Dr. Iain Biggs interviewed by Gil Dekel.

Gil Dekel: I get the feeling that your paintings suggest a sense of environment, a sense of “earthiness”… Is this correct? [1]

Iain Biggs: “Earthiness” means such different things to different people… but I can say that I am concerned with making images that in part – and only in part – grow out of my response to particular places, for example, the small parish of Southdean on the English/Scottish border. I am also concerned with the interweaving of the physical practices and matters of painting and similar craft activities used in image making – in paintings, enamel pieces and, more recently, drawings into old roof slates – with the mysterious business of image as somehow an evocation, an almost-sign. [2]

Are you using your body to empower the messages in your works? [4]

The kind of work I make is very much the result of a physical process and, inevitably, that’s a bodily activity through which the piece is “performed” into being. So I guess the short answer is “yes”. At a less literal level, much of the research and just plain wandering about that informs the work comes from walking in the physical landscape, smelling it, getting cold or hot or wet in it; paying attention to sound and wind direction and light is also important to my sense of wellbeing. To some extent this probably informs the way I approach the work. But there’s also more cerebral stuff cutting across this – stuff to do with mapping, for example – and then there’s also the whole business of practice as a conversation with what other people who make material images have come up with, a conversation carried out through the body pushing stuff around. [5]

How do your paintings change in relation to changes in your life? [6]

My work has changed fundamentally as a result of my daughter becoming increasingly seriously ill. Some of this had to do with what I realised – in retrospect – was a preoccupation with kinds of images that allowed me to mourn my daughter’s loss of an active life. Much of it has to do with the logistics of balancing different responsibilities – as a parent, a partner, a full-time academic, a back-up carer, somebody who needs to make images, who likes to work collaboratively, who needs to write, etc. And then there’s part of it that has to do with getting older – I’m now two years off sixty… and the quite proper shift in one’s priorities and understanding that follows from that. [7]

Can art practice be said to have a therapeutic effect? Can it help release emotional burdens? [8]

Although I have worked closely with art therapists in an educational and training context, have read post-Jungian psychology most of my adult life, and spent a long time in counselling, I’m still very uncomfortable with seeing art practices as strictly therapeutic in any privileged way. Is making a painting more therapeutic than building a dry stone wall? It surely depends far more on who you talk to while you’re going about it? [9]

I need to add that my reluctance to see art practices as privileged therapeutically has nothing to do with the common art world snobbery about the status of “therapeutic art”, but rather with the way many people understand therapy as being about “cure” rather than an exercise in attention – about exchange in its broadest sense as paying attention to, caring for, the other. I learned from James Hillman to understand the term “psycho-therapy” in something like its original Greek sense – as “care of/for the soul”. [10]

Do you think we could talk about the role of art in society and how can art benefit people? [12]

“Art” and “Society” (capital “A”, capital “S”) are all too often cultural “Power Words” that people use like big sticks to fight battles with; battles that are very often far more about their own personal power and prestige than the complex realities that make up our complicated and contradictory experience of the arts and of societies. I’m what might be called a “secular polytheist” (that is, a polytheist in a psychological, rather than theological, sense). So I prefer to think in terms of the different roles of the various very different arts and of the many different roles and approaches adopted within the same art, and about how all these differences (and the commonalities too) inform and function within different societies and sections of societies. [13]

It seems as if you have a kind of a vision of ‘uniting all artists’. Is this correct? [14]

No. I try to avoid having those kinds of visions, particularly if they involve artists, since, psychologically speaking, it’s all too often the case that the visions of unity end up “having us” in fairly horrendous ways. My mantra – if I were to have such a thing – would almost certainly be Geraldine Finn’s statement that, “we are always both more and less than the categories that name and divide us”. I always feel the ethical and social force of this observation particularly strongly whenever I hear somebody say, loudly and in a public place: “I’m an artist”. [15]

You have suggested that doctoral studies in the arts be seen as a means for empowering students to deepen their practice, and thus create new knowledge. How can art practice inform theory, and how can it act as a method, resulting in a PhD thesis? [16]

I don’t think we “do” doctoral studies in the arts so much as with and through an arts practice and our reflecting on that practice. [17]

There are at least four closely interwoven but ultimately distinct aspects to doctoral work that involves art practice as an active research element. I’ll try and say something general about these but, obviously, they each take on a very different status and importance depending on what each different student wants from her or his studies. [18]

One pair of strands is institutionally located in a formal sense within the university, but inevitably involves us always looking over our shoulders at the institutions of the art world and at the specifics of our own particular creative practices. Of these two strands, one involves us in learning to negotiate the PhD as an institutional “gate-keeping” exercise. After all, traditionally a PhD bestows the academic authority that then licences the successful candidate to teach in a university. The second strand here is educational in what I would call the “proper” sense. It’s the process by which we assist in our own transformation through engaging in the experimental processes of genuine learning. This institutional/educational pairing is more or less exactly mirrored by the two other strands. These have to do with navigating the tension between two understandings of art. On the one hand “art as research” as understood by those of us who work full-time in universities while retaining some toehold in the “art world”. That is art as a prospective and thoughtful psycho-physical activity for exploring (researching) our experience of the world. On the other hand art as understood as a commodity in the free-for-all of the art world as a marketplace and all that goes with that. [19]

All this can be seen as a (very real and serious) four handed game played out in the “debatable land” between the official networks, values and institutional politics of the university. Of course we’ve got to remember that the university is both the site of the production and authorization of “official” knowledge and, at one and the same time, also the site of educational possibility. In the same way, of course, the apparently anarchic (sometimes knowingly nihilistic) world of the art market – an even more highly institutionalized site than the university – is, again at one and the same time, also the site of imaginative work as the medium of an educational possibility. I think this is why Joseph Beuys told me long ago to always remember that education is more important than art – something it took me a good while to understand and even longer to accept. [20]

To navigate all this the student has to learn to “dance the dance” without forgetting that it’s just that, a formal dance for which it is necessary to learn the steps but within which variation and innovation are possible – albeit of course a dance in which one can win prizes or, alternatively, fall down and hurt oneself. [22]

Secondly, yes, there’s the business of new knowledge – perhaps better seen as new understanding. Maybe this is sometimes achieved by showing theory the wonder(ing) of the particular, even of the unique. That’s important because Theory (in its “pure”, “militant” or “fundamentalist” incarnation) needs to be constantly reminded of what it too often forgets. A “forgetting” that often leads to marginalization and bullying of people whose lived experience does not “live up to” theoretical expectations or demands. This takes us back to Geraldine Finn. But of course it’s also important to say that we need theory, it’s rigor and overview… [23]

Interwoven into all this there’s also the all-important business of how, at the end of the day, this process helps the doctoral student pay her or his rent! [24]

It sounds as if you talk about the notion of changing the role of art from passive to active? [25]

Possibly, but I’m less interested in attempts to “change the role of art from passive to active” than to try and see my way around our obsession with preserving some predetermined notion of “the role of art”. In my view, what’s most interesting about what we call the arts is that they provide a body of unstable but longstanding practices that, like old folksongs and the best children’s games, constantly mutate into something almost new without ever quite letting go a certain something that we find both obscurely useful and deeply satisfying. [26]

The “role” of art – if we can say that – is, at least in my view, closer to certain understandings of play as a mediation between the known and the not known than of change/therapy in its instrumental form. [27]

All human activity that involves the exercise of some degree of care, skill and attention in its execution has some aesthetic dimension. A large part of “our” problem with regard to the arts is that we still believe that “aesthetics” is something invented in Western Europe by modern philosophers. I was fortunate enough to be taught at the Royal College of Art by the late Philip Rawson. He introduced me to Indian aesthetics and specifically to the Tantric aesthetics based on rasa that was set out by Abhinavagupta (who lived from approx 950 to 1020 AD). As a result, and in line with the thinking of James Hillman, I’ve come to think we need to pay far more attention to the enactment or performance of the aesthetic in human experience, not less. We need to do so precisely because it engages us environmentally with sensate “messages and wisdom” in their felt immediacy. [28]

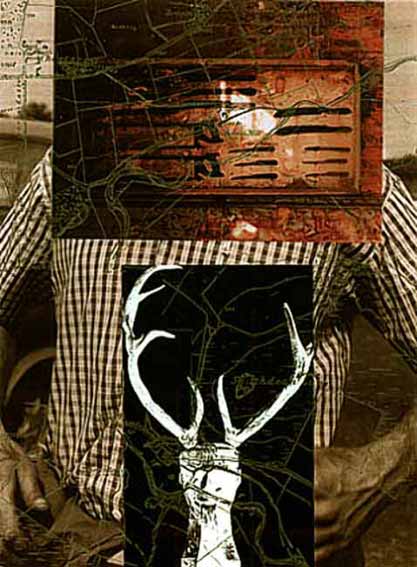

Figure 4: Image from ‘Between Carterhaugh and Tamshiel Rig: A Borderline Episode’ (Bristol, Wild Conversations Press, 2004).

Some artists argue that practice, such as painting, is an act that goes with ‘no thinking’, or that it is ‘to think visually’. In a way, paintings can be seen as patterns of thoughts. Would you agree? [30]

In practice (!) of course there is no such thing as Practice – only various practices and the historical traditions that inform them (painting among them). Currently the conscious mind is seen as analogous to a tiny island floating in a vast sea of so-called “unconsciousness”, which links to the whole issue of tacit knowledge. Yes, paintings, but also of course wallpaper, can be seen as “patterns of thought” but what matters is less whether we “think visually” but whether we work with images (in the fullest sense). Do we let them work on us in ways that are imaginatively transformative of our habitual life and understanding, or that are “enchanting” in an ethically restorative sense? [31]

I don’t mean to sound impatient with the question, but so much of what artists argue about seems far more concerned with allowing them to see themselves and their practices as “special” and/or “exclusive” when what is important is common to all sorts of imaginative practices at large. [32]

How do you see the author of art then? As a mediator between an artistic source and the viewer, or as the source itself perhaps? [33]

One way to answer this question would be to regularly remind ourselves that Roland Barthes was quite happy to receive his royalties as a named author until the day he was killed by an ambulance! [34]

Seriously, we’re all thrown into the world as plural beings in which an almost infinite number of prior beings have some kind of an afterlife, whether through genetic or cultural influence. So “who” exactly would we name as writing the book, painting the image, etc. as “the author”?… [35]

» Academic research methods: ‘Listening to Yourself’…

20 November 2008.

Images © Iain Biggs. Text © Iain Biggs and Gil Dekel.

Interview conducted via email correspondence Oct/Nov 2008.

Iain Biggs is based in Bristol, UK. Gil Dekel is based in Southampton, UK.

- Reading with Natalie, book here...

- Reading with Natalie, book here...