The art of hand papermaking: creating from and against nature

14 February 2024 – Vol 2, Issue 2.

The art of creating paper by hand is known as hand papermaking, an art form with a long tradition and history. When creating paper, you can feel that tradition from the moment you submerge your hands in the moist pulp. In this article, I will share the inspiration and process behind making paper.

Hand papermaking originated in ancient China (2nd century AD), but only entered the Western world in the Early Modern period (15th – 18th centuries), except for countries under Islamic rule in which papermaking was adopted earlier. Many artistic practices are older than papermaking, yet the process of hand papermaking, characterized by motion and repetition, provides a sense of ritualistic practice reminiscent of ancient wisdom. This is not intellectual wisdom; rather, it is wisdom that resides in your hands, in the practice and the intuition that leads you. You intuitively know when your paper is good and ready. You may not know its final appearance, but, similar to breadmaking, the process of waiting and doing provides pure satisfaction that only manual work can offer. Of course, the ultimate outcome is anxiously anticipated, but you learn to appreciate the small steps on the way, as they constitute the essence of your effort.

Handmade paper. Photo by Women’s Studio Workshop, Flickr. Photo licensed under Creative Commons BY 2.0 Deed.

The process of making paper begins with pulp. In earlier days, pulp was made from trees and their fibres, usually from the mulberry tree. However, becoming more aware of the environment and realising how much wood was required for the process, people began using other materials for papermaking that cause less harm, and that are easier to acquire and use in homes or small offices. With this, a new era emerged in which the artistic aspects of papermaking flourished, as new materials and processes allowed for new thinking. Similar to many art practices, the process began as a solution to a problem, later evolving into a mode of expression, an art form in itself.

Many artists began to see a potential for experimentation that lie in the complexity and challenges presented in the process – the intricate steps of fibre preparation, sheet formation, pressing, and drying. These processes require a certain level of skill, precision, and understanding of the materials. The challenges of achieving the desired texture, thickness, and appearance of the paper, provide a fertile ground for artistic exploration.

I found myself on that path when I discovered that I could make recycled paper on my own. I started to make tools for papermaking – wooden meshes attached to frames that could hold pulp when submerged in water. Making pulp was an easy task: tearing old papers, notebooks, cardboard packaging, and soaking them in water until their structure weakened. Somehow this gives you a feeling of creation, of starting anew. The next step is to blend the materials into a fine pulp. The colour of the pulp is determined by the materials, and it will determine the resulting paper. As I experimented, I also started to explore natural dyes.

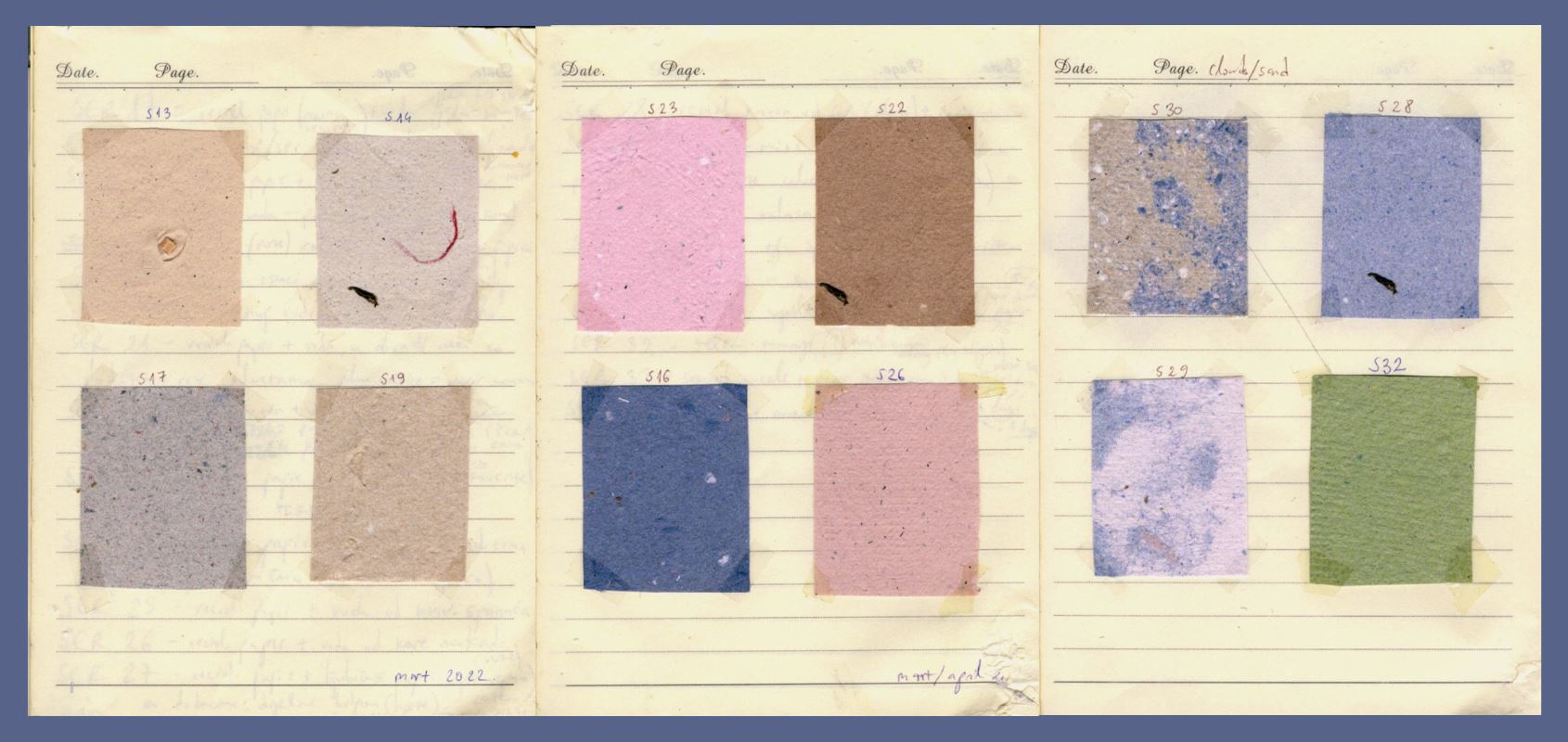

Notebook with paper samples, handmade paper by Katarina Djosan. Photo: © Katarina Djosan.

Making pulp for handmade recycled paper is a simple task, but it does take time… Once you immerse the pulp in water, something strange occurs – you enter an unknown territory, dealing with materials that are neither old nor new. This transition is followed by the sound of water as your hands dip into a bowl filled with floating pulp, creating waves while you firmly hold the framed mesh, waiting for the right moment to capture the pulp. Catching the pulp (similar to catching a fish) is a task that needs to be repeated, especially if you are a beginner. It was one of the most precious moments of creation I’ve experienced. In that exact moment, you feel not only inspired but also connected to people and places before you, to a time past but enduring. On a conscious level, you recognize that you are following the path of an old practice, an ancient craft, using your own hands as people did a long time ago. On an unconscious level, you sense that something more than a practice is unfolding. You make waves and catch, you produce something for the love of the feeling, but also something useful (at least it can be). You feel that the craft is alive, and that you are connected to the cycles and rhythm of life itself – giving and taking, repeating, making mistakes, trying again, all while the water caresses you.

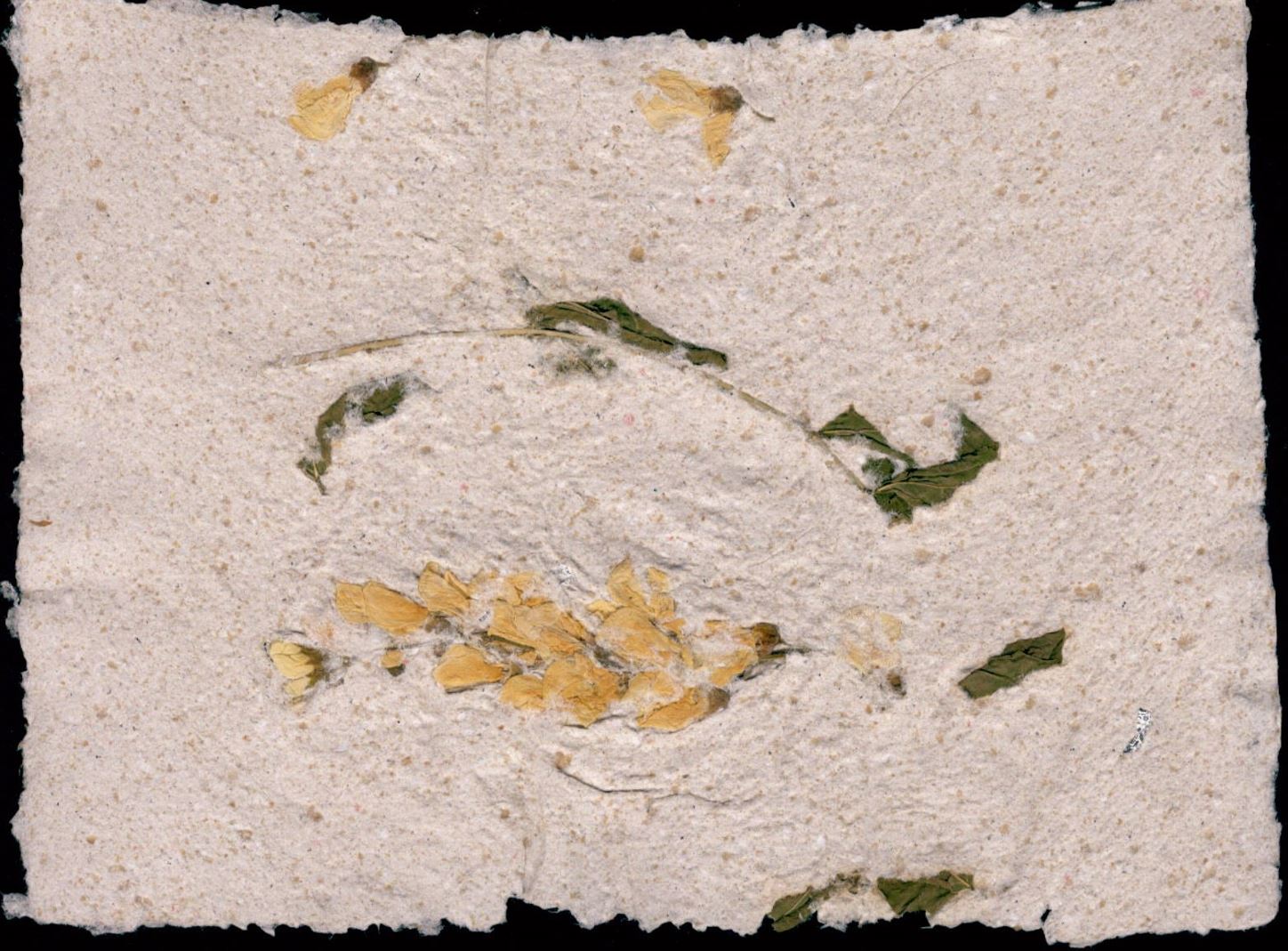

Handmade paper with wax and acacia, by Katarina Djosan. Photo: © Katarina Djosan.

Here, the act of creation is similar to a battle and a collaboration. It feels like a battle as you conquer the strong will of water, which tries to mess with your intentions and prove you wrong – ‘this paper is not going to be perfect’, you know it… But sometimes, you catch the rhythm, and your hands holding a meshed frame not only follow the water flow but make it work to your advantage – you see that the pulp takes the perfect shape, perfect borders, and beautiful colour. You know that you did a great job. From the pulp you made, not two papers are the same. You only need to be inspired by that motion and conquer the water flow or follow it, to make each paper look beautiful and exciting. When working with nature, the same processes produce different results. You get captivated by it – some predictability, some surprises; and you start to act upon it all.

The production of hand-made paper. Photo by Gryffindor, 2008. Image licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

I sometimes think ‘here is the rough edge of paper I don’t like’, but with some tender flowers added to the pulp prepared to be pressed, it would give me that feeling I want. It provides the contrast I was looking for, delivered in a way I believe holds something important, some valuable information or feeling, something livable.

Handmade paper with Robinia pseudoacacia (false acacia), by Katarina Djosan. Photo: © Katarina Djosan.

On other times, I add fine little stones or pieces of wood, or wood dust into the pulp ready to be pressed and dried – just because the paper looks too perfect and does not show the process it went through… In this way, the making of handmade paper can inspire and allow you to reveal the ‘real’ side of the material, even if the ‘real’ was artificially added to enhance your idea.

Handmade paper with stones, by Katarina Djosan. Photo: © Katarina Djosan.

I believe that every artist concludes that sometimes adding (or taking away) can make a big difference to the final result. Making the paper perfect, neat, and tight is beautiful, but as I want to emphasize something by it, to showcase the process, the emotion, or the idea, I intentionally add something to create contrasts or holes that make you ask questions or feel something.

Nicolaus Pevsner stated in the introduction of his famous book on architecture (Pevsner, 1942) that a bicycle shed is an object, not architecture. He believed that architecture is something more complex, an art form that is never just functional. Many years later, the postmodern architect Peter Eisenman claimed something similar. He argued (Eisenman, 2006) that art, including architecture, transcends mere order and perfection, suggesting that the essence lies in the excessive elements intentionally or unintentionally incorporated. Complexity over strict functionality. In this view, art becomes a reflection of diversity and individuality, as the eclectic and subjective meet. The idea is not to just add something for mere adding (although I believe Eisenman would like that), but to add something that in the end transforms a craft product into an art product.

In the process of learning hand papermaking techniques, I realized that every material used gives a very different result and inspires in different ways. For example, making paper from plants is very different from making recycled paper. When I first started making paper from small plants (leftover spinach stems), this required cooking and altering the structure of the plant to create something different. This was an experience of alchemy. I was using something that would typically be thrown away, yet it was still alive, unlike recycled papermaking. The core process is the same – blending, making pulp, transferring it to water, using mesh frames, and pressing and drying paper at the end – but the material was alive and had a structure that wasn’t so easy to dissolve. The long process gave me insight into the resilience of nature, which appeared to me almost indestructible.

While working on plant-based paper, I realized that even if something or someone dies, everything around it still reflects it. Paper made from spinach stems and leaves remains green after hours of cooking; it is still prone to moulding after hours of drying; and it is ‘alive’ to the touch, regardless of my desire for it to feel like a regular piece of paper. Moreover, a whole bunch of spinach stems gave me just one sheet of paper. I was struck by the fact that nature is so stingy yet so resilient. All the papers I made from plants required special treatment, and have always produced different results. I saved them as if they were of greater importance. I realized how much we actually waste nature around us while at the same time realizing how nature resists our efforts to manipulate it.

Handmade notebook. Photo by Meelika Marzzarella. Photo in public domain.

Alois Riegl, one of the greatest art historians of all time, argued that the material from which we make our art is stubborn, as if protesting our efforts to remake it. Contrary to what many art historians argued, he stated that the material does not help artists express themselves but rather acts as a burden to our creativity, and that art making is actually a “continuous struggle with material” (Riegl, 1893: 33), giving us a hard time trying to conquer and translate materials into our language. His theory proved true through the process of papermaking, at least for me. The pleasurable process of papermaking, which I enjoyed so much, offered satisfaction because I had to find a way to obey the material and express myself at the same time, which was never easy. As with the waving water and the resilient natural materials, the same thing happened at the end of the process – I counted on wind and air to yield the desired result.

Hand papermaking is an intriguing ‘call’. Its complex nature becomes apparent only when you attempt to turn it into art – adding, conquering, taming, or embracing the fluid and unpredictable aspects of the work; and the resulting outcome, which never relies just on you, is showing up in front of you. The process teaches you to abandon strict rules and to adapt to changes. At the same time, it encourages you to revisit the same process many times to perfect it and make it your own. It teaches you patience when you just strive for expression. It is a relationship in which nature both gives something to you and expects something from you in return. You need to feel it and break away from it. This is never easy, but in a way, it is always satisfying.

© Journal of Creativity and Inspiration.

Images copyright as specified.

Katarina Đošan received her Master’s degree from the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Belgrade, Serbia. Her thesis concerned the question of the history and methodology of art history, as she was intrigued by different approaches but similar forms of art historian writings. She works at the National Museum of Serbia as an archivist and a curator, handling and researching archival documents, artists’ legacies, sketchbooks, and photo documentation. She also writes for the online magazine PLEZIR, based in Serbia, on art, sustainability, and culture.

References

Eisenman, P. (2006) The formal Basis of Modern Architecture. Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers.

Pevsner, N. (1942) An outline of European Architecture. London: Penguin books.

Riegl, A. (1893) Problems of Style. Foundations for a History of Ornament. Reprint, Princeton: Princeton Legacy Library, 1993.