel Betzalel and Shayna Fruma settled in Sokolka, a town southwest of Grodno halfway to Bialystock. They had four sons and a daughter. All, with the exception of son Miron, assumed the family name of Lapin. It is unclear why three of the sons would abandon such a distinguished name as Charlap.

Miron, born in 1843, worked as a tanner in Suwalk. His first wife was Rachel, daughter of Abel Margolinski, a rabbi in Baklerowe. Rachel died after giving birth to a daughter, Elka. She was all of twenty-six years. Elka married Shepsel Lewinowski and had a son but little else is known about her. After Rachel’s death, Miron was wed to her sister Henia who was ten years younger than Rachel. Henia bore three sons and four daughters.

Son Abel died in the south of Russia after World War I. Three others, Gershon, Fruma and Sonya, stayed in Europe and were martyred during the Holocaust. Aside from the 1883 birth date for Gershon, nothing else is known about them. Gershon’s twin sister, Chaya Leah, married Ephraim Bacer and had a son, Gedaliah, who drowned in either Kowno or Wilna.

The remaining two children of Miron Charlap emigrated to America. Shayna Raizel became Rose and married Aaron Robinson. Her descendants have not responded to family overtures of friendship. On the other hand, Yerocham Fischel’s family has shown an extraordinary interest in the family history and has attended several reunions.

Yerocham Fischel was born in Suwalk on November 7, 1890, the youngest of

492

Miron Charlap’s children. Fischel was a true son of the Haskalah. He was literate in Russian and German and studied medicine. In 1921 he married Rachel, daughter of Abraham Kaplan and Chana Pesche Rozinofsky and moved to Berlin, Germany. A son, Miron, was born a year later. Rachel was pregnant with her second child when Fischel decided to take the family to America. They landed in New York on January 2, 1924. Their destination was the home of Uncle Louis Bloom of Canton, Ohio. Yerocham Fischel is described as a blue-eyed blonde. Rachel was a tall, fair woman with brown eyes and hair.[16] That April Rachel gave birth to a daughter they called Hannah. Now a widow with four grown children and nine grandchildren, Hannah spoke about her background.

My father was raised in Suwalk. He must have come from an “enlightened” home because he left Poland to enroll in the University of Berlin. He studied medicine there and became a physician. My mother’s family was definitely religious. Her father was a melamed in Suwalk. My maternal grandmother, Chana Pesche (I’m named for her), died when Mom was only seventeen. My grandfather remarried but didn’t have any more children. He died in 1939 on the eve of World War II. The Louis Bloom who sponsored my parents’ entry into America was married to my mother’s aunt, Ida (Chaya). The Blooms had a dry goods store in Canton.

We lived in Pittsburgh until I was three. Then my parents separated and my mother took us to New York City. We lived around St. Mark’s Place. Now they call it the East Village. One summer we went up to Ellenville and stayed there awhile. Returning to New York around 1933 we found a place on the Upper West Side. It was the Depression and my mother had a hard time taking care of us. Even so, she didn’t neglect our Hebrew education. We were enrolled in the school of the Spanish-Portuguese Synagogue on Central Park West. We always had a kosher home, but we spoke English and weren’t overly religious. We only saw my father on occasion, yet I felt close to him. During my teen years I began to gravitate towards a more traditional life style. Religion assumed more importance. My husband to be, Jerry Hurewitz, was brought up in Borough Park and went to Jewish day schools. He had a more religious upbringing. My children are all religious and I am blessed with many beautiful grandchildren.

My brother Myron has also led a successful life. Like our father, he is a medical doctor. Myron is named for our grandfather Miron on the Charlap side. He was born in Berlin, Germany and now lives in Newburgh, New York, with his wife Miriam.[17]

493

The next child of Israel Betzalel Charlap and Shayna Fruma Lapin was Lifsche, born about 1850. In 1873 she married Israel Leib Margolinski, brother of Miron’s wives. A year later their first son Hirsch Wolf was born. He lived a scant three years. Ten years elapsed before Lifsche delivered Elka. Then Chaya Sarah arrived in 1886 and Nathan in 1889. Elka married Baruch Raczkowski and had a son Abrasha who was last seen in France in 1944. We do not know his fate. Chaya Sarah and Nathan emigrated to America, married, and had many descendants.

After Lifsche came Sholem Avram. In 1883 he married Shayna bat Leib Bardin of Sejny, Suwalk Guberniya. Of their four children, three found haven in the New World. Daughter Olga was sent to Siberia and was not heard from again. Her brother Frank and sister Lena lived in the Chicago area. Another brother emigrated to Toronto. All married and had children.

Sholem Avram’s younger brother, Moshe Aryeh, was born in Sokolka in 1863. He came to the United States in the early 1880s and settled in Des Moines, Iowa. Officially, Moshe Aryeh became Morris in America, but he was universally called Kelly. His four children produced a generation which spread throughout the mid and far west and in the process lost much of their Judaic heritage.

Perhaps the oldest of Israel Betzalel’s children was Chlavno, who settled in Chicago where he was known as Charles Lappen. His wife, Florence Sokolow, gave him eight children and the family expanded tremendously in the next generation, spreading throughout the United States.

An unexpected Charlap/Lapin connection was discovered through the wedding of Jennifer Krantz, a great-great-granddaughter of Golda Smolarcyk. The following letter arrived explaining the circumstances:

At a family wedding in Los Angeles last month, I discovered that my cousins of the Krantz family had received an elaborate genealogical tree which included their mother Sarah Krantz. I happen to be related to Sarah through both my mother and father. She and my mother were sisters and she was also a first cousin of my father. …That there is a Ser-Charlap connection is quite startling to me.[18]

I was intrigued that the signature at the bottom of the letter contained the hyphenated name Lapin. The writer may have been related to the Krantz family, but they simply married into the Smolarczyk branch of our family. Thus, Chava Lapin-Reich was not a relative because of her Krantz background. But what about the Lapin side? Conversations with Chava revealed that she is the widow of Shmuel Lapin. Shmuel, named for his paternal grandfather, was the son of Berl and Fanny Lapin.

Before World War I, Berl was a correspondent for a Warsaw based Yiddish newspaper. He was on assignment to South America and was investigating the

494

Jewish community of Santiago, Chile. Berl’s parents had also gone to South America for his sister Marsha was still a young girl when she died in Argentina. Berl’s brother Moshe ran afoul of the repressive Russian authorities and was exiled to Siberia. He escaped and made his way to France. He married and assimilated into French life. Moshe came to the United States after World War I and died around 1921. His son was known as Paul Lappe. For several years we would receive Christmas cards from the Lappes. I don’t know why they thought we’d appreciate them. We are a solid traditional Jewish family. I can’t say we are strictly shomer Shabbos, but we keep a kosher home, we don’t work on Shabbos, and Jewish learning means a great deal to us.

Another sister, Munya, was stranded in Volkovisk by the Great War. There she married Paul Winik and in the early 1920s emigrated to America.

My husband, Shmuel, was one of three children. His sister died of polio in 1928 at age twelve. But Shmuel and his brother Adam inherited their father’s writing ability. Adam worked as a journalist in San Francisco. He was only forty seven when he died in 1961. Shmuel was also a fine writer, well educated in English and literature. He became executive director of YIVO Institute. He was in his early forties when we lost him in 1973. All of Bert’s children died prematurely.

But there are talented progeny in the next generation. Adam’s son and daughter are both writers. It runs in the family. I have three sons. The oldest is a rabbi and educator in Jerusalem. Another teaches Jewish Studies at the University of Maryland and my other son has given me two grandsons, one named Shmuel for my dear husband.[19]

With Chava’s aid, further research turned up additional information. While in Santiago, Berl met a young lady from back home. The records show that on May 21, 1913, Bernardo Lapin Schologovich, a twenty-five year old correspondent, son of Samuel Lapin and Clara [Chaya] Schologovich of Russia, married Fani Charney Jarlip [Charlip], twenty five, daughter of Jaime Charney and Sofia Jarlip, also of Russia.[20]

Chava, her memory jogged by seeing the old marriage certificate, told us that her husband knew of the claim that King David was his direct ancestor. She also remembered that Fanny was born in Minsk Guberniya, probably in the Slonim area, home to so many Charlip/Charlap relatives. Later, Fanny had spent some time in Odessa. In addition, Berl’s family descends from the Grodno Charlaps, through Sarah Fraidel Charlap who became the wife of Israel Moshe Fischel Lapin. Shmuel Lapin, great-grandson of Israel Moshe Fischel, was a miller in the province of Grodno. Unlike many of his family, he did not see settlement in Eretz Yisrael as the answer to the problems of east European Jews. Rather, he

495

was attracted to the ideas of Baron de Hirsch. In 1895 he took his family to an agricultural colony in Argentina. Joshua ben Yaacov Lapin, a grandson of Israel Moshe Fischel, was already director of Baron de Hirsch’s Argentine enterprise. One of the settlements was named Lapinville in his honor. That should have eased the transition, but Shmuel was unable to adapt and the family returned to Grodno. The climate in eastern Europe had changed for the worse. Agitation by the working classes had brought severe responses by the government and, as always, Jews were the special target. The social and economic conditions in Russia were so inhospitable that Shmuel could not re-establish a solid base for his family. Then his wife took ill and died. The children were sent to live with Schologovich relatives in Volkovisk.

By 1902 Berl, barely thirteen, found the insecurity intolerable and left home. He wandered throughout the Pale – between Warsaw and Minsk – finding temporary haven in various communities with Lapin, Jaffe, and Charlap relatives. His sorrow and loneliness was assuaged by a deepening love of nature. He found solace in the beauty of the countryside with its wonderful diversity of wildlife. He expended an inordinate amount of time and energy in learning about the flora and fauna, the sights and sounds of forest and field. A voracious reader, he educated himself and soon found an outlet in composing poetry. At fourteen he contemplated nature, eternal and vast, as a mighty panorama into which he could lose himself and by doing so could achieve serenity and peace. In 1909 he was in Wilna, the Jerusalem of the north. But he longed for a freer world and soon left for the Americas, but not before completing his first collection of lyrics. These paeans to nature, are filled with ecstatic praise, and fervent joy and exultation of youth. Berl is reminiscent of Wordsworth in his veneration of songbirds amid the blossoms. An encyclopedic entry adds to our knowledge of Berl Lapin:

Berl Lapin (1889-1952), Yiddish poet and translator. Born in Grodno, he lived in Argentina 1905-1909 and 1913-1917. In 1909-1913 he lived in the U.S. and settled in New York in 1917. His first lyric collection Umetige Vegen (Sad Ways) was completed in Wilna in 1910 [sic], where he had come under the influence of Chaim Zhitlowsky and the literary group Die Yunge. His excellence as stylist is reflected in his translations of Shakespeare’s Sonnets, Russian lyrics, and American poems, and his collected poems Der Fuler Krug (The Full Pitcher), 1950.[21]

Die Yunge was a Yiddish literary movement which burst on the American scene in 1907 and captivated readers, critics, scholars, and the general public until after the conclusion of the Great War. The group was made up of Russian immigrants who had witnessed the failure of socialist uprisings against the tsarist regime. Many had relatives who had been victims of vicious pogroms and they dreamed of living under Western democracies where art and literature could flourish, and writers were unfettered from strictures of a coercive government. They were children of the Haskalah {השכלה} and the old traditions held little

496

sway over them.

These talented young writers sought to emancipate Yiddish literature from lachrymose sentimentalism and from propaganda for social purposes. They abhorred the moralizing tone which still persisted from the days of the badchonim and maskilim. They remained aloof from the tide of Jewish nationalism, on the one hand, and political cosmopolitanism, on the other hand. They saw in art primarily the expression of an individual’s mood and unique sensitivity. They accepted the slogan of art for art’s sake. They de-emphasized content. They strained for perfection of form. They used the word and the word-combination not to elucidate concepts or to clarify problems but rather to communicate impressions and to satiate eye and ear with images and tonal effects. They wanted to lead the Yiddish muse out of its parochial hamlet and onto the world scene. They tried to raise the dignity of the Jewish vernacular to the level of English, German, and Russian. They insisted on grafting on to Yiddish the newest innovations of occidental literary theory and practice. They produced original works of merit and impeccable translations of foreign poetry. They enriched the Yiddish vocabulary with resplendent, beautiful sounding neologisms.[22]

Die Yunge was a self-imposed name. It was meant to convey youth, courage, dynamism, and progress. The group proclaimed that “only new writing was worth reading and only new values worth considering.”[23] At first, such statements were met with derision but as the group expanded and their work reached a wider audience, they commanded more and more respect. Berl Lapin’s arrival in New York added to Die Yunge’s prestige. The following passage gives a definitive review of his contributions:

Lapin’s contributions lie more in the refinement of Yiddish verse than in the introduction of new subject matter. He seeks quiet effects. He was most meticulous in his choice of language. He did not let words flourish as weeds in his poetic garden. He rather wooed each word until he extracted from it essential meaning, music, image. His ideal was clarity and not labyrinthian profundity …

Lapin’s mastery of form enabled him to enrich Yiddish poetry with impeccable translations of Shakespeare’s sonnets, Russian lyrics, and American hymns. To read or sing “The Star Spangled Banner,” in Lapin’s translation fills one with astonishment at the flexibility of the Yiddish verse even when it is fettered by a foreign model and a prescribed melody. His beautiful renderings of Robert Frost, A.E. Housman, Edwin Arlington Robinson, and Edna St. Vincent Millay proved

497

to Yiddish readers that the subtlest nuances of modern poetry could be effectively reproduced in this revitalized tongue.

To his selected poems, published two years before his death, Lapin gave the symbolic title Der Fuler Krug (The Full Pitcher). The poet was the resonant pitcher that gathered up and poured out in a flow of verbal rhythms the joys and pains of all animate and inanimate objects that crossed his path from man and beast and bird and plant and rock and cloud. His songs of New York reproduced the roar of its cavernous streets, the jungle noises of its subterranean heart, the siren wails of its piers and ferries, the tramping of its hastening multitudes on its stony pavements. But Lapin also perceived the individual in the crowd, the uniqueness in each member of the so-called masses. When a “hand” died in the shop and was replaced, unmourned and immediately, by another “hand”, he, the poet, called upon the machines and tools to mourn the departed hand, for it was attached to a human being and with it also perished a good heart and a kind intelligence.

Lapin’s ultra-sensitive social consciousness led him to reject pure aestheticism as a way of life. But he did learn from Die Yunge not to let his social poetry degenerate into metrical propaganda but rather to clothe his social sympathy in well-proportioned, well-balanced, well-disciplined form.[24]

Chava had mentioned that Berl’s sister, Munya, had been wed in Volkovisk. She had been living with Schologovich relatives but her father, Shmuel, had kin who had been in Volkovisk for some time. One of these was Israel Lapin, an observant man and a follower of the religious Zionism espoused by his grandfather, Israel Moshe Fischel Lapin. Like so many of the Grodno Lapins, Israel sought his fortune in building and real estate. He married Rivka Collier and the path of their lives took many strange turns as described in the following newspaper announcement:

THE SAGA OF THE RE-INTERMENT IN ISRAEL of ISRAEL and REBECCA LAPIN

Israel and Rebecca Lapin were reinterred on November 8, 1976, on the Mount of Olives, Jerusalem. Their bodies were brought from Salem, Massachusetts, United States. Delegations from the Etz Chaim Yeshiva and the Lubavitch Yeshiva took part in the ceremony. The couple’s wish to be buried in Israel has now been fulfilled – after fifty-seven years in the case of Israel Lapin (who died on September 18, 1919) and fifty-one years for his wife, Rebecca (who died on April 14, 1925). Israel and Rebecca (nee Collier) Lapin came to Israel with their three children, two sons, John and Jacob, and daughter, Fannie, in 1885, as young religious pioneers from Volkovisk, Tsarist Russia.

After living for several years in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City of

498

Jerusalem, they moved out to help form and build the community of Mea Shearim {מאה שערים}, Jerusalem. Israel Lapin was a successful builder and realtor. Several of his buildings still stand and are in use in Mea Shearim. Mr. Lapin was affectionately known as “Der Neier Barron.” His sons attended the Etz Chaim Yeshiva.

As a result of restrictions imposed by Turkish law, Mr. Lapin fell on difficult financial times. In 1903, he left with his family for the United States, eventually settling in Salem, Massachusetts. In Salem, he recovered his fortune as a successful builder and realtor. He and his wife planned to return to the Holy Land in 1914, but were prevented from doing so by the outbreak of World War I. In 1919, at the age of sixty-five, while en route for Palestine, he died of a heart attack at the Salem railway station, and was buried in Salem.

His daughter, Fannie Lapin Glovsky, returned to Palestine with her husband, Samuel, in 1936. In 1939, they purchased grave sites on the Mount of Olives for the reinterment of her parents. Then came World War II and its aftermath, and then the nineteen year Jordanian occupation of Judea, which prevented the reinterment. Mrs. Fannie Lapin Glovsky died in Israel in December 1952. And now, finally, the grandchildren and great-grandchildren have made arrangements to bring Israel and Rebecca Lapin to their eternal rest on the Mount of Olives.[25]

We note from the above that Israel Lapin was one of the builders of Mea Shearim. At the same time, Rabbi Dov Ber Abramowitz was an executor of the Mea Shearim community. Dov Ber, grandfather of Abram Leon Sachar, was husband to Miriam Charlap. Israel Lapin and Dov Ber, both concerned with rabbinic yichus, certainly must have been aware of their common family connections. The announcement goes on to give a complete listing of the grandchildren, great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren of Israel and Rebecca Lapin “who are prominent members of the Jewish community in the United States and Israel.”[26]

We turn now to David Shlomo, son of Abraham Gershon Charlap, who raised three sons and two daughters. We know a little of Avraham, Moshe Aharon, and Elka. Avraham married a girl from the Scheinholz family and settled in Sejny, Suwalk Guberniya. His son, Ephraim, was a seventeen year old student when, together with his cousin Moritz ben Elias Scheinholz, he left Sejny for America. The boys traveled to Bremen where they boarded the SS Friedrich der Grosse on July 3, 1909. They were greeted by Moritz’s sister, Lily Berguson [spelling unclear] who was living on Greenwich Street in New York City.[27] We

499

do not know what became of Ephraim after that.

Elka bat David Shlomo married into the Shereshevsky family. This family is descended from the famed Shershaver Rabbi, the father-in-law of Yehuda Leib ben Abraham Charlap. Elka had six children. It is believed that she and her children emigrated to America. We are uncertain about her husband. One son was Hersh Zvi Aryeh Shereshevsky, born in Grodno. In America he became known as Harry. His wife, Ida, gave birth to their only child, Phyllis, in Patterson, New Jersey. Harry then moved to Elmira, New York, where he was a silk manufacturer.[28]

David Shlomo’s son, Moshe Aharon, was born in Grodno about 1865. He owned a well-known hotel and operated a large cigarette factory in conjunction with his in-laws. An adjunct business was the manufacture of matchbooks. Which leads us to an interesting anecdote associated with the accession to the throne of Tsar Nicholas II.

Nicholas II was crowned in 1894 and immediately promised to continue the repressive policies of his predecessor. In January of 1895 he proclaimed, “The principle of autocracy will be maintained by me as firmly and unswervingly as by my late lamented father.”[29] Despite such assertions some Jews vainly hoped for a respite in the persecution. They pointed to the inclusion of three rabbis at the coronation ceremonies in St. Petersburg. Encouraged by this sign, the St. Petersburg Jewish community “reciprocated by commissioning Mark Antokolsky to produce a silver angel handing the crown to the new tsar and presented it to Nicholas.”[30]

In the same spirit, Moshe Aharon Charlap attempted to curry favor with the new regime. At great expense, he produced thousands of matchbooks with the portrait of Nicholas on the cover. He distributed them widely and expected the administration’s approval for his respectful gesture. The response was quite the opposite. Government agents raided his factory and arrested the hapless Moshe Aharon. The charge was subversion and disrespect of the royal authority. Paranoid tsarist advisers had determined that the matchbooks were produced so that each time a match was struck the face of Nicholas II would receive a blow. They saw this as a purposeful act of sedition. Moshe Aharon endured severe harassment from the “justice” system before being freed.[31]

Shortly thereafter, Mose Aharon married Minna Shereshevsky who was probably the sister of Elka’s husband. In 1900 Minna gave birth to a daughter, Sonia, and a son, Hesse. Seven years later, she presented her husband with another son named Zvi. In the mid-1920s Zvi was living at 60 Rue de Moulin in Liege, Belgium, with a cousin listed as Leon Charlaja [sic]. This is almost certainly a misprinting of Charlap or Charlak, but we have not

500

identified how Leon fits in the family. Zvi, then known as Grygor, was a student at the university. After completing his studies in 1926 he came to America on a student’s visa. The records show that he arrived at Ellis Island on March 26 aboard the SS Berengaria from Southampton. The blonde, blue-eyed Grygor was planning to study for three years at Columbia University. He was to live with his aunt, Ella Sherin at 195 Governor Street, Patterson, New Jersey.[32] This was surely Elka. The Shereshevsky family had Anglicized their name to Sherin or Sheron. Grygor became Gregory, completed his MBA degree at Columbia, and then decided to study law. He enrolled in the University of Montreal, probably because he was fluent in French, but also studied at McGill University. He received his law degree and married Edith Nobleman. Gregory was “very active in all Jewish and civic affairs.” He supported two congregations, served as president of Canadian ORT, was a patron of the YM/YWHA, and was recipient of the Silver Certificate for twenty-five years of service to Bnai Brith.[33] Gregory’s sons, attorney Monroe and packaging entrepreneur Harvey, continue to live in Montreal. Both are married with children.

Harvey told us that his father sponsored the migration to Canada of Hesse and Sonia. Uncle Hesse settled in Montreal where he manufactured frames for handbags. His son, Carl, was an architect. Sonia’s first husband was a man named Metek. They moved to New York but her son George, a mining engineer, returned to Canada and lives in Toronto. He reassumed the Charlap name. All of the grandchildren of Moshe Aharon Charlap and Minna Shereshevsky married and there are now seven great-grandchildren. Harvey also mentioned that a large group of Shereshevsky cousins live in the Boston area and are known as Sheron. He remembers his father speaking of an Aunt Gittel who came to Montreal after surviving the Holocaust, but he does not know where she fits on our tree.[34]

One of the Shereshevsky cousins became Sonia’s second husband. Jacques Sherry was born in Grodno in 1899 to Yitzhak Shereshevsky and Rachel Makover. His parents worked with Moshe Aharon Charlap in the tobacco business. The Y. Shereshevsky factory was one of the major manufacturing businesses in Grodno. It was said to employ 2,000 people, almost all Jews. This was approximately ten percent of the entire Jewish population. Given the large number of children in Jewish families, Shereshevsky Tobacco touched nearly every Jewish family in Grodno. The Shereshevsky/Charlap management recognized their responsibilities to the Jewish community. “Work stopped on the Sabbath and Jewish festivals and it maintained a school for the children of the employees.”[35] Upon the advent of Polish independence after World War I, governmental authorities looked at the Y.

501

Shereshevsky Tobacco Company with rapacious jealousy. By 1920 it was nationalized and the majority of Jewish workers were forced to leave.

When the government, a number of years ago, decided to convert the tobacco business into a national monopoly, several thousand Jews were thrown out of business; but Jews were allowed to continue to sell the tobacco made by the government. In 1937, however, the government declined to renew their licenses for this purpose, and it is estimated that 30,000 Jews lost their livelihood.[36]

It was too much for Yitzhak and he mercifully passed away in that year of 1937. His wife lived to witness the horrors of the Nazi invasion. She was deported to Treblinka and was never heard from again.

Jacques had worked for ORT in Ruzhany and Grodno. He also served as president of the Chalutzim {חלוצים} organization in Grodno. He left Grodno for St. Petersburg and then surfaced in Vienna where he operated a travel agency. He married in Vienna in 1930 and had at least one son. His wife may have been a victim of the Holocaust. He and Sonia married after the war and eventually settled in Tucson, Arizona. “While in Europe Sonia wrote a book proving that the Electric Company of Warsaw was German owned rather than French. After that she was on the German black list.” Sonia died in 1984.[37]

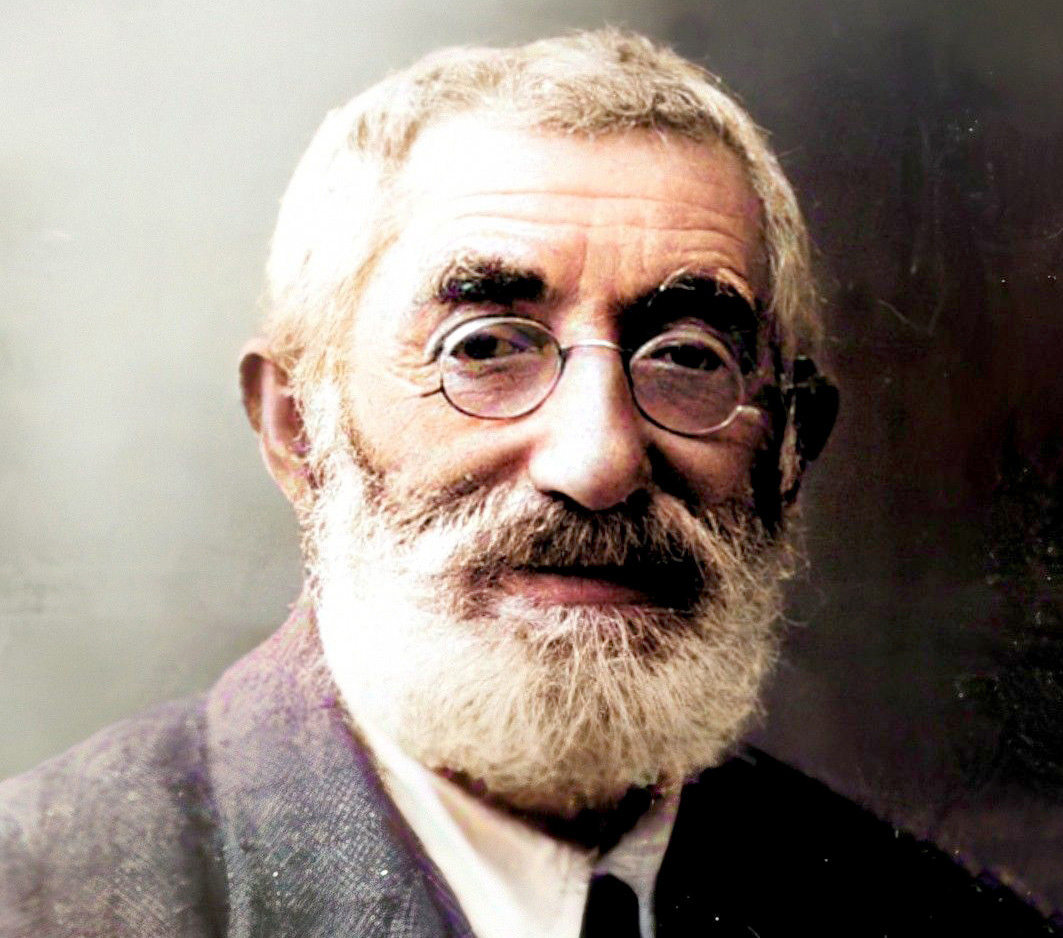

The most renowned of Ze’ev Charlap’s accomplished sons was Ephraim Eliezer Zvi Hersh {הרב אפרים אליעזר צבי הירש חרל”פ, הגאון ממזריטש} . He was most likely born in Tykocin somewhere between 1780 and 1793. He displayed unusual scholarship and creative thinking at a very early age. By the time he was twenty, his reputation was already reaching outlying shtetls. In 1826 he was invited to assume the post of Rabbi of Szczuczyn, a town some thirty miles northwest of Tykocin. His wife of several years, Sarah daughter of Yehuda and Chana, had already presented him with three sons, Ze’ev Wolf, Yisrael, and Yitzhak Yehezkiel. While in Szczuczyn, four more children were born, Rivka, Yente, Chana Dinah, and Yosef Shlomo. He also served as rabbi in Goniadz, Biezun, and Sochaczew.[38]

Rabbi Ephraim Eliezer Zvi Hersh (Hirsh) Charlap “Gaon” tzadik of Mezritcher. Author of book ‘Hod Tehilah’ 1899. הרב אפרים אליעזר צבי הירש חרל”פ, הגאון ממזריטש. Tykocin. Szczuczyn. Miedzyrzec Międzyrzec Podlaski מזריץ’ (מזריטש) פודלסקי. Mezritcher Rebbe. Art copyright © Gil Dekel.

By 1834 Ephraim Eliezer’s fame as a tzadik and wise man had spread throughout eastern Poland. In that year he became rabbi in Miedzyrzec {Międzyrzec Podlaski מזריץ’ (מזריטש) פודלסקי.} He was belovedly referred to as the Mezritcher Rebbe or even more often by the respectful title Gaon of Mezritch. He surrounded himself with an expansive library and it seemed that Sarah was always preparing for visiting rabbis and scholars who had traveled vast distances to confer with her husband. Despite the anti-semitism and political repression, Ephraim Eliezer’s outlook on life was very positive. He was repeatedly asked to preach his message of confidence to gatherings of Jews. Then in May of 1844 Sarah died at the age of fifty-nine. Ephraim was bereft without his life-long companion. He could not tolerate the

502

loneliness. As soon as the thirty day mourning period had elapsed, he took a second wife, forty year-old widow Hinda Dyment. Then a fire consumed his treasured library and destroyed his spirit. Within five years, on August 1, 1849, the Gaon of Mezritch passed away. His writings include Ateret Zvi (Crown of Zvi), Raoch Nichoach (Pleasant Breaths), Hod Tehilah (Glorious Song of Praise), and Sefer Migdanot Eliezer (Book of the Sweets of Eliezer).[39] The latter is his most widely distributed book. An 1895 edition has the following introductory approbation:

These precious sweet sayings that I am putting before you today came from the lips of the famous tzadik – words that soar with the wide wings of a great eagle, infused with the true genius of accepted G-dliness – the famous tzadik, Ephraim Eliezer Zvi Charlap. He served in a few of our sacred communities and is resting in peace in Mezritch. He preached a great deal and was a profound philosopher of Talmud, Gemara, Midrash, and Halacha. He passed judgment in decisions laced with golden thoughts. After him, the bright light of his views shine over the “orchard” of our lives. His oratory rings in the twelve speeches presented here; speeches filled with his depth of intellect and which were very pleasing to the ear. All of these I collected from manuscripts that were left by him and my spirit was moved to bring them to light for you to read.[40]

The first publication of Sefer Migdanot Eliezer occurred posthumously. Eliezer’s family and admirers arranged that a collection of his writings, rescued from the disastrous fire be edited and formally published for the benefit of future generations. Among these admirers were the Gaon Rav of Kotsk, Yitzhak HaCohen Feigenbaum, Mordecai Chaim Leib Schweib, Moshe Katzenellenbogen, and Yaacov Shapiro. They looked upon Ephraim Eliezer Zvi Charlap as a holy tzadik, whose insights into Kaballah and Torah shown with a brilliance that rarely appears.

This book [Sefer Mignadot Eliezer] honors the memory of that great Torah sage, whose genius in Kaballah was reflected in his commentaries. His keeness of mind was above all others and he bestowed his advice upon with generosity and compassion. He was the son of generations of famous scholars in a family that was centered in Tykocin. All of his brothers became famous rabbis. Rabbi Ephraim Eliezer Zvi was more than a genius; he was a noble saint, a person of G-d whose mysteries of the secret books were upon his tongue. He served in several communities and until 1849 was head of the Bet Din in Mezritch. He left us many books, commentaries, and explanations written over a period of fifty years. Many were

503

damaged by fire, water, and insects. So now I have decided to copy some of these that were given to me by his elder son, Ze’ev Wolf, in Eretz Yisrael, after arriving from Poland. Ze’ev Wolf died soon thereafter. Because there was no order to these documents and the letters were very old, I arranged everything like a rose, copying portions of the Lord’s slave Eliezer, as though they were petals of the flower. His later writings were also about Torah and in addition to his commentaries, there was a small notebook containing twelve eulogies which had been given to his old and dear friend Mordecai Schweib.[41]

Even though Ephraim Eliezer Zvi Hersh Charlap achieved great fame, little is known about most of his children. Ze’ev Wolf married, had at least one son, and made aliyah. He lived in Jerusalem. Chana Dinah married on January 19, 1852 at the age of twenty-two. Her husband was Zyskind Rosenbaum, son of Yosef and Frume of Siedlce. Nothing is known of Yisrael, Rivka, or Yente.

Yosef Shlomo ben Ephraim Eliezer Charlap was born between 1830 and 1832 in Szczuczyn. He was married twice but had children only with Shayna Etka from Warsaw. There were four or five sons and a daughter. Nothing is known of the daughter. The sons were Ephraim Zvi {one of the founders of the city Rehovot, Israel אפריים צבי, ממיסדי העיר רחובות}, Moshe, “Shlomo” (probably Shmuel), Shmerel {Sigmund שמריה (שמרל) זיגמונד}, and another listed as Leyzor Hirsch. The last named was born in Miedzyrzec in 1852. He might be the same person as Ephraim Zvi whose birth year was between 1852 and 1858.

Other than his birth in 1859, Moshe’s early life remains a mystery. The evidence indicates that, like many other Tiktiner Charlaps, he went east to the area of Novogrudok or Slonim. There he married and had several children. At least one son and one daughter of Moshe stayed in what became the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. We have not found any mention of them or their progeny. However, another son, Zvi Hirsch Harlap {not to be confused with his uncle, Ephraim Zvi}, emigrated to Israel in 1920 at the age of eighteen.

Zvi Hirsch was among those pioneers who came to Palestine in what has become known as the Fourth Aliyah {העלייה הרביעית}. He and his companions were members of Hechalutz {החלוץ}, the organization which had prepared a whole generation of diaspora Jews for the physically demanding task of building a Jewish nation in Eretz Yisrael. The idea for this organization had roots in the old BILU {בילו} movement that was associated with the Lovers of Zion. But its new incarnation had been proposed by Joseph Trumpeldor {יוסף טרומפלדור} around 1908. He believed that young Zionists should be trained in their countries of origin for the trying new life in Palestine. In the wake of World War I, the Hechalutz movement gained strength in Russia and before its suppression by the Soviet regime, had supplied Jewish Palestine with a generation of devoted workers. They were idealistic in their goals and Spartan in their dedication. They had to prove that the Jewish nation could produce tough men and women who could, through self-denial and sheer will, master the challenge of any manual task.

504

Zvi Hirsch Harlap, the scion of a scholarly rabbinic family, became the archetypal chalutz. He worked in agriculture and construction and endured harsh, primitive conditions to achieve his goal of helping to build the new Israel. Zvi Hirsch also did his part in the defense of the recently attained gains. Early in 1920, the year he had arrived, marauding Arabs had attacked four villages in the upper Galilee. At one, Tel Hai, the hero Trumpeldor had been killed. Jews across the political spectrum were energized to form self-defense organizations. Block houses and watchtowers were erected, barbed wire strung, and defense posts manned to protect settlements from attack. Zvi Hirsch served in a group known as the Border Cavalry. These pioneers were responsible, not only for guarding the settlements, but also the fields and herds of livestock.

There was no night grazing without armed guards. A troop of horsemen and a posse on foot, armed cap-a-pied, spread out in the valley, their ears cocked to every rustle and quiver; eyes piercing the darkness to detect the least shadow; sure hands on the butt ready at any moment to greet uninvited guests. Guarding the herds was more difficult and dangerous than guarding the settlement.[42]

Mania Schweitzer had also made aliyah in 1920. She was a fifteen year-old girl from Kamenetz-Podolsk. She and Zvi Hirsch were wed within a few years and in 1926 their son Amiram was born. Amiram studied architecture at the Technion and then received an M.A. in Architecture from the University of California at Berkeley. Today he divides his time between Israel and Berkeley. He is world-renowned for his architectural achievements and is also active in photography, writing, lecturing, and illustrating. He has received many awards for his architectural and photographic works, has exhibited and published both in the United States and in Israel. Among his books are: Israeli Synagogues From the Ancient to the Modern, New Israeli Architecture, A Survey of Building Construction in Israel, Greater Jerusalem, and As Time Goes By.

Yosef Shlomo’s son “Shlomo” (Shmuel) was a free spirit and left, what he saw as the constraining Jewish life in Poland, for France. Paris was where he could realize his artistic aspirations. He desired

not only to escape the material narrowness of the ghetto, but also aspired to intellectual liberation… Art had been charged with a new mission, it struggled for expression, for liberation of the soul.

The Jew had his own answer for this. Paris… his soul trembles, it suffers from visionary longing. His emotional world always moves between weeping and laughing… These are the opposite poles around which [Shlomo’s] life revolves. He wants and has to give expression to them so that his soul may be freed of its

505

nightmare. And he finds this expression in art.[43]

Montmarte had long been a haven for Jewish artists. It was there that Camille Pisarro had held sway as “Papa” to the impressionists. Shlomo had heard that perhaps as many as seventy-five percent of the Montmarte artists were of Jewish background and the new crop included the creative genius of Marc Chagall, Amadeo Modigliani, Jules Pascin, Chaim Soutine, Mane Katz, Jacob Epstein, and Jacques Lipschitz. In this atmosphere, Shlomo prospered; not as an artist but as an art and antiques dealer.

If he thought he would escape from Judaeophobia he was quite mistaken. Hatred of Jews was endemic in eastern Europe and Russian sponsored pogroms had made life nearly unbearable. The style in France might have been different from that in Poland but the poison of anti-semitism was still a potent force.

The era which filled liberals with hope for a new world order witnessed the slavery of competitive armaments and the preparation for wars on a terrifyingly large scale. As all Europe breathed a harsher air, a most rabid kind of anti-semitism appeared, taking possession of every country and endangering all that the Jews had laboriously won… Even France, which had been a center for liberalism for several decades, was deeply affected by the new anti-semitism… The culmination of the long period of anti-semitic agitation came in 1894 when a Jewish captain, Alfred Dreyfus, was accused of selling military secrets to the German government. He was court-martialled and summarily condemned to solitary confinement for life on Devil’s Island. His punishment was dramatically advertised when he was publicly degraded in the court of the military school in Paris. Dreyfus protested his innocence to the end.[44]

Dreyfus was later exonerated but the virulence of the anti-semitic explosion was not easily dissipated.

The victory of Dreyfus cleared the good name of the Jews and ruined official anti semitism. Yet the whole affair had disastrous consequences. Years of inflammatory anti-semitic propaganda inevitably increased racial animosities. No progress was possible in a land where one’s very existence was a political question.[45]

It was recognition of this ingrained European trait that empassioned the young

506

journalist Theodore Herzl, who had covered the Dreyfus trial, with Zionist fervor. Others were energized in exactly the opposite direction. They attempted to prove that Jewish background was no hindrance to being true Frenchmen. They adopted French names, emulated French behavior, disassociated themselves from the “anachronistic” Mosaic religion, and completely assimilated into the French nation. The experience of the twentieth century highlights the folly of this path, but in spite of the disillusionment many French Jews continue to proclaim that they are Frenchmen not Jews.

This is the apparent course of Shlomo Charlap’s family. Now called Samuel, he married and had one son. Guy Jose was born in 1921, educated in France, and became a successful international business executive. He married and had five children but Shlomo’s descendants have, to this point, shown little concern for their rich Judaic heritage.

Shmerel, brother of Samuel and the youngest son of Yosef Shlomo, was born in Warsaw on June 1, 1879. His son Teddy lives in Brooklyn {Edward Teddy Charlap, born 1915 has passed away in 2004.}

My father was born in Warsaw and lived there until he was about twelve. At a very early age he left home. His older brother Shlomo was living in Paris and Dad went to live with him. Shlomo was an arty type and was involved in antiques. I believe he was successful but he probably assimilated very rapidly into French life. I know his son Guy considers himself a Frenchman. His Jewish background is unimportant to him. Dad learned the diamond cutting trade and married a woman named Taube Lowenstein, also from Warsaw. Then in 1910 they emigrated to America.[46]

Teddy’s recollections are confirmed by the records. Taube· and Shmerel, then known as Bertha and Sigmund, had left Paris and were temporarily in England, living with Bertha’s brother on Ravensdale Road in London. On September 21, 1910 they boarded the SS Oceanic at its berth in Southampton. Sigmund is listed as a thirty-one year-old jeweler. Bertha was three years his junior. Their destination was a brother-in-law [illegible name] living at 543 Black Avenue, Brooklyn. Sigmund and Bertha landed at Ellis Island on September 28, 1910.[47]

Shortly after they arrived Bertha gave birth to a daughter. Then tragedy struck. Bertha and the baby girl died at about the same time. Dad told me that he was overwhelmed by grief and got on the first boat he could board to get away from New York. He wanted to forget that terrible chapter in his life. He landed in Argentina and worked there for a while as a jeweler. But he was still tormented and couldn’t settle down. He continued traveling around South America and then went back to Europe. He returned to the U.S.A. and married my mother, Grace Osina,

507

who was born in Siedlce. She was ten years younger than Dad. I was born on September 14, 1915. My kid brother Emile came two years later. Dad never lived to see my Bar Mitzvah. He died in January of 1928.

Emile was only ten and I guess he needed a father figure. He was attracted to the Boy Scouts and it was there that he first heard a bugle and fell in love with the sound. He was thrilled with the idea of making music. But we were very poor after Dad died. I was a kid myself and was supporting the family. We had no money to spare for instruments and music lessons. Well, Emile scavenged everywhere and found a beat-up old bugle that was terribly bent out of shape. The kid was determined and with an iron bar carefully straightened it and then polished it. He taught himself how to make notes and then tunes from that relic. Then he found a trumpet in a junk pile and started playing that. We still had no money for lessons but he found another kid who was taking trumpet lessons and bartered for his knowledge of the instrument. Emile would practice seven hours a day blasting out over the rooftops of Brooklyn. The whole neighborhood would complain. By the time he was eighteen he was playing with Bunny Berrigan’s band. Then he played with Xavier Cugat, Benny Goodman, and Ben Bernie. While with the bands he got interested in arranging and landed a job in the new television broadcasting industry. He worked for Sid Caesar on “Your Show of Shows.” From there he worked his way up and became really successful as one of the leading orchestrators in the country. He’s worked with them all – Sinatra, Bob Fosse, Broadway, Hollywood, the Met, the Philharmonic. I’m very proud of him. He never had a music lesson in his life.

I’ve led a more prosaic life. I’m retired as a contract administrator with New York’s Environmental Protection Administration. I was married to Ruby Marcus in 1937 and have two great kids and four grandchildren. My son Robert moved back to a more traditional Judaism and my grandson David is frum. He’s also extremely interested in the family. Both he and his brother Matthew are mathematical and computer geniuses.[48]

Emile Charlap spends his summers on Fire Island, the beautiful beach and barrier island that runs for about fifty miles along the south coast of Long Island. He has instituted a unique cultural tradition, described below, that attracts the elite of New York’s musical world.

The evening was graced with the sublime sounds of a brass orchestra slicing through the sultry air of the selective, sophisticated suburban community of Seaview. A privileged group, crowded onto the deck and lovely landscaped gardens of Emile and Diane Charlap, was privy to an assemblage of the world’s finest musicians as “The Seaview Brass” delivered their seventh annual “Summer

508

Musicale.” How does one entice such a prestigious group away from their lucrative gigs in concert halls and Broadway theatres for an entire weekend at no pay?… “They’re either afraid of me or they love me, I’m not sure which,” said host Maestro Emile, who is one of the biggest music contractors in New York. As such, he hires the musicians, does all the music preparation including orchestrations and manages the music production for practically all the motion pictures produced in New York, plus doing the same for recordings and other musical ventures.[49]

Two years before this Fire Island party, eighty of New York’s most prominent musicians, including members of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, the Metropolitan Opera, the Broadway theatre, and celebrated jazz groups gathered at the fabled Sardis Restaurant to serenade Emile on his seventy-fifth birthday. A press release of the event stated that Emile’s

reputation had resulted in most of the important or big-budget movies of the past fifteen years being recorded here… Charlap began his career as a trumpet player and then became a copyist for numerous Broadway shows including Cy Coleman’s Sweet Charity and the Richard Rodgers-Stephen Sondheim Do I Hear a Waltz. He effected a continuous working relationship with Bob Fosse for both stage productions and movies including Lenny and All That Jazz. Charlap turned to music contracting in the mid 1960s, when the film industry had little presence in New York. Working with what he calls “the world’s greatest, most versatile pool of musicians,” Charlap was responsible for a parade of movies being scored in Manhattan: The Wiz, On Golden Pond, Reds, Ghostbusters, The Cotton Club, Pochahantas. Other of Charlap’s contracting services include hundreds of record albums for artists such as Wynton Marsalis and Carly Simon. [50]

A highlight of the birthday bash was a new arrangement of “Happy Birthday” by eight-time Grammy Award winner, Dave Matthews. Emile was also presented with the Lifetime Achievement Award of the New York Recording Musicians. The ten-year-old boy with the bent and battered bugle had come a long way from his humble beginnings.

Ephraim Zvi Charlap {אפריים צבי חרל”פ}, Sigmund’s older brother, was married three times. His first wife was Esther bat Yaacov Kruschen with whom he had two daughters, Shifra {Shaindel Shifra Shirion, 1881-1911} and Mindel {Mindel Zusman (Charlap) 1883-1966}. Both married but we have little information on Shifra other than she died in Israel. {Shifra children: Esther Keler (Shirion) 1900-1979, Yehezkiel Shirion, Shulamit Frida Gafni (Shirion), Chana Sokolski (Shirion), Sarah Helvitz (Shirion) 1910-1978.} Mindel, born in 1883 was living in Eretz Yisrael in 1908 when she married Menachem Zusman. Shortly thereafter, the young couple emigrated to Australia. They must have taken a boat that traveled east through the Indian Ocean because they settled in Perth. The first of their eight children was born in 1909. Seven Zusman children managed to find Jewish mates in

509

that remote town on the west coast of the sub-continent. There is now a vast family resulting from these marriages which we have barely begun to investigate.

Photo of Efraim Zvi Charlap by Gil Dekel is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Ephraim Zvi’s second wife was Leah Slutsky {לאה חרל”פ לוצקי}, who also provided him with two children, Yisrael {11 Oct 1884 – 30 January 1974} and Tova {Tova Hofshi (Charlap) 1888-1968}. In a collection of documents that Dr. Susan Harlap had provided, I found a letter from Avi Harlap that had been given to Susan’s daughter who was doing genealogical research for a school project. The letter states that “Ephraim made aliyah in 1890 and he was a founder of Rehovoth. I am a member of the Rehovoth Charlaps.”[51] Thirteen years after Avi had written this, I began a correspondence with him which has resulted in a fruitful exchange of information. He pointed out that since his father died over two decades ago, he has been researching the Charlap family. Moreover, he has recorded some of his findings.[52] The following piece is about his grandfather.

Ephraim Zvi Charlap was born on the 15th of Tammuz 1858 in Tiraspole, an area of Moldavia which is in Russia.[53] … His second marriage to Leah Lutsky was arranged by a shadchan. In 1882 he settled in the town of Nezhin in the Chernigov area of the Ukraine. There he became a tobacco merchant. In 1882 he organized a Lovers of Zion chapter in his town and was named Chairman. With the arrival of Hanukah in December of 1889 he made aliyah through Odessa with his wife and children Yisrael and Tova and his daughters from his first wife, Shaindel [Shifra] and Mindel. His wife Leah died in Jaffa soon after they arrived in the Holy Land.

Ephraim moved to Rishon LeZion where he worked in masonry construction together with Aharon Eisenberg. Representatives of Baron Rothschild, patron of Rishon, gave him the right to stay {in the city} but he didn’t approve of the administration and left before long. On the 15th of Av 1890 he moved to newly established Rehovoth and married Yehudit bat Avraham Shpiner, born in 1868 in Kamenetz-Podolsk.

In Rehovoth, Ephraim and Aharon Eisenberg organized the workers and formed Agudat Poalim. Eisenberg had been farming in the Rehovoth vicinity. He worked on the new group’s constitution. Ephraim was the practical organizer who recruited workers, not only from Rehovoth, but also from Nes Ziona, Rishon LeZion, and other settlements in Judea. Among the prominent members were Ephraim Komorov and Menachem Shtemper.

Later, Ephraim Zvi was joined by Aharon Eisenberg, Yitzhak Hayotman, and Noach Shapira in founding Ha’asharot Agudat Achim {אגודת אחים, עשרות}. A secret organization of eighty members, it followed in the spirit of B‘nai Moshe {בני משה} which had been founded

510

by Ahad Ha’am {אחד העם}. Ha’asharot trained members in the use of firearms, followed militaristic discipline and paraded smartly through the city, assisted the sick and injured, and provided defense for the Jewish community.

In 1891, Ephraim Zvi and Aharon Eisenberg formulated a plan for a new type of Jewish settlement with revolutionary rules. The workers of Ha’asharot themselves would own the land. Proceeds from the vineyards would go into a common account. A worker who was too old to work or who was in failing health would be cared for through a lottery. All workers would be represented by a slip inserted in a box. The needy person would select randomly from the box. He would receive the same income as that of the worker on the slip. To realize their ideals, Ephraim and Aharon bought 170 dunams {one dunam is about 1,000 square metres} from Reuven Lehrer at a price of seventy francs per dunam, to be paid out over sixteen years without interest. The land was north of Nes Ziona, called Nahalat Reuven {נחלת ראובן} back then. It was an excellent deal but after the first payment the savings account of Ha’asharot Agudat Achim was empty. They had underestimated the expenses for the training of the workers and the purchase of defensive arms.

Meanwhile Mikhail Halpern, one of the founders of Agudat Hapoalim in 1885, had returned from Russia. He had fell afoul of the Rothschilds and had been banished from Rishon LeZion. Now he returned to Eretz Yisrael with money. Upon hearing of the desperate straits of Ha’asharot, he put up some of his own money and sought contributions from workers and other Lovers of Zion in Jaffa. Sufficient funds were raised to pay off Reuven Lehrer. But the financial crisis had taken its toll. The organization was disintegrating, the moshav was not producing as was planned, and the winery seemed to be on the verge of closing.

Everything came back to life in 1900. Ha’asharot Agudat Achim had set an example of idealistic independence. They encouraged others to follow their lead. The young workers of Rehovoth marched to the Baron Rothschild’s moshav and urged the workers to demand financial independence. The people who lived under the Baron’s dictates must be allowed to forge their own destiny. A little later in that year, workers representing different settlements met in Jaffa and elected a Workers’ Committee. Ephraim Zvi Charlap was the elected representative of Rehovoth. He travelled to Paris to negotiate with the Baron’s court, but his overtures were refused. In February of 1901 the Vaad Hapoel (Committee of Workers) were joined by representatives of the farmers and traveled to Odessa to the headquarters of the Lovers of Zion movement. An agreement was reached on the establishment of Histradut PoalimI {הסתדרות פועלים}, its governing board, and its protocol. In May the committee was received by Baron Rothschild in Paris. Ephraim Zvi Charlap was present at all of these meetings.

Ephraim Zvi built a firing range in Rehovoth and arranged to obtain guns from Ze’ev Tiomkin of the Jaffa Lovers of Zion group. Ephraim also worked with engineer Mordecai Loveman in defining the borders of the moshavot and determining the output expected of them.

In 1903, after a feud between various workers’ groups, an agreement was

511