Gil Dekel, PhD (based on Dr. Goldsmith’s model¹).

Many team-building processes fail because participants are asked to solve other people’s issues instead of solving their own. The following article proposes a process where people take responsibility for solving their own problems, and by that they become more effective and proactive team members.

To build teams (or ‘collegiality’, as Southampton University calls it²) we need to help people self-reflect and choose what change they would like to see in their own performance³. This is known as auto-ethnographic approach⁴.

If staff decide for themselves instead of following a policy that is handed to them, then they take authorship and become more interested in the process success. The focus is on developing relations and inspiring people (not developing policies)⁵.

The process involves choosing a collective behaviour to change, a personal behaviour to change, and peer-feedback.

Step 1 – Check if team-building process is necessary at all.

Ask the team to confidentially circle the scores to two questions:

- “How well are we doing in terms of working together as a team?”

- “How well do we need to be doing in terms of working together as a team?”

Why do this step?

It is important to determine whether the members feel that the process is necessary. In some cases, a few people may report to the same manager, but may have no reason to work together as a team. Other people may agree that team-work is important, yet they may believe that the team is already working well.

– Calculate results.

Have a team member calculate the results. If colleagues believe that there is a need for the process, then proceed to step 2.

Step 2 – Collective behaviour that needs changing.

Ask all members:

“If all members could change two key behaviours collectively as a group in order to improve our teamwork, which two behaviours we should all try to change?”

Write down all behaviours, and have each member choose two.

Ask members to prioritise all chosen behaviours on a chart board (many will be the same).

Using consensus, have members agree on one most important behaviour. This is the collective group behaviour that needs changing by all team members.

Step 3 – Personal behaviour to change.

The members now need to discuss personal behaviours. Have colleagues hold one-to-one dialogues in groups of two. Each member will request from his or her colleague to suggest two personal behavioural to change (other than the collective one agreed already).

Each member should actively ask for this, rather than just sit and wait for the other person to impart the feedback. By actively asking, people take responsibility.

The members can use this question:

“Can you suggest two personal behaviours you think I could change?”

Then, rotate the group. If there are seven members, for example, then each member will participate in six one-to-one dialogues (receiving feedback, and also giving feedback).

These dialogues occur simultaneously and take about five minutes each.

– Decide and announce personal behaviour.

Each member to review their own list of suggested behaviours, and choose for themselves the one that seems most important to them.

Have all members announce their one personal behaviour to change.

You now have one personal behaviour that each member needs to work on individually, as well as the one collective group behaviour for all members to work on.

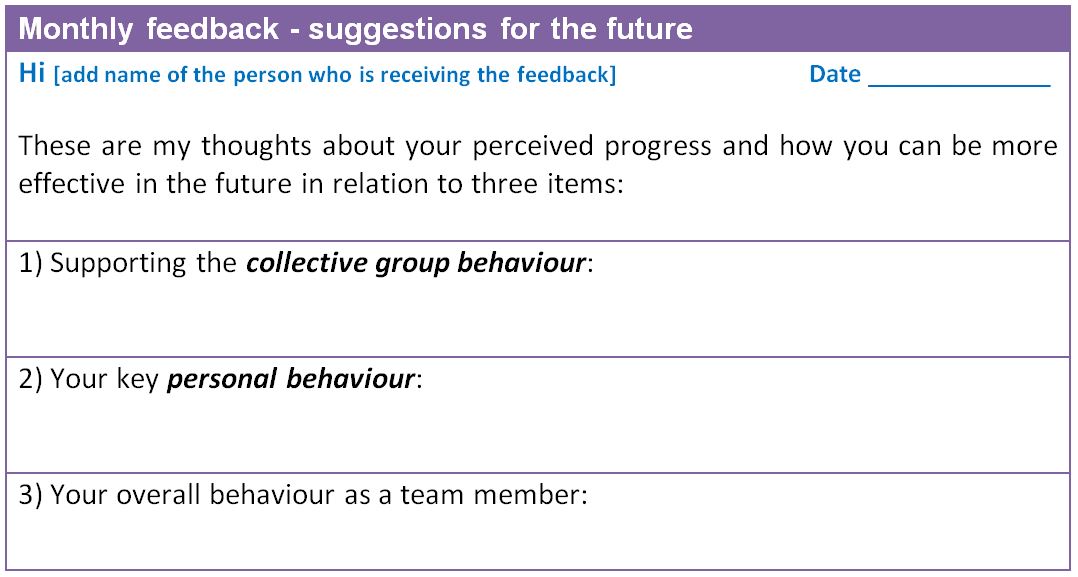

Step 4 – Monthly feedback: suggestions for the future.

Encourage all members to ask for a brief (five-minute), monthly, ‘suggestions for the future’ from all other members. This can be verbally, or you could use the form below.

The monthly feedback ensures that all members are engaging in the process, and receiving comments on their progress.

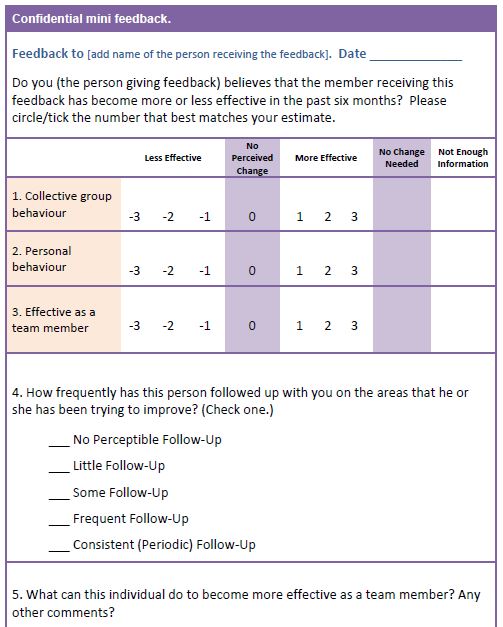

Step 5 – Confidential mini-feedback (6 months).

Follow with a confidential mini-feedback in six months’ time. Each member will give confidential feedback to all other members, relating to five items.

Item number 4 – ‘How frequently has this person followed up’ – helps members see the connection between their amount of follow-up and their increased effectiveness.

– Calculate and disseminate results.

Calculate the average results for each person, for each item 1 to 5.

Also calculate the average result for the whole group on item number 1 – the collective group behaviour.

Each member will receive a confidential summary report. The report will give members a chance to receive positive reinforcement for improvement (and to learn what did not improve) after a reasonably short period of time. It will also help to validate the importance of ‘sticking with it’ and ‘following up’.

Step 6 – Reflective meeting following the mini-feedback.

In a team meeting have each member discuss their mini-feedback results, and have them ask for further suggestions in a brief one-to-one dialogues.

Facilitate a discussion on how the team is doing as a whole.

Provide positive recognition for increased effectiveness, and encourage members to keep demonstrating the behaviours that they are trying to improve.

Step 7 – Confidential mini-feedback (8 months).

Have each member complete another mini-feedback (see step 5) eight months from the beginning of the process.

Follow up with a discussion.

Step 8 – Final confidential mini-feedback (1 year), and reflective meeting.

Have members write a final mini-feedback (see step 5) after one year.

Review the results, and ask the team to rate the team’s effectiveness on where we are versus where we need to be in terms of working together as a team. Compare results with those calculated one year earlier (see step 1).

Give the team positive recognition for improvement, and have each member recognise each of his or her colleagues for improvements, in a brief one-to-one dialogues.

Ask the team members if they believe that further work is needed. If the team say ‘yes’ then continue the process. If the team say ‘no’ then declare victory and work on something else!…

Why This Process Works?

People are far more knowledgeable than they realise⁶. To turn knowledge into practical actions this team-building process facilitates disciplined feedback, peer-review, and encouragements for follow-up.

The process follows what Edward de Bono’s defines as ‘Parallel Thinking’: instead of a judgmental process (yes/no, right/wrong, true/false), this process focuses on design and creation, and on embracing both sides of a situation while seeking to design a way forward⁷.

While self-development is the most effective method in team-building, it does require a high degree of self-critical ability and honesty with yourself.⁸ It is very easy for people to ‘steer away’ from issues, and convince themselves that they are making real progress. For that reason, the process in this article allows for ample feedback from peers, to make sure participants do not delude themselves, rather stay focused on the issue.

Most survey feedback processes ask respondents to complete too many items. In such surveys most of the items do not result in behavioural change and participants feel they are wasting time. On the other hand, participants almost never object to completing a four/five items mini-feedback that is designed to fit each member’s specific needs.

This process provides ongoing feedback and reinforcement, where many other survey processes provide feedback every twelve to twenty-four months. Feedback and reinforcement for new behaviours need to occur much more frequently than yearly or bi-yearly.

The steps in this process do not take too much time and the first mini-feedback will quickly show whether progress is being made or not.

As effective teamworking is becoming more and more important in any workplace, the small amount of time that you invest in this process may produce great return for your team and an even greater return for you organisation.

Footnotes and references:

1. Article’s history:

* This version: adapted and updated by Dr. Gil Dekel, December 2016.

* Previous version: ‘Team Building Without Time Wasting’, January 2012.

* First version: Goldsmith, Marshall., Lyons, Laurence., Freas, Alyssa. (2000). ‘Team Building Without Time Wasting’. In Goldsmith, Marshall., Lyons, Laurence., Freas, Alyssa. (Eds.) Coaching for Leadership: How the World’s Greatest Coaches Help Leaders Learn. San Francisco: Jossey Bass, pp. 103-109.

2. Southampton University. (2016). Southampton University Strategy. Retrieved 10 December 2016, from: http://www.southampton.ac.uk/about/strategy.page

3. Self-made millionaire and financial teacher, Robert Kiyosaki, explains that most people want to change other people but not themselves, yet it is easier to change yourself…

See: Dekel, Gil. (2010.) Key Lessons from Robert Kiyosaki ‘Rich Dad Poor Dad: What the rich teach their kids – that you can learn too’ (review by Gil Dekel, PhD. Part 1 of 4). Section number 40. Accessed 17 December 2016, from: https://www.poeticmind.co.uk/business/key-lessons-robert-kiyosaki-rich-dad-poor-dad-what-the-rich-teach-their-kids-that-you-can-learn-too-review-gil-dekel-phd-part-1-of-4/

4. More on auto-ethnographical methods see: Dekel, Gil. (2012). Inspiration: a functional approach to creative practice. Retrieved 14 Dec 2016, from: http://www.insight.poeticmind.co.uk/5-abstract/

5. Social Entrepreneur, Andrew Mawson, explains that businesses should start with inner dynamics, not with documents or committees. See: Dekel, Gil. (2011). Lessons from ‘The Social Entrepreneur’ book by Andrew Mawson. Sections 4 and 6. Retrieved 17 December 2016, from: https://www.poeticmind.co.uk/business/lessons-the-social-entrepreneur-andrew-mawson-gil-dekel/

6. Dekel, Gil. (2014). Knowing Tools: Knowledge-Extraction Methods. Retrieved 14 Dec 2016, from: https://www.poeticmind.co.uk/research/knowing-tools-knowledge-extraction-methods/

7. See: Dekel, Gil. (2011). Key Lessons from Edward de Bono’s ‘Parallel Thinking: From Socratic to de Bono Thinking’ (a short summary by Gil Dekel, PhD). Retrieved 17 December 2016, from: https://www.poeticmind.co.uk/research/key-lessons-from-edward-de-bono-parallel-thinking-from-socratic-to-de-bono-thinking-short-summary-gil-dekel-phd/

8. Snowden, Christopher. (2016). Email to Gil Dekel. (21 December).

—

This article was written and published with permission of the authors.

Gil Dekel. 18 Dec 2016. Last update 23 Dec 2016.

You can share and adapt this work, as long as you:

– credit the author,

– link back to this page,

– not using for commercial purpose

– share alike

Self-reflective team-building process by Dr. Gil Dekel is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Photo/quote credit: Photo by Gabriel Santiago Unsplash. Quote by Denis-Waitley. Design by Gil Dekel.

- Reading with Natalie, book here...

- Reading with Natalie, book here...