FEATURE

Biomimicry: the natural world as a classroom

14 February 2024 – Vol 2, Issue 2.

Biomimicry is a research field that aims to inspire solutions based on designs we see in nature. These designs tell us a truly remarkable story of ingenuity and wonder. A story about structures, configurations, patterns, and strategies that provide solutions to incomprehensible challenges mounted for survival. It’s a tale of fierce battles won to avoid extinction, of unsung heroes small and large living around us.

When the natural world becomes our classroom, the outdoors our hi-tech laboratory, and the environment our mentor, then every experience becomes an inspiration. Our world teems with billions of life forms that have existed for aeons and have mastered the art of survival with intelligent strategies that conquer every obstacle they encounter.

Gecko-inspired adhesive is used for climbing pads. Left: Photo: © Eric Eason / Biomimetics and Dextrous Manipulation Lab, Stanford University. Permission to use photo obtained from Dr. Elliot W. Hawkes. Right: Gecko photo by Skitterphoto. Photo in public domain.

Everything that is occurring in nature contains knowledge and a capacity to solve problems. It carries within an innate intelligence which has undergone over 3.8 billion years of trial-and-error experimentation; time tested and proven successful in real-time. Every fossil is a backup copy of what worked and what didn’t work. Every living creature that has evolved is a testament to strategies that work, and every mutation is nature’s way of asserting life that always finds a way to triumph over challenges.

There is a subtle yet powerful balance and harmony in nature as everything that exists on earth serves a purpose. Have you ever wondered how seasons never miss their timings? How do petals of flowers unfurl at the right moment? How does an ecosystem, like the ocean, support trillions of life forms with ease?

Chameleons: camouflage, and 360-degree vision. Photo from a video clip by Pressmaster, in public domain

The infinite palette of colours, intoxicating smells, patterns, sizes, shapes, and mysterious sounds are all epitomes of problems that have been already solved by nature. Imagine nature as one large organization where every flora, fauna and microbe has been employed to solve a unique problem. There is perfect coordination, exceptional communication, and precise information that provide a conducive environment for the survival of diverse species with different needs on land, water, and air.

In all things of nature, there is something marvellous.

– Aristotle

Here are some examples:

‘Friendships for a lifetime’: when organisms understand their limitations, they don’t brood over them, rather they strike friendship to help each other. An example is the friendship between corals and algae. The corals provide accommodation to algae, which, in return, provides food to corals as a tenancy deal.

‘Soul-touching love’: love isn’t only for humans; every creature experiences and expresses love in its own way. The great puffer fish fills the ocean floor with fabulous sand art for the love of its life. The bird of paradise puts up a grand tango dance for his mate, and peacock spiders perform a tap dance to impress their mate.

Did you know that even the intoxicating smell of rain has its story, a story about the survival of soil-dwelling organisms? When conditions around the organisms become unfavourable, these organisms cannot travel places in search of better areas since they lack limbs. So, they devised strategies to overcome their challenge – they simply hitchhike on insects whom they attract by producing their own alluring scent called Geosmin. Geosmin is a compound that gives rain its sweet muddy smell when the first showers of rain hit the ground after a dry spell.

At this very minute there are numerous ‘grand openings’ that are occurring in nature – petals that bloom, eggs that crack open to new life and magnificent butterflies that spread their wings as they emerge from their cocoons. Unconditional sacrifices are happening in the deep seas, such as octopuses’ mothers who invest a significant amount of energy into caring for their eggs. Nature is not just filled with bliss but also with harsh tactics and brutal scenes such as Butcherbirds that fork their prey on tree branches, or fungi that infect and then manipulate the behaviour of certain ants.

Nature is also home to the unexplainable which defies logic, such as the ‘walking seed’ that walks in search of a perfect place to germinate, or the Lungfish, also known as living fossils, that survive on land for months until rain hits the ground. Another example is the Thorny devil that uses its entire skin to soak up water from soggy sand. This allows it to drink with its feet and skin.

There are also powerful lessons that can be learned from nature’s ‘industry experts’:

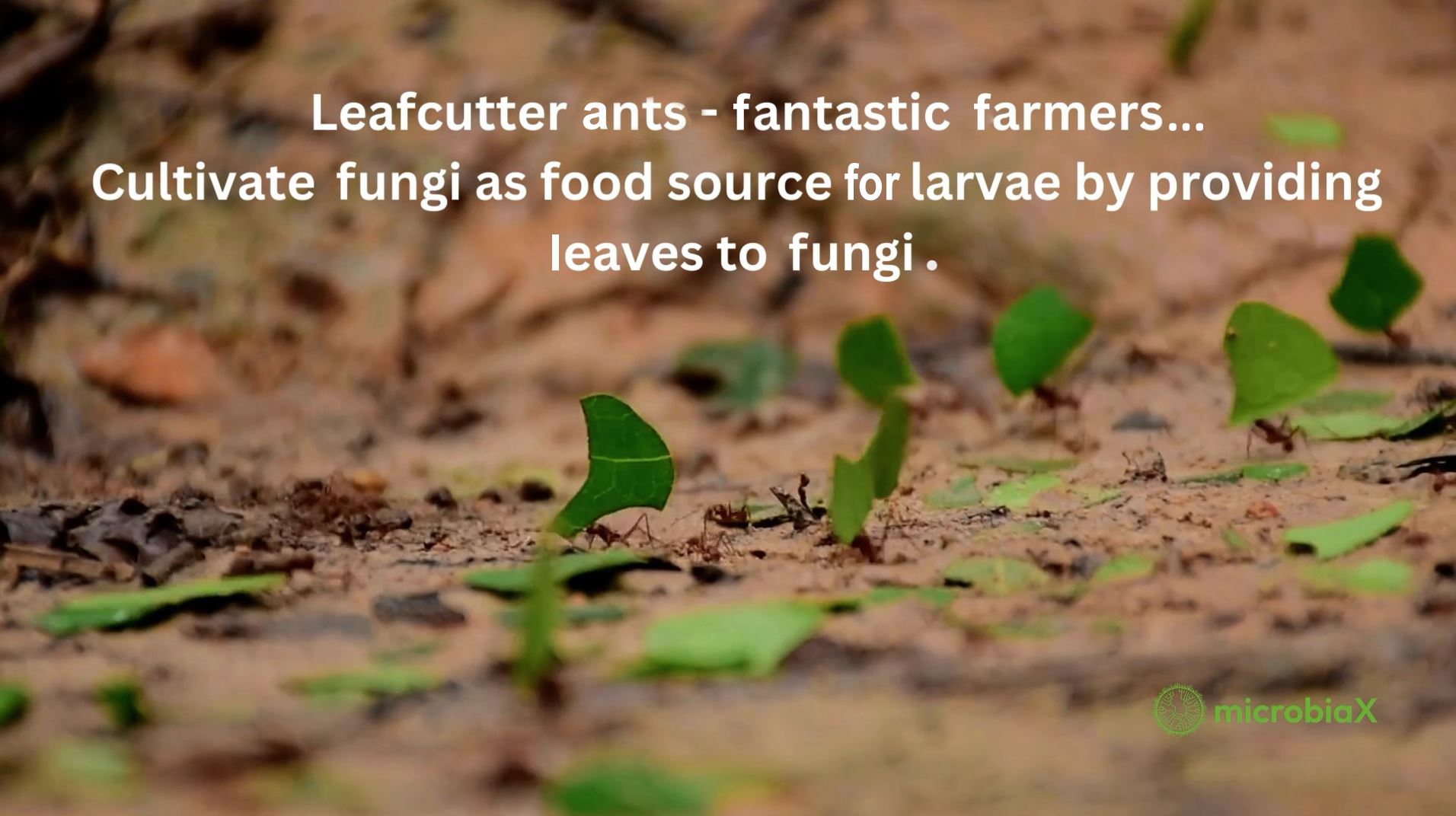

- The Leafcutter ant cuts leaves with incredible precision. They engage in a form of agriculture where they cultivate fungi for food.

- The octopus and Stonefish are experts at camouflage and can blend in perfectly with the environment.

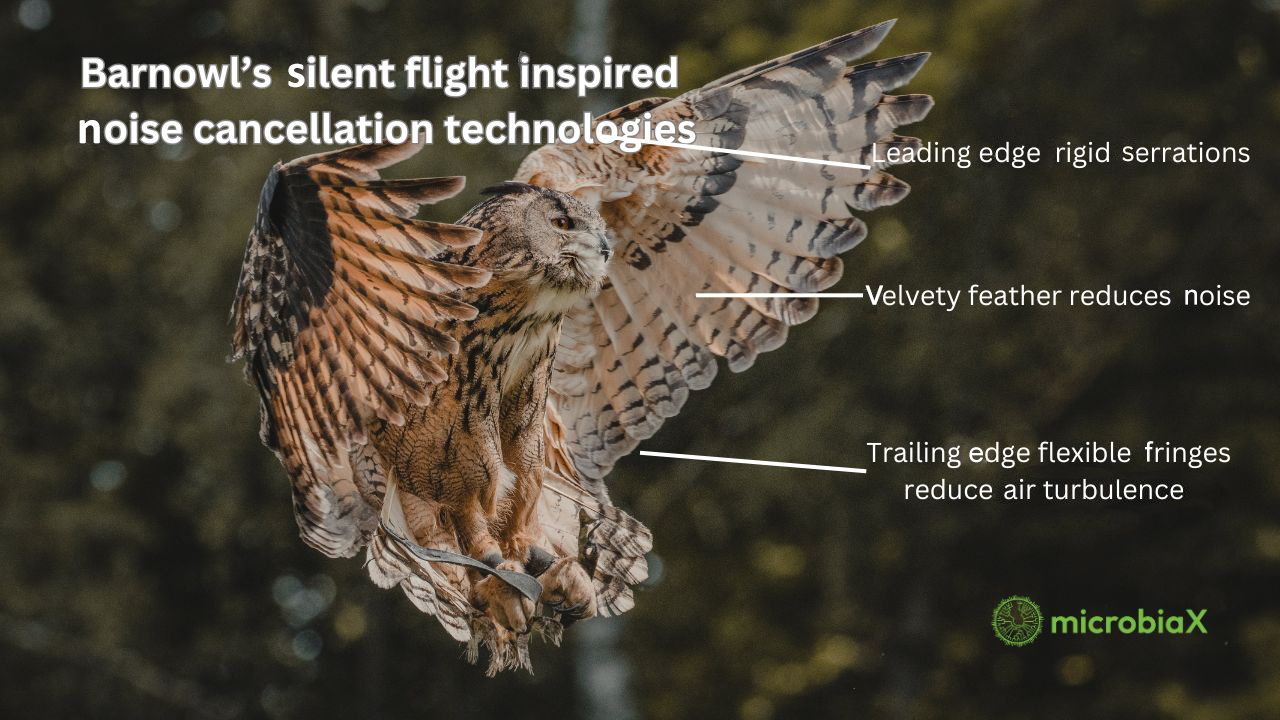

- The Barn owls are stealth fliers.

- Wasps build nests with complex patterns.

- Beavers, the ‘civil engineers’, build dams.

- Earthworms and fungi, the ‘soil engineers’, are nature’s cleaners and scavengers that devour dead and decay to keep our environment clean.

Leafcutter ants. Photo from a video clip by Gilmer Diaz Estela, in public domain.

Every creature has a strategy for survival, and a strategy for hunting, feeding, mating, navigating, and communicating. The art of learning these strategies and adapting them into designs that solve human problems is called Biomimicry.

Biomimicry endeavours to replicate nature’s functions, processes, and designs in the development of innovative technologies. People have always been intrigued and inspired by the beauty and mysteries of nature, along with its strategies that can help us solve human challenges. Solutions are hidden within every living creature on the planet, and our observation, interest, and learning from nature are the keys to unlocking the hidden power of its solutions to global challenges.

Biomimicry differs from Biomorphism. The term ‘biomorphism’ is derived from the Greek words “bios”, meaning life, and “morphe”, meaning form. Biomorphism is a design that takes inspiration from natural forms and structures. It resembles nature’s ‘look’. The hunting tools designed by the caveman resembled claws and talons. Hammocks resemble bird’s nests. These ‘artistic sculptures’ resemble the look of that which is found in nature.

Biomimicry is not a design that resembles the ‘look’ of how something appears in nature, but how it works in nature. Anything that is designed to ‘work like’ it functions in nature is Biomimicry. In other words, Biomimicry applies to strategies, processes, and functions copied from nature.

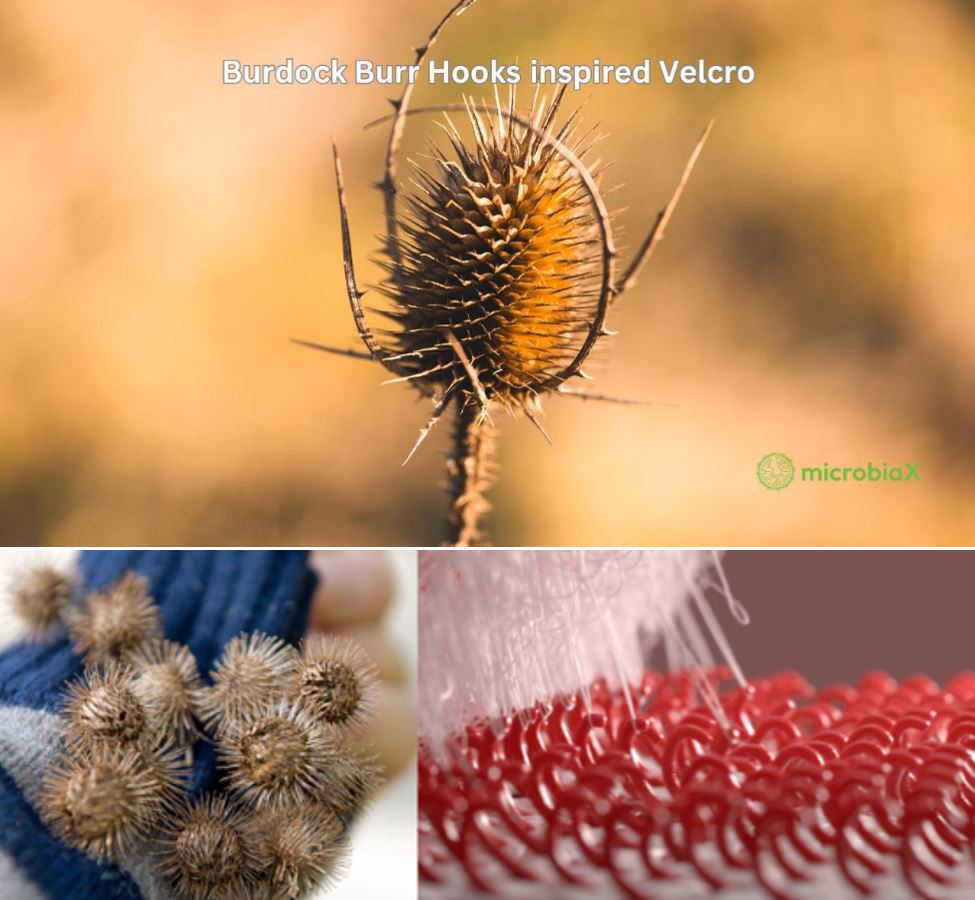

It takes a curious mind, the right question, and associative thinking to develop a biomimicry innovation. Such one curious mind was George de Mestral, a Swiss engineer. It was one pleasant evening when he was walking his dog. What seemed to be a routine, turned out to be a life-changing moment for this man. He noticed that there were small burdock burrs stuck all over his socks and his dog’s fur. Curious, he examined burdocks burr under the microscope, and was enthralled by what he saw. Millions of tiny hook-shaped protrusions which nature had designed to promote adherence – seeds that attach themselves, embarking on a journey for widespread dissemination. The more he pondered over this marvel, the more his creativity was ignited. This led to the amazing adhesive innovation he developed, called Velcro – the hook-and-loop fasteners that we all use. Just by asking the right question and having a curious mind, this Swiss engineer was able to transform nature’s hidden design into a practical solution for everyday use.

Top: Burdock Burr by Filip Steficar. Photo license: Creative Commons. Bottom left: Burrs hooked onto a woollen jumper. ‘Burdock (Arctium lappa)’ by Plant Image Library, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0. Bottom right: ‘VELCRO Brand Hook & Loop’ by Alexa Sirbu, Lukas Vojir, Zelig Sound, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

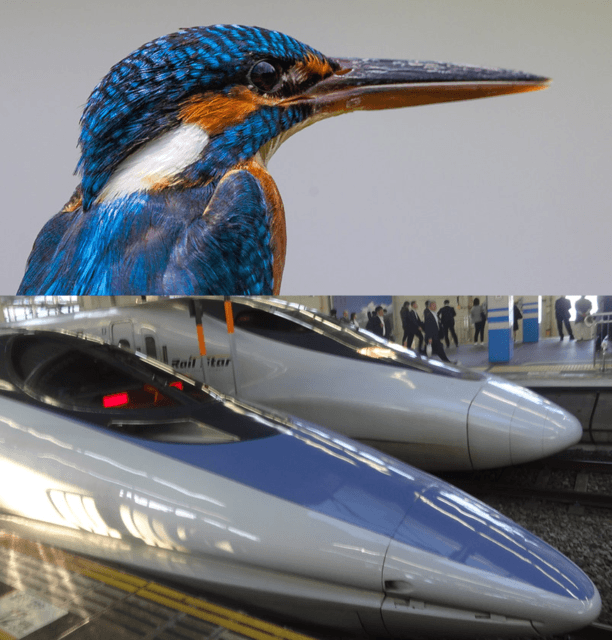

Nature finds ways to touch people’s souls and intellect in all corner of the world. Another person who was deeply inspired by nature to solve challenges, was the Japanese Eiji Nakatsu. Eiji was a nature enthusiast and an ardent bird watcher. One day as he was watching a Kingfisher dive into water to catch its prey, Eiju was captivated by what he saw. Kingfishers are known for their graceful diving capabilities. Upon close observation, he noted that the wedge-shaped beak of the Kingfisher played a crucial role in the bird’s ability to dive from one medium, air, to the other medium, water, without a splash and turbulence. He associated this incredible design with a challenge that he had to solve: Japan’s Shinkansen was the fastest Bullet train, but it had an issue. Every time the bullet train exited a tunnel it caused a blast sound that greatly disturbed those living near the train. He redesigned the train’s blunt nose to a shape based on Kingfisher’s long-pointed beak and the results of this redesign were stunning. It not only reduced the sonic boom but also increased the efficiency of the train and reduced fuel consumption. This one man’s design, inspired by nature, revolutionised Japan’s railway system.

The Kingfisher long-pointed beak inspired the bullet train. Photos: ‘Common Kingfisher’ by Olakara, licensed under CC BY 2.0. ‘Two Shinkosen’ by Yercombe, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

The architect Mick Pearce from Zimbabwe revolutionized the industry with his nature-inspired design and technology. The Eastgate Centre in Zimbabwe is a massive building and with the temperature soaring high, cooling the entire building with traditional methods was costly. Mick had to solve the problem of cooling the building with alternative means. Everything in nature holds a solution if only we could observe it closely and Mick’s solution came from the world’s tiniest architects, the termites. He observed that termite mounds are built as high as 2-4 metres above the ground and 2-4 metres below the surface. He pondered how could it be that ants are not cooked in the heat of the day nor frozen in the cold of night. How do they breathe at such depths and what maintains air circulation? When he studied the termite mounds, he was astonished by the most sophisticated construction design. The termite mounds had a main channel at the centre and branching sub-channels towards the sides, a perfect design that facilitated self-regulation of temperature and ventilation. He developed an improvised termite mound-inspired design for the East Gate Cooling system and with this he has inspired other architects to explore nature’s designs.

Nature-inspired technologies can be traced back to the Wright brothers who were the first to fly a heavier-than-air machine. This was inspired by the flight of birds. Leonardo da Vinci’s sketches of flying machines were also inspired by the flight of birds.

People from any sector or industry with any background can incorporate Biomimicry into their works. For instance, noise cancellation technologies have been developed by drawing inspiration from the acoustic features of Barn owls. Barn owls, also known as Stealth hunters of the night sky, take upon their prey in complete silence. Biomimicry experts have applied the serrations of Barn owl feathers, which give owls the ability to fly in silence, into designing noiseless wind turbines, fan blades and medical equipment.

Barn Owl. Photo by David Selbert, licensed under Creative Commons.

A Galapagos shark is a slow-moving shark. Despite its slow-swimming character, nature has devised a way to keep its skin free of barnacles and algae. The texture of the skin has sharp V-shaped denticles that prevent adherence. Inspired by these denticle texture designs engineers have developed self-cleaning surfaces which prevent bacterial adhesion in hospital environments. Another example is diatoms, a type of single-celled algae, with unique and intricate patterns that have inspired biomimicry in material science. Engineers study diatoms to design materials with specific properties, such as lightweight structures with high strength.

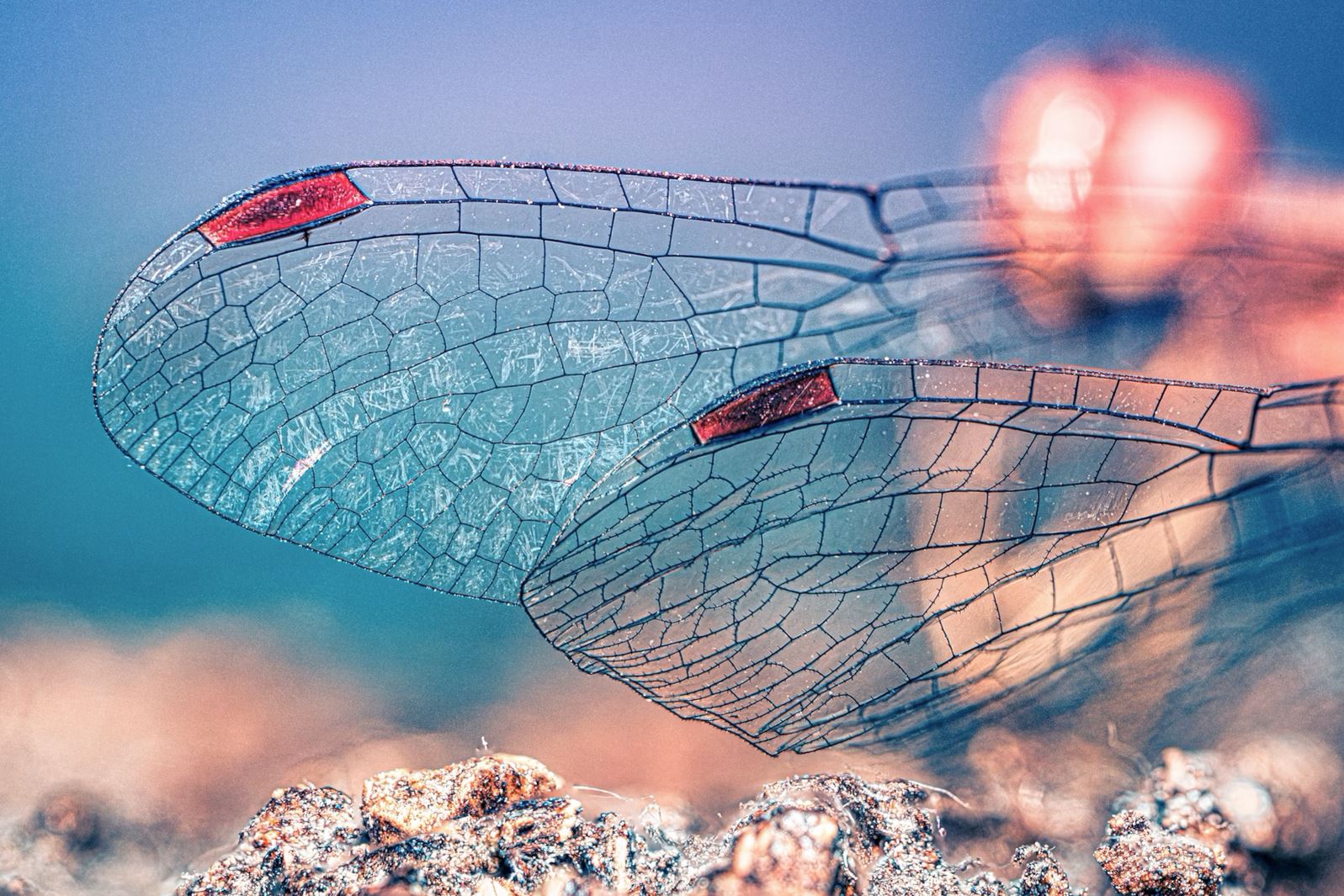

To become a biomimicry enthusiast, you don’t have to be an engineer or designer; you only have to look at nature, seeing nature as a teacher who has a solution to a problem you seek to solve. If for example, you are a material designer, ask yourself which living creatures are building materials in nature; a simple example would be a spider’s web, diatoms, or seashells. If you are an artist, you could ask yourself what patterns and designs of art are found in nature, like a butterfly’s wings patterns, or the wasp’s nest.

Shapes and colours found in nature. Close-up on a dragonfly’s wings. Photo by Megs Harrison. Photo in public domain.

Biomimicry also holds immense potential for the medical field. For example, we can draw inspiration from the self-healing process of octopus, the regeneration of Axolotl (aquatic salamander), and the swarm coordinated communication of birds and fishes.

Biomimicry can be more than a subject or a scientific field; it can be a lifestyle. It is the means through which humans connect with nature and understand their interconnectedness. Everything in nature is interconnected and interdependent. Our survival depends upon a healthy earth.

The key to unlock the secrets of nature lies in asking the right questions – how has nature solved this? Which creatures are facing the same problems that I am trying to solve? What aspect has been used to solve the issue, through texture, shape, function, process, colour? How would nature solve the problem?

Biomimicry holds a promise for solving climate crisis issues. Biomimetic designs are sustainable, renewable and have zero waste. So, let us look up to the world’s most skilled and powerful problem solver – nature.

© Journal of Creativity and Inspiration.

Images copyright as specified.

Sajeetha Kannan is an Industrial Biotechnologist. She began her career as a Lecturer of Microbiology and has been a Scientific Database consultant. She is currently a biomimicry enthusiast, speaker, and entrepreneur. She is also the founder of microbiax, a scientific initiative to teach, train and research biomimicry and microbial biomimicry.