by Gil Dekel, PhD. (About Gil. Contact)

Introduction

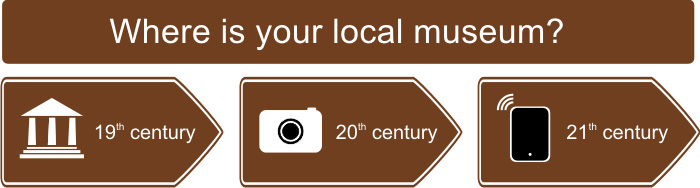

In this paper I will follow the evolution of art museums through the effect of the use of images of artworks. I will argue that the use of images of artworks has contributed to a shift in the role of museums from ‘national treasurers’ institutions that hold artworks, to collaborative ‘international proprietor of knowledge’ that operate as online universal public domain. In this public domain, museums are not managed solely as places to display art, rather as publishers that commission art from artists, and actively engage with online visitors. I will look at the social and historical context in the last 150 years, and will discuss recent developments.

Chapter 1: the modern camera, and the second life of art through images

Until most recently, museums could be said to function as international centres of attraction (Belting, 2007a: 238), drawing visitors from all over the world to their physical premises where artworks were presented. However, the growing numbers of images of artworks online, and with them the growing numbers of e-visitors and e-artists, shift the role of museums today from mainly physical premises of ‘education’ into online ‘collaborators’.

A most recent development that demonstrates this change is Google Art Project, an online tool bringing images from 17 worldwide art galleries, and allowing navigation between collections from the different museums. Some images can be zoomed-in at such level that brush strokes and hairline cracks in the surface can be visible (Kennicott, 2011). This cannot be visible by the naked eye when viewing the real paintings in the museum (Smith, 2011). More so, often large crowds ‘compete’ on viewing a painting in museums, to the extent that the London’s National Gallery is reported “to limit visitor numbers to a major exhibition of Leonardo da Vinci works in an attempt to prevent large crowds detracting from the viewing experience” (BBC, 2011). When viewing artworks from home, online, this problem dispels.

The distribution of artworks’ images is not a new occurrence. Smith (2011) suggests that “most museums have spent at least the last decade — and quite a bit of money — developing Web access to works in their collections”. More so, she (2011) argues that “Google venture is simply the latest phase of simulation that began with the invention of photography…”

Bennett discuses the changes in the role of museums in Britain in the nineteenth century, at the time in which photography was invented. Bennett (1988: 63) explains that museums were transformed from semi-private institutions (visited largely by the ruling and professional classes), into state-controlled institutions (visited by the general public). At the end of the nineteenth century, museums were seen as a major tool by which to ‘educate’ people, turning into what Mclean (1996: 12) calls “temples of self-improvement”.

However, while museums were intended for the people, they were not of the people, in that they did not display works relating to the lives and interests of the working classes in the pre-industrial society. As such, museums tended to promote what Bennett (1988: 64) calls ‘materialisation’ of the power of the ruling classes (see also McTavish, 2008: 228), with collections of imperialists items intending to encourage, according to Ginsburgh & Throsby (2006: 57), an acceptance of the ruling classes.

The promotion of the ruling classes to the working classes visitors, posed a problem in the management of museums and the way they looked to maintain visitors. The ruling classes, and with them high culture, were seen as a pool of specific customers that needed to be retained, but not developed. On the other hand, the working classes, and with them the popular culture, operate on the basis of existing natural market forces (Ginsburgh & Throsby, 2006: 785) – either visitors like the exhibits and come to view it, or they don’t. Exhibits promoting the ruling classes, which did not appeal to the working classes (Ginsburgh & Throsby, 2006: 56), did not conform to the natural market forces of visitors. Museums turned to the camera in an attempt to bridge the gap between the exhibited high culture, and the popular culture, heralding in that way a pop culture, which was later envisioned by the master of photography, Andy Warhol: “In the future everybody will be world-famous for fifteen minutes” (quoted by Brim: 2009, 11).

With the modern camera, photos of artworks were now taken for the purpose of study (Whitehead, 2005: 46), as well as museums’ promotions through the social networking of the time – publications, posters, gallery talks and group discussions showcasing slides of artworks (Smith, 2011). The camera provided a tool that enabled museums a new way of disseminating artworks to the working classes through mass media, in times when “photography was seen as a way of encouraging a more general interest and amateur participation in anthropology and folklore” (Edwards, 2009: 71). As images of artworks made it into the popular media, a link was created between museums’ high culture and mass market culture.

However, the use of the camera to produce images of artworks can be said to work against the natural essence of art itself, with the reproduction of images misrepresenting the art. Walter Benjamin (1983: 21), writing in the 1930s, argues that the authenticity of an artwork cannot be reproduced or recreated. A photo of artwork does not contain the experience of making the artwork, or its ‘presence’, thus it nullifies the historical ‘evidence’ of the work. Benjamin (1983: 22) explains that the image removed the artwork from its historical place and context.

Smith (2011) offers a different view, arguing that images in art books, postcards, posters and slides in art-history lectures “have been providing pleasure for more than a century”, acting as “the next best thing to being there”. If images removed the authentic from artworks, as Benjamin suggests, they may have become an alternative to viewing art itself, as Smith observes. Yet, alternatives to artworks have been produced long before the use of the camera, with art being reproduced throughout history. Students in ancient Greece are said to have reproduce artworks for the purpose of study, and artists reproduced works for commercial purposes (Benjamin, 1983: 18). How different is a camera-reproduction to a man-made reproduction of artwork?

Apparently, unlike the camera, a man-made reproduction still produces an ‘authentic’ artefact, even if new. On the other hand, reproduction of art through creating images with the camera removes the singular and one-time place of the artwork in society. In such way, art is becoming a collective reproduced item that exists in the time when the photo was taken (and not in the time and place when the real artwork was created), and in the realm of the common. The tradition and message of the artwork are destroyed (Benjamin, 1983: 22).

But it seems that this ‘destructive’ act did not lead to annihilation of art, rather to a new form of expression (Savedoff, 2000: 2). Smith (2011) suggests that with the invention of photography, images became individual items that were extending the life of the artwork that they depict; creating “…second lives” for the artworks. It is the first time that art became viral in a way, having an ‘annex’ or extension (the photos of art) that had independent life. Museums begun to incorporate photography as artwork to be exhibited (Whitehead, 2005: 46).

Chapter 2: image-making as art form in itself

As the camera became cheaper, more people could afford to buy one and document their daily lives (Carlisle, 2005: 319). Elite-art was gradually marginalised and photo-making evolved from being an ‘annex’, documenting arts or extending art, into an independent form of art in itself. The work of Félix Nadar (1820-1910) in France is example of the transformation of photography from mere tool of easy documentation (“photography is just a means of printing”, argued Alistair Crawford (quoted by Howard, 1992: 28)) to an art form in itself. Nadar’s photos of famous people, helped transform photography into a popular art, sometimes seen as a “photographic interview” style (Rugg, 1997: 94). Portrait paintings were now competing with portrait photography, on the limited available exhibition spaces in museums. Photography held the aura of art (Van Gelder & Westgeest, 2008: 150) but at a reduced and affordable price.

It should be noted that at the same time (early 20th century) the art world itself moved away from representation of the elite society, to abstract art which favoured artistic expressionism and descriptions of the life of the common people (Harrison & Wood, 2002: 401). If the camera ever competed with art on making art (Kimball, 2002: 145), it has, on the other hand, gone hand in hand with the art world moving into engagement with the day-to-day reality.

As photography became an art form in itself, the gap between the classes was reduced, and more people could now be regarded as ‘acceptable’ artists to showcase their works at exhibitions. Museums became overwhelmed with the amount of applicants (Ginsburgh & Throsby, 2006: 785), winning, in this way, the battle to remain physical institutions that accommodate art. Museums’ role evolved likewise from holder of artworks into commissioners. In the old view, museums were seen as holders of collection of past art, with such regulations as the French law that allowed admission of modern artists to the Louvre only 10 years after their death. This role has changed, and museums turned to act as places of site-specific living-art. Living-art was created for and commissioned by the museums, as Belting (2007b: 34) explains.

The post WWII era could be said to instigate a trend of modern ‘globalisation’. It could be argued that the horrors of WWII may have instilled some common sense and growing consciousness among the world’s nations, relating to the responsibilities that each country holds over the other. While the establishment of the UN after WWII can be seen as mere political tactic, it can also be viewed as a body embodying a global consciousness. In this global consciousness, nations recognise that dire situation in one country can easily evolve into despair that can lead to war (as happened before WWII). Globalisation was further fuelled by the Satellite communication technologies in the 1960s, with the first commercial use in 1969 (Giddens, 1999: 11), allowing for the first time in history an instantaneous communication.

In such a globalised system, the British Museum is reported to envision itself as a ‘museum of the world for the world’ (Belting, 2007b: 33). Of course, one should note that as far as the 19th century, museums all over the world were already founded under British administration (Onians, 2007: 130), yet this seems the result of export of specialism from Britain, and not a globalised co-creation as we can see today.

Globalised co-creation is further exemplified by Guggenheim Museum in NY and the Centre Pompidou Paris, who have established branches in other parts of the world (Belting, 2007b: 33). The Hermitage Amsterdam museum notes in its website (2011) being a dependency of the Hermitage Museum of Saint Petersburg, since its opening in 2009.

The globalised system transformed what Besser (1997) calls “the social and cultural landscape”. Besser argues that culture is now brought into the personal environment where users have more control over how, and how long, they engage with the culture. Until the 1970s, computers were used from particular static physical locations; whereas today development in telecommunications and multi-user systems allows for interactions from different locations, mainly from one’s own home. This benefits museums, as the change from physical to digital media has led to the functional integration of museums with libraries and archives (Marty, 2008: 83), thereby increasing the resources and expertise available to museums.

According to a research commissioned by Arts Council England (2010: 17) over half (53%) of England’s online population have used the internet to engage with arts and culture in the past 12 months prior Nov 2010; and over half of those who are interested in museums were interested in a virtual tour (page 24). The top reason (42%) given for viewing/listening to online recordings of full performances or exhibitions was “because the tickets cost too much” (page 30).

These statistics suggest an alternative, and cheaper, method of engagement with the arts, indicating on an easier route between art-makers and art-consumers. Speer (2011) adds that logistical barriers that prevented artists to connect with buyers, and the difficulty for artists to gain recognition and visibility, have all been removed thanks to the personal computer. More and more artists set up their own websites, showcasing online exhibitions, and setting up online stores to sell their artworks – bypassing, in this way, the physical museums.

More so, the explosion of arts in this online phenomenon seems to develop niches and growing demand for unique arts, with websites offering limited editions of works (Speer, 2011). Museums did not seem to recognise this opportunity, as artists joined together on alternative art platforms – the “multi-vendor websites that supported a large number of artist operated stores” (Speer, 2011).

While museums seem to loose out on many talents who opt for the online route, Travers (2006: 8) suggests that museums still hold authority, acting as centres of scholarship and cultural expertise, and as a source for teaching, mass entertainment and moderation of scientific knowledge (see also Mclean, 1996: 14). Museums seem to harness these qualities, by developing their own websites which reflect that aura of ‘authority’. As file storage capacity constantly increases and storage cost decreases, mass digitization of images becomes a norm, to which museums are adding value online. Museums’ websites provide not just images, information, historical context, and picture libraries of local interests, but also contribute, according to Travers (2006: 8), to scholarly research, mass communication of culture, creativity and ideas. Hence, museums creating a bridge between history, knowledge and the future.

Chapter 3: The shift of museum management in online culture

Weather conditions seem a factor in visitor attendance, with museums seeing an increase in wetter days (British Tourist Authority, 2008: 2). Physical location is likewise crucial for marketing of museums. Prior to the online culture, museums have attempted to overcome venue restrictions through touring exhibitions and turnaround of permanent collections (Mclean, 1996: 130). While we can still see touring exhibitions today, Burton & Scott (2007: 51) argue that there is a “collapse of the physical space in the information-based paradigm”. This collapse can lead the public to see museums not as holder and conservators of artworks, but rather as interpreters of if. Yet, it could be argued that interpretation of artworks is not ‘enough’ engagement with the art.

Viewing a photograph of an artwork online cannot provide the same experience as seeing the work in person. A photograph published on the internet cannot convey the true size of a painting, and a flat two-dimensional photograph of a sculpture may evoke curiosity, but does not allow the viewer to walk around the sculpture and have three dimensional experience to appreciate the work’s power. McTavish (2008: 227) argues that “… the personal experience of art works in real space could not be replicated, no matter how sophisticated imaging devices became”.

More so, with the sharp rise in the value of paintings in the past decade (Feldstein, 2009: 1) online visitors, viewing an image of the works, may not be able to appreciate the gratitude of the artworks, or value their true worth from artistic, cultural or financial perspectives. Museums themselves are often seen as physical places that accommodate the work of the unique talent and visionary artists. In this view, museums are regarded spiritual places where “only those who ‘believe’ come to worship” (Grenfell & Hardy, 2007: 178). This form of ‘faith’ and ‘devotion’ cannot be replicated online, and it seems to be lost in the current e-cultural engagement with the arts.

Instead, museums try to engage with visitors in alternative ways, utilising the new information technologies that offer new ways of bringing information about art collections directly to audiences (Marty, 2008: 84). An example is ‘Connections’, an initiative by Thomas Campbell, director and chief executive of Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY. ‘Connections’ is a simple audio-and-slide-show featured on the museum’s website, bringing the personal inspirations and stories of the curators in relations to artworks. In that way, curators and other staff members are brought “out from behind the curtains…” and connected directly with the online visitors (The New York Times, 2011).

Museums’ managers seem to note that images online can do great deal in enticing visitors. Smith (2011) explains that each museum participating in Google Art Project has chosen one artwork to be photographed at a “super-high mega-pixel resolution” providing extreme zoom. This zoon capacity allows the viewers to “look at Botticelli’s “Birth of Venus” almost inch by inch”. The online viewer gain the benefit of proximity to the artwork, or “…intimacy usually granted only to the artist and his assistants…” (Smith, 2011). Such intimacy is ultimately designed to entice online visitors to visit the museums.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY, found that 40 percent of the people who come to the museum have first visited the website (Kennedy, 2011: 2). The challenge for museums is to maintain e-culture while at the same time turn the curious internet voyeur into a living, breathing visitor that would pay for exhibitions tickets, and purchase at the museums’ shops or cafes. Travers (2006: 17) explains that visiting a museum provides economic benefits beyond the museum itself, with visitor staying at hotels, and buying at local shops and restaurants. In that respect, local governments have interest in promoting museums, and supporting the use of images of artworks online not as an end in itself, but as a starting point to attract visitors to the museums and benefit the whole region.

This raises the question of what artwork may provide the most benefit by being promoted online. There is a distinction between artworks created prior the modern art movements of the early 20th century, and digital works. With exhibits of pre-20th century arts, museums can easily use photographic images as effective marketing tools to entice online visitors to want to see the real artwork. There is no confusion as to what is original and what is a reproduction. But with modern digitally-produced art, that distinction is blurred, as digitally-produced art ‘lives’ online, and not in the physical museums, hence does not seem to encourage viewers to attend the physical museum and help shape regional economy.

It seems that the new e-community provides another challenge for museums, as they may no longer be the main initiator of the engagement with their visitors. Social networking online, such as Facebook, Linkedin and Bebo, allows people to contribute as well as receive information. Individuals can now share content, ideas, interests and recommend on brands. There is no longer a ‘passive consumer’ (Dekel, 2011: 109). Online visitors can “follow their own interests rather than passively submit to institutional authority” (McTavish, 2008: 229), and they develop these relationships mostly on their own initiative, as they decide whether the museum or the museum’s website is important to them or not (Marty, 2008: 95-96). The old paradigm by which art is a human activity sought after by wealthy customers (Ginsburgh & Throsby, 2006: 58) has now gone completely.

Some curators see online social media as the right vehicle to present art altogether, since “…art’s meant to characterize its time and explain what it’s like to be alive now… The art that sums up the present is on the Internet. It’s not in the galleries; it’s not in the museums” (Cain Miller, 2011). Tate Museum director, Nicholas Serota, explains that “The challenge is, to what extent do we remain authors, and in what sense do we become publishers providing a platform for international conversations?” He adds that “…in the next 10 to 15 years, there will be a limited number of people working in galleries, and more effectively working as commissioning editors working on material online” (Higgins, 2009).

This trend has already gained momentum, with such as the Museum of Migration inviting the public to upload photographs to be used by the museum (Manzoor, 2011). Another example is the British Museum 2010 joint venture with the BBC on the project ‘A History of the World in 100 objects’. This project invited audiences to participate actively by adding their own stories and images to the web exhibition (see: http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/about).

But it seems that the commercial market is one step ahead of the museums’ initiative to commission works from the public. Dekel (2011: 116) describes Reeves & Knell’s Co-creation marketing model, which seeks to transform consumers into co-creators of products:

“In enhanced word-of-mouth marketing, consumers who favour a product would blog, review, and support the product. Companies seek more than just supportive consumers. They seek to engage in conversations so to transform the consumers to co-creator, in a way that consumers will help suggest ideas and create the next products that they themselves want to see and buy. Consumers as producers or co-creators” (Dekel, 2011: 116).

If museums can follow this commercial trend in the market, then indeed “The future has to be, without question”, as the director of the British Museum announced “the museum as a publisher and broadcaster” (Higgins, 2009).

Conclusion

Reproductions of artworks through use of the modern camera in the 19th century have provided a new way for museums to connect with their audiences. Museums incorporated photos of artworks in the media, posters, postcards and educational activities such as lectures, slide shows and gatherings. Gradually photography moved from being an ‘accessory’ that promotes arts, into an art form in itself, which was then exhibited in museums.

The mass reproductions of images of artworks online created a dual way of communication, where online visitors have more say and influence over the way they engage with museums. Online visitors are taking the lead in deciding how much and how long they spend time and money with the arts. Museums responded by developing their own websites, aiming to entice online visitors to visit the physical museums, through interactive use of images of artworks online, as well as sharing ‘behind the scenes’ stories about the museums staff and management. Museums also retained the aura of the authority and scholarly centres in relation to art study, and developed online initiatives and collaborations with universities.

Observation and suggestion for the future

Online technologies has not just shifted the way we engage with arts (images, films and interactions using mobile devices), but also changed the boundaries of museums from physical ‘solid’ places into virtual and wireless ‘conceptual institutions’ that must emphasise communications more than instructiveness.

It seems that in relation to grasping the opportunities of online technologies, museums tend to re-act rather than lead. Museums’ professional seem to associate change “… with anxiety and risk rather than with creativity and renewal” (Peacock, 2008: 341), and Information Technology is “… understood as a force from the external environment that has ‘impacts’ upon organisations” (page 343). Since museums are competing for people’s time, a “…wait-and-see attitude from many institutions” (Smith 2011) will not inspire visitors in today’s culture where “It’s either a visit to a museum, or watching television, or a drink with friends. Museum is not something extra; it is something else” (MacLeod, 2011: 15).

If museums can see themselves as integral part of the natural evolution in society, then they will shift from mere places that preserve cultures, into places that collaborate with their visitors. This will be in line with today’s tendency where online technology shifts individual consumers from ‘passive’ to ‘active’.

Bibliography

Arts Council England. (November 2010). Digital audiences: Engagement with arts and culture online.

BBC. (9 May 2011). Leonardo da Vinci show visitor numbers to be capped. BBC News Entertainment and Arts. Retrieved 9 May 2011, from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-13332339

Belting, Hans. (2007a). ‘The Global Future of Local Art Museums: The Cultural Practice of Local Memory and the Rise of Global Art.’ In Weibel, Peter & Buddensie, Andrea. (Eds.) Contemporary Art and the Museum: A Global Perspective. Hatje Cantz: Germany.

Belting, Hans. (2007b). ‘Contemporary Art and the Museum in the Global Age.’ In Weibel, Peter & Buddensie, Andrea. (Eds.) Contemporary Art and the Museum: A Global Perspective. Hatje Cantz: Germany.

Benjamin, Walter. ([1936] 1983). The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Poalim: Kibutz Meuhad, Israel [published in Hebrew].

Bennett, Tony. (1988). ‘Museums and ‘the people’’. In Lumley, Robrts. (Ed.) The Museum Time Machine. Routledge: NY, USA.

Besser, Howard. (1997). The transformation of the Museum and the way it’s perceived. Retrieved 4 May 2011, from: http://besser.tsoa.nyu.edu/howard/Papers/garmil-transform.html

Brim, Orville G. (2009). Look at Me!: The Fame Motive from Childhood to Death. University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, USA.

British Tourist Authority. (2008). Visitor Attractions Trends in England – 2007, Annual Report. VisitBritain/British Tourist Authority: UK.

Burton, Christine & Scott, Carol. (2007). ‘Museums: Challenges for the 21st century’. In Sandell, Richard. & Janes. Robert R. (Eds.) Museums Management and Marketing. Routledge: Oxon, UK.

Cain Miller, Claire. (2011). Social Media as Inspiration and Canvas. The New York Times. Retrieved 6 May 2011, from: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/17/arts/design/flickr-photos-and-vimeo-videos-as-artwork.html

Carlisle, Rodney. (2005). Scientific American Inventions and Discoveries: All the Milestones in Ingenuity From the Discovery of Fire to the Invention of the Microwave Oven. Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA.

Dekel, Gil. (2011). Key Lessons and Concepts from ‘The 80 Minute MBA’ Book by Richard Reeves and John Knell (summary by Gil Dekel, PhD.) Retrieved 6 May 2011, from: https://www.poeticmind.co.uk/business/key-lessons-concepts-the-80-minute-mba-book-richard-reeves-john-knell-summary-by-gil-dekel-phd/

Edwards, Elizabeth. (2009). ‘Salvaging our Past: Photography and survival’. In Morton, Christopher & Edwards, Elizabeth. (Eds.) Photography, Anthropology and History. Ashgate Publishing Group: Farnham, UK.

Feldstein, Martin (Ed.) (2009). Economics of Art Museums. University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA.

Giddens, Anthony. (1999). Runaway World. Profile Books: London, UK.

Ginsburgh, Victor A. & Throsby, David. (2006). Handbook of economics of art and culture. Vol 1. Elsevier: Oxford, UK.

Grenfell, Michael & Hardy, Cheryl. (2007). Art Rules: Pierre Bourdieu and the Visual Arts. Berg Publishers: Oxford, UK.

Harrison, Charles & Wood, Paul J. (Eds.) (2002). Art in theory, 1900 – 2000: an anthology of changing ideas. Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK.

Hermitage Amsterdam Website. Retrieved 13 April 2011, from: http://www.hermitage.nl/en/hermitage_amsterdam/van_amstelhof_naar_hermitage_amsterdam.htm

Higgins, Charlotte. (2009). Museums’ future lies on the internet, say Serota and MacGregor. Guardian. Retrieved 6 May 2011, from: http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2009/jul/08/museums-future-lies-online

Howard, Peter. (1992) ‘Landscape and the art referent system’, Landscape Research, 17: 1, 28 – 33.

Kennedy, Randy. (2011). The Met’s Plans for Virtual Expansion. The New York Times Company. Retrieved, 6 May 2011, from: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/12/arts/design/12campbell.html?pagewanted=2&_r=1&ref=metropolitanmuseumofart#

Kennicott, Philip. (2011) Google Art Project: ‘Street view’ technology added to museums. The Washington Post Online / Arts and Living. Retrieved 7 April 2011, from: http://voices.washingtonpost.com/arts-post/2011/02/google_launches_the_google_art.html?hpid=moreheadlines

Kimball, Roger. (2002). Art’s Prospect: The Challenge of Tradition in an Age of Celebrity. Cybereditions Corporation: Christchurch, New Zealand.

MacLeod, Hugh. (2011). Evil Plans: Having Fun on the Road to World Domination. Portfolio/Penguin: USA.

Manzoor, Sarfraz. (2011). Call for snapshots of migration. Guardian online. Retrieved 6 May 2011, from: http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2011/may/04/migration-museum-photography-competition

Marty, Paul F. (2008). ‘Museum websites and museum visitors: digital museum resources and their use’, Museum Management and Curatorship, 23: 1, 81 – 99.

Mclean, Fiona. (1996). Marketing the Museum. Routledge: London, UK.

McTavish, Lianne. (2008). ‘Visiting the virtual museum: art and experience online’. In Marstine, Janet (Ed.) New Museum Theory and Practice: An Introduction. Wiley: Chichester, UK.

Onians, John. (2007). ‘A New Geography of Art Institutions’. In Weibel, Peter & Buddensie, Andrea. (Eds.) Contemporary Art and the Museum: A Global Perspective. Hatje Cantz: Germany.

Peacock, Darren. (2008). ‘Making Ways for Change: Museums, Disruptive Technologies and Organisational Change’, Museum Management and Curatorship, 23: 4, 333 – 351.

Rugg, Linda Haverty. (1997). Picturing Ourselves: Photography and Autobiography. University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA.

Savedoff, Barbara E. (2000). Transforming images: how photography complicates the picture. Cornell University Press: NY, USA.

Smith, Roberta. (2011). The Work of Art in the Age of Google. The New York Times Online / Art & Design. Retrieved 7 April 2011, from: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/07/arts/design/07google.html?pagewanted=2&_r=1

Speer, Dennis. (19 April 2011). Evolution Of The Online Handmade Industry. Ezine Articles. Retrieved 6 May 2011, from: http://EzineArticles.com/6194387

The New York Times. (11 February 2011). Thomas P. Campbell. Times Topics. Retrieved 8 May 2011, from: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/12/arts/design/12campbell.html?ref=metropolitanmuseumofart

Travers, Tony. (2006). Museums and Galleries in Britain: Economic, social and creative impacts. The London School of Economics and Political Sciences (LSE): London, UK.

Van Gelder, Hilde & Westgeest, Helen. (2008). Photography between poetry and politics: the critical position of the photographic medium in contemporary art. Leuven University Press: Leuven, Belgium.

Whitehead, Christophe. (2005). The public art museum in nineteenth century Britain: the development of the National Gallery. Ashgate Publishing Company: Aldershot, UK.

11 July 2011.

© Gil Dekel.

- Reading with Natalie, book here...

- Reading with Natalie, book here...