How inspiration unfolds when writing about artworks

14 February 2024 – Vol 2, Issue 2.

The process of writing about art (for journals or magazines) is usually seen as a process of deciphering the artworks and chopping them into nice pieces of information. The pieces are designed to inform other people on how they should see artworks, art periods, movements, or ideas. That process usually starts with choosing an art form as a focus. Art historians or critics tend to say something about the visual aspects of an artwork as a general introduction, to help make artworks understandable to people outside of the art profession. “In every group of travellers”, argues Baxandall (1979, p. 454), “every bunch of tourists in a bus, there is at least one man who insists on pointing out to the others the beauty or interest of the things they encounter, even though the others can see the things, too: we are that man, I am afraid, au fond”.

‘Writing Art’ by Gil Dekel and image-generating AI, 2024. © Gil Dekel.

This process, which is part of the profession of art historians, is followed by graphics and detailed information about the form, and is then followed by assigning meanings to different sections of the artwork – either symbolic, political, historical, psychological, etc. This is seen as the natural role of art historians, curators, and art critics – a role whereby they put art in what is popularly called ‘the context’ as the final stage of an investigation. After reading the information that someone has given us about an artwork, you get the idea that everything you should know is there, written for you, and that the work is done accurately and with great precision.

When you come to a museum, the same thing happens – you follow the exhibit’s labels, and then follow the story written by a museum curator, and that is it. No matter how different ‘contexts’ one artwork can be put in, how many times you see it in different exhibitions, in different places, or used as proof of different artistic movements and ideas, at the end of the day you have that feeling that everything you heard is the truth. However, it is merely information which is served in front of you to drink, and to make you comfortable.

Even though some curators, art historians, or art critics want to make you believe that everything they say is true, it is not. One can never obtain all the information, especially when we are talking about ancient art. The curators, art historians, and critics are human beings; individuals who approach things differently, who see things differently, and who come to different conclusions about the same thing. Their writing styles are unique to them, based on their experiences. David Carrier (2003, p. 180) once wrote that “There are, it would seem, as many ways to interpret Warhol’s art as there are ingenious historians.”

Saying that does not mean that art critics are sharing mistakes intentionally or that they are making stories based on nothing. The first step of any research and writing on arts is usually having all accessible facts collected so that the researcher can then start digging deeper; but the main factor for being a good art historian, and writing something of great value, is making synthesis based on the facts that we obtained. In addition to information, you need talent, a creative power that pushes you to find and explain what others also see, but don’t know how to express. That is a true calling for an art researcher – making a story, a story about art that is not only a part of the process of having an inspiration but also inspires in itself.

As an art historian and museum curator, I approach artworks every day; I see them, I comment on them, I try to understand the circumstances they appeared in; what question caused this artwork to become an answer? When you approach artwork, especially seen for the first time, you are almost repulsed by it – because our need to know, to contain information, is stronger than our will to just see, without explanations. But that first contact with artwork is so important – it sets the stage for later conclusions, ideas, and routes you need to come through to write about it truly, without formality and banality. After the initial encounter, for me, the most important thing is to embrace that resistance and try to break it, not by making explanations to myself but just by watching, by constant staring if you will, as if there is nothing in front of me, nothing to look for specifically.

When I begin to decipher the visual experience, either with a painting, a sculpture, or an architectural work – the magic stops; I need to come close to it all over again, with the eye of a child. But being an art historian makes that a lot harder, because you already have folders in your head, and when you see an artwork, you instinctively start with ‘Oh this is a baroque influence’, or ‘There I see the beginning of a modern painting’, or ‘This is a homage to…’ Without even going deeper, you already put some prejudice into your work. It’s way harder to look at artwork in itself, without connecting it to the history of art, which is, as I said, based on prejudice. John Berger wrote, in his essay Between Two Colmars written in 1976 (cited in Overton, 2017), that we have to stop believing that the past is one-sided and rooted in history and concluded: “The first time I saw the Grünewald I was anxious to place it historically. In terms of medieval religion, the plague, medicine, the Lazar house. Now I have been forced to place myself historically.”

That is why I like going to exhibitions with children or with people to whom the world of art actually is a strange world – or is it that art historians and our culture made them believe in that?

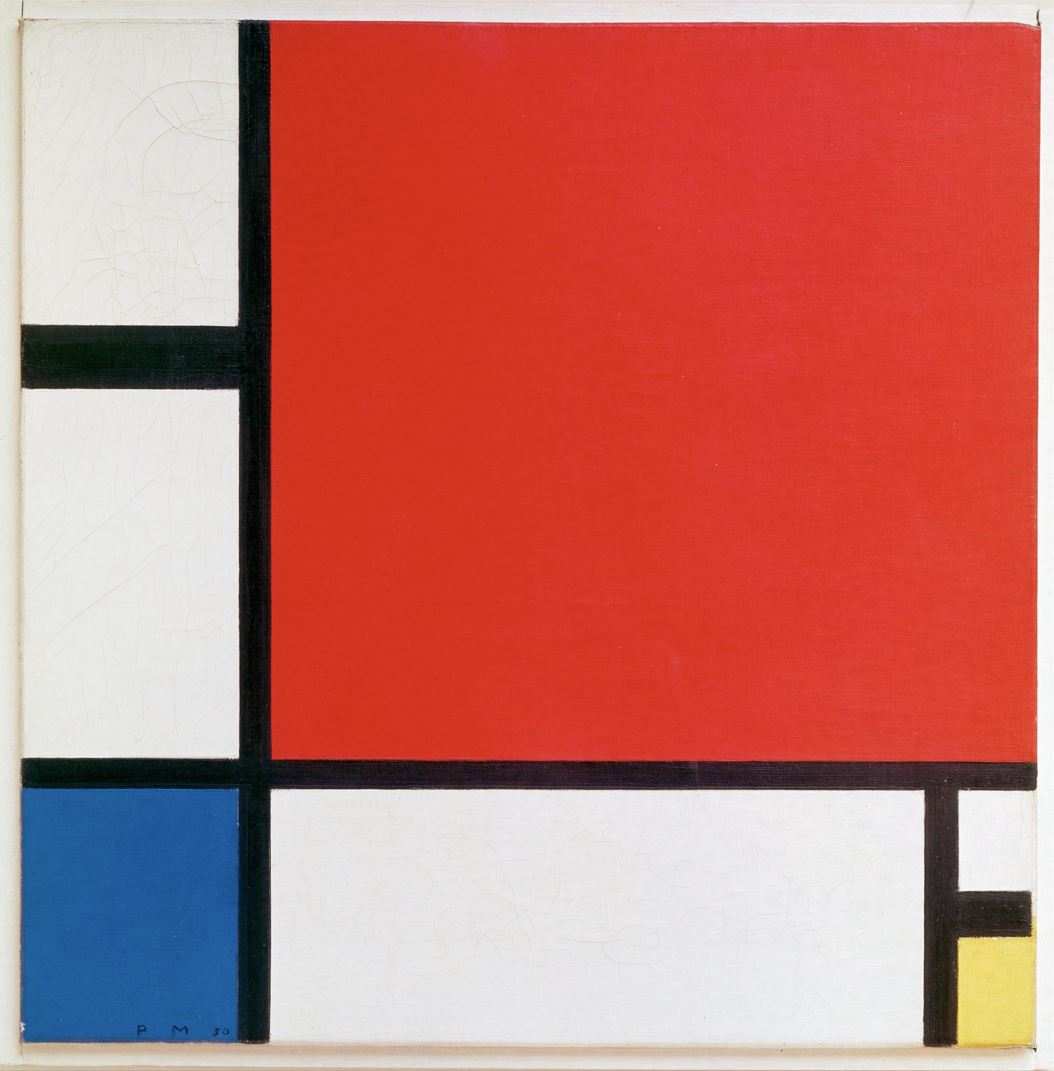

‘Composition II in Red, Blue, and Yellow’ by Piet Mondrian, 1930. 45 cm × 45 cm. Image in public domain.

I have introduced a known Mondrian painting from his abstract period to my friend, who thinks that art is not for her. I tried, as a proper art historian, to explain how those lines and coloured squares represent infinity, that that painting has some deep meaning, that of cosmic order, great open spaces and infinity. However, she just looked at me and said, ‘no, quite the opposite, when I saw it I thought how narrow it is, and how it reminds me of something very enclosed, like a carpet.’ I was shocked, and for a minute, I even despised her reply, and thought that she knew nothing. But after a few days, those words began to make more sense, and I started envying her, for having the ability to see and read artworks just as they are. Later I often used the insights I gained from people who ‘don’t know anything about art’, and I realised I also have the power to stop my mind from taking too much from that accumulated knowledge. In that way I can find inspiration when approaching an artwork. I purposely throw away the knowledge I have, and look at the things that unfold in front of me. I walk around the art pieces, if possible; if not, I change the distance of looking at artwork, and I try that many times, until I believe I can seize the essence of an artwork.

![‘No. 61 (Rust and Blue) [Brown Blue, Brown on Blue]’ by Mark Rothko, 1953. Oil on canvas. 292.74 x 233.68 x 4.45 cm. The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles The Panza Collection. © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko ARS, NY and DACS, London 2023. Permission to use granted from DACS, London 2023.](https://www.poeticmind.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Mark-Rothko-No.-61-1953.jpg)

‘No. 61 (Rust and Blue) [Brown Blue, Brown on Blue]’ by Mark Rothko, 1953. Oil on canvas. 292.74 x 233.68 x 4.45 cm. The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles The Panza Collection. © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko ARS, NY and DACS, London 2023. Permission to use granted from DACS, London 2023.

Some arts, like Mark Rothko’s, require visitors to look at the paintings from a certain distance, because of the feeling the works can give you that way, and that is true – but at the same time, not believing everything an artist claims is also an important part, following the path of inspiration and creation. But if I have to choose one quote from Rothko that I really believe in (cited in Overton, 2017), it would be this one:

“If I must place my trust somewhere, I would invest it in the psyche of sensitive observers who are free of the conventions of understanding. I would have no apprehension about the use they would make of these pictures for the needs of their own spirits. For if there is both need and spirit there is bound to be a real transaction.”

After that encounter with pure visual aspect, I give it time so it can grab me, and pull me into it. When I am finally without pre-conceptions – some spark comes to my mind, the spark of inspiration, and creativity unfolds.

I like to bring some paper and a pencil with me, and to write down everything I feel when in front of an artwork. First, emotions; second, the creative instinct of an artist that, at that stage, can become visible, even tangible; and third, aesthetics – the moment where I try to make a puzzle of what just happened and how it is connected to the visual qualities of the picture. Those three things overlap as I outline my work, and words, sometimes strange and difficult to understand begin to fill up the paper. I am outside the whole process, but actually more present than in every other task I do. After this initial moment, which sometimes takes hours, I again allow myself to invoke what I intentionally forgot, and to get my knowledge back, just as a tool, to write something that is creative and understandable, to arrange words into some kind of order. Sometimes the majority of the text is written with that creative impulse. The impulse acts as a creature from an artwork that eats me and spits me, and I forget where I am, and even how to speak. Sometimes the rational side of my brain eats the artwork and as it chews what I see, words come as the result. Both processes happen fast, and after that I feel a bit drained, but satisfied, as I bring the unknown, the pure, the archetypical, the primordial on the surface. That is, in my opinion, the process of creation itself.

People are mistaken when thinking that art historians know something others do not know, some kind of truth. I think people should not be scared of their encounters with art. Either way, they may feel resistance at first if they are really looking, if there is no pretending. That is, I believe, the only way to encounter an artwork or to write about it. At least for me – creation hits where the knowledge is absent, where the past is unknown; where the only important thing is that moment of looking, and seeing, without the need to make something valuable out of it. It is similar to what Stevens (1947) wrote, in his poem ‘Credences of Summer’:

“Let’s see the very thing and nothing else.

Let’s see it with the hottest fire of sight.

Burn everything not part of it to ash.”

© Journal of Creativity and Inspiration.

Images copyright as specified.

Katarina Đošan received her Master’s degree from the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Belgrade, Serbia. Her thesis concerned the question of the history and methodology of art history, as she was intrigued by different approaches but similar forms of art historian writings. She works at the National Museum of Serbia as an archivist and a curator, handling and researching archival documents, artists’ legacies, sketchbooks, and photo documentation. She also writes for the online magazine PLEZIR, based in Serbia, on art, sustainability, and culture.

References

Baxandall, M. (1979). The language of Art History. In New Literary History, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 453-465.

Carrier, D. (2003). Art History. In Critical Terms for Art History. The University of Chicago Press.

Overton, T, ed. (2017). Portraits: John Berger on artists. New York: Verso.

Stevens, W. (1947). Credences of Summer. In The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens (1971 edition), New York: Alfred A. Knopf.