Vision and Ekphrasis

14 February 2024 – Vol 2, Issue 2.

How we attend to and respond to works of art transforms not only what we see in the image before us, but what we might glimpse through it – and in the process, what we might discover about ourselves. Today, our attention is increasingly limited to the surface of images, through shock, or ‘wow’, with fleeting flights of the mind that do little to create any lasting effect. Fortunately, Ekphrasis (pronounced EK-phrasis) is a form of writing about art which helps to engage a broader, deeper form of attention by taking us into participation with a work of art, and might, in the process, help us contemplate the nature of being.

Ekphrasis is considered one of the oldest forms of writing about art in the West. Its etymology from the Greek means exposition, to speak out (ek – to speak, phrasis – out). Very different to how we might read a critic’s view of art, ekphrasis is richly descriptive and moves us into a true spirit of knowing. It allows for questioning and having a sense of discovery, so that what we encounter opens something unique in both us and in the image, rather than closing it down.

Psychiatrist, neuroscientist and literary scholar, Dr Iain McGilchrist, explains that we have come to see ourselves and the world through an increasingly left-brained view. Through his hemisphere theory (McGilchrist, 2023) he has shown that it is in fact the right hemisphere of our brain that is able to attend to the world in a full ‘living’ sense. It sees the bigger picture, appreciates the implicit, the embodied, and the unique, and sees our relationship with the world as continually coming into being, in motion, and interconnected. Both hemispheres are responsible for almost all of the same faculties, but it is the way in which they do it that defines them. The only function the left hemisphere is responsible for which the right hemisphere is not, is language.

We may rarely acknowledge feelings of wonder, awe and even love, in our initial responses to works of art, and yet these are the most fundamental emotions which keep us very much human and in touch with the world. In fact, we have become separated from the world and each other to such an extent that we see a fragmented place around us, of which we are no longer a part. We need both hemispheres, argues McGilchrist, but it is the right hemisphere that will allow us not only to see the literal meaning in a work of art, but will enable us to see metaphor, to understand art as a living force and participate in it, as something we behold and that can behold us. When we add to this the left hemisphere’s role as ‘servant’ to the right hemisphere, and its governing of language, the left hemisphere might then be able to translate that vision into words.

In the past, works of art were created with great beauty – and meaning within their beauty. Meaning was implicit, requiring imagination and intuition, so to translate them into a deeper wisdom. In his research on the Renaissance, Edgar Wind writes that many works of art were created to awaken the soul and divine in both the viewer and in the image, but not in an explicit way as we might attempt to do so today. The words we have to describe them should in some way take the form of the poetic, as he writes: “The divine ray cannot reach us unless it is covered with poetic veils” (p. 14, 1968). Through and between both the viewer and the image, something is brought forth, and we not only see it but are seen.

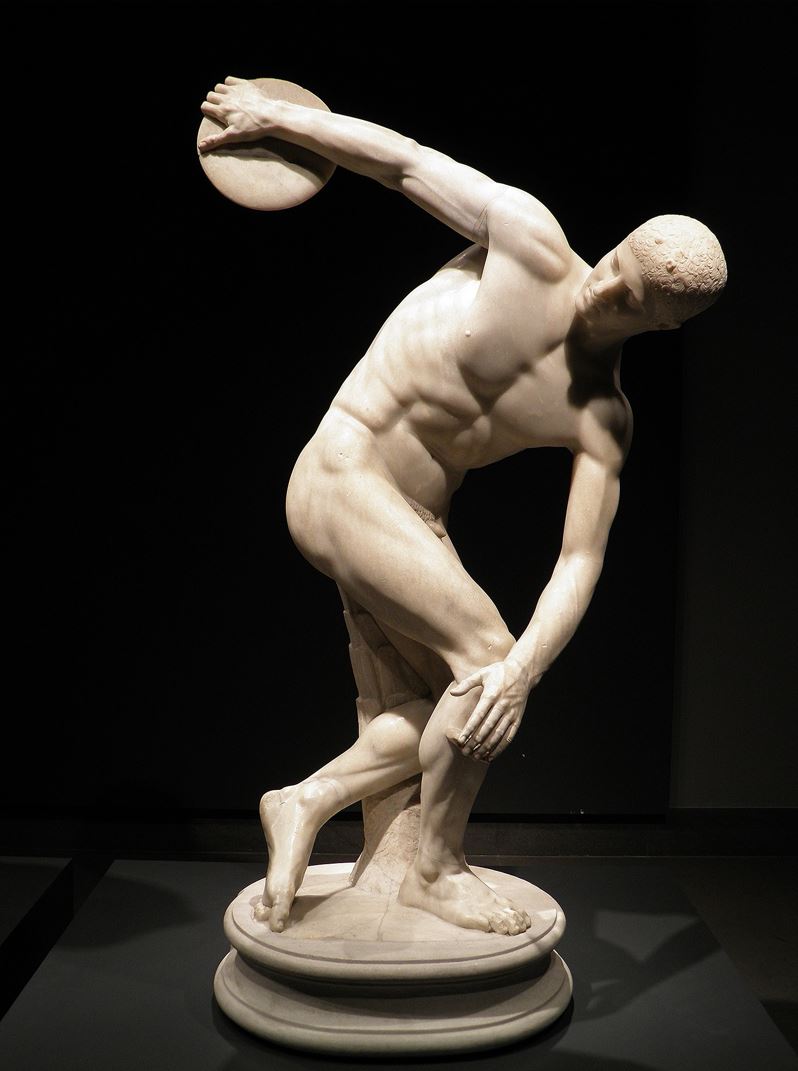

Ekphrasis is a vividly descriptive form of writing, staying with the image while allowing the imagination to come into play alongside a sense of reason and revelation. For ancient civilisations, particularly ancient Greece, art was something animate and alive, especially statues. Statues could inform people’s ontological understanding and broaden ways of knowing and seeing beyond the image. People were invited to move into a deeper knowledge of the world and see how they might play a role in it. The human body was central to this, not to impose a human-centric stance on the observer, detached from the world, but to show that the human being was a smaller expression of the cosmos, not the cosmos itself. And so, our part within a larger scheme of things was established, replacing hubris with humility. The proportions and form of the human body we see in Greek statues are often based on symmetria, “the dynamic counterbalance between the relaxed and tensed body parts and between the directions in which the parts move” (Polyclitus’s Canon and the Idea of Symmetria, n.d.). They are asymmetrically harmonious, balanced and reveal implicit movement in stillness, as we see in Myron’s Discobolus.

A copy of ‘Discobolus’ by Myron. This is a 1st-century AD Roman copy of the original (original from 460–450 BC), National Roman Museum in Palazzo Massimo alle Terme. Image in public domain.

This is relevant to us today. While we live in the modern world where these cosmological principles are no longer explicitly displayed in public statuary or through rituals, their philosophical and sacred implications supersede time and place, and their beauty still touches us. They still might have something to tell us if we stop and listen.

The ancient Greeks invented ekphrasis whose purpose was to make the reader envision the thing described as if it were physically present. In many cases, the subject never actually existed, making ekphrastic description a demonstration of both the creative imagination and the skill of the writer. For readers of famous Greek and Roman texts, it did not matter whether the subject was actual or imagined. The inner is not separated from the outer. There is a synthesis between the power of the imagination to see ‘images’ through the inner eyes (for the Greeks these would be the Ideas, situated in the Intelligible realm of the soul), and what might exist externally in the world in the form of images. The purpose therefore in creating an image was to bring into material form a tangible expression of a higher level of consciousness, higher than human’s. Yet, it is filtered through the human brain and mind, touched with the unique skill and eyes of the creator – artist, sculptor. The texts existed and were studied to help form habits of thinking, to form phantasia (the imagination proper), and to develop the skill of writing, and not as historical evidence.

If the image written about was real, then the image was seen in new ways and took on a life of its own. It could be brought to life, as in the Greek story of Pygmalion (later re-told by Ovid) who brought his statue to life. Through ekphrastic writing, the emphasis is on expression, movement, creating a birthing of something – creativity in the writer as he/she is, in turn, brings an image to life through the writing – which in turn comes into being for the reader.

But there is another aspect of ekphrasis which is important for our understanding of creativity and imagination. Rather than taking us away from the world or becoming swept up into what Carl Jung would have called “an all-enveloping phantasmagoria” (Chodorow, 1997, p. 12), the continual oscillation between reader/seer acts as an anchor that provides some boundaries within which to work. Without boundaries, writing or art of any sort may end up becoming part of post-modernism (not to be confused with all art created in the post-modern era), which does not offer creative freedom or insight, as it takes away restriction of any sort. One is set adrift emotionally into a meaningless void where ‘anything goes’.

Conversely, in Renaissance painting, Leon Batista Alberti instructed painters to know about all the movements of the body from the deep observation of Nature and the practice of drawing, for “It is extremely difficult to vary the movements of the body in accordance with the most infinite movements of the heart (Alberti, 1972, p.77). The ‘infinite’ is held within an overall geometric and mathematical framework of perspectival depth and space, the combined result of which is what was considered, decorum. Furthermore, through its emphasis on the visual, on detail and the whole, ekphrasis keeps the imagination turning back to the phenomenological, the tasting, smelling, sensing, hearing, seeing of what it means to be a human being in a body experiencing the world.

Ekphrasis is first expressed in Homer’s Illiad, where he is describing Achilles’ shield. From here on, different visual interpretations of the shield were created.

The shield’s design as interpreted by Angelo Monticelli, from Le Costume Ancien ou Moderne, ca. 1820. Image in public domain.

But essentially the cosmos (heaven and earth) is revealed in the images of the shield, with the earth, the sun, the sky, the moon and constellations in the centre of the shield, layering out to abundant imagery of civilisation. Farming, harvesting, people, and the ocean around the edge, all held within the ‘sphere’ of the shield, which becomes a visual metaphor for the cosmos. W. H. Auden’s Shield of Achilles published in 1957 was written ekphrastically, and so this form of speaking and writing about art is not a task reserved solely for the ancients. This is something which can still ‘speak’ to us today.

After the collapse of the Roman empire, ekphrastic writing almost disappeared, until the early Florentine Renaissance, the seeds of which are to be found in the writings of Dante and the art of Giotto. Dante described in vivid detail the sculptures carved on the white marble wall just inside the gate into Purgatory, revealing the strength of his responses to the expressive qualities in works of art awakening in the imagination. His senses do not see the Angel as carved, but as real, for he hears the sacred whispers exchanged between them.

The Renaissance humanists revived the ancient rhetorical form of ekphrasis for its ability to make the reader/listener feel as if they were a participant in the visual experience. The works of art they created were some of the most beautiful that have ever been created in the history of the West, and it is partly due to ekphrasis that they seem to come alive. Dr Marjorie Munsterberg remarks that the rebirth of ekphrasis in the Renaissance took on its own turn: “the rhetorical form became an important literary genre and, in a surprising twist, artists made visual works based on written descriptions of art that had never existed” (2009, p. 8).

The Roman writer Pliny describes a relationship the Renaissance patrons might well have wanted to establish with their painters (Ames-Lewis, 2000, p.189). Patrons could order paintings that would recreate lost classical paintings, even if those classical paintings were only ever written about, or a description of a painting the writer claims to have seen. Descriptive details written in classical texts began to make their way into Renaissance paintings. Regardless, as Professor Ames-Lewis points out:

“Emulation of the described qualities of these paintings brought intellectual prestige to both patrons and artists … partly because the paintings had often been made by renowned classical artists … and because the literary conventions on which the genre of ekphrasis was founded resulted in descriptions that were both pictorially richly elaborate and often intellectually sophisticated” (2000, p.190).

In the 15th century, the Renaissance humanist Angelo Poliziano describes the reliefs cast by Vulcan for the Doors of the Temple of Venus, revealing how the observer can bring about a deeper understanding of the image through imagination. He writes: “Whatever the work of art does not possess within itself, the imaginative mind understands clearly …” (Ames-Lewis, 2000, p. 193).

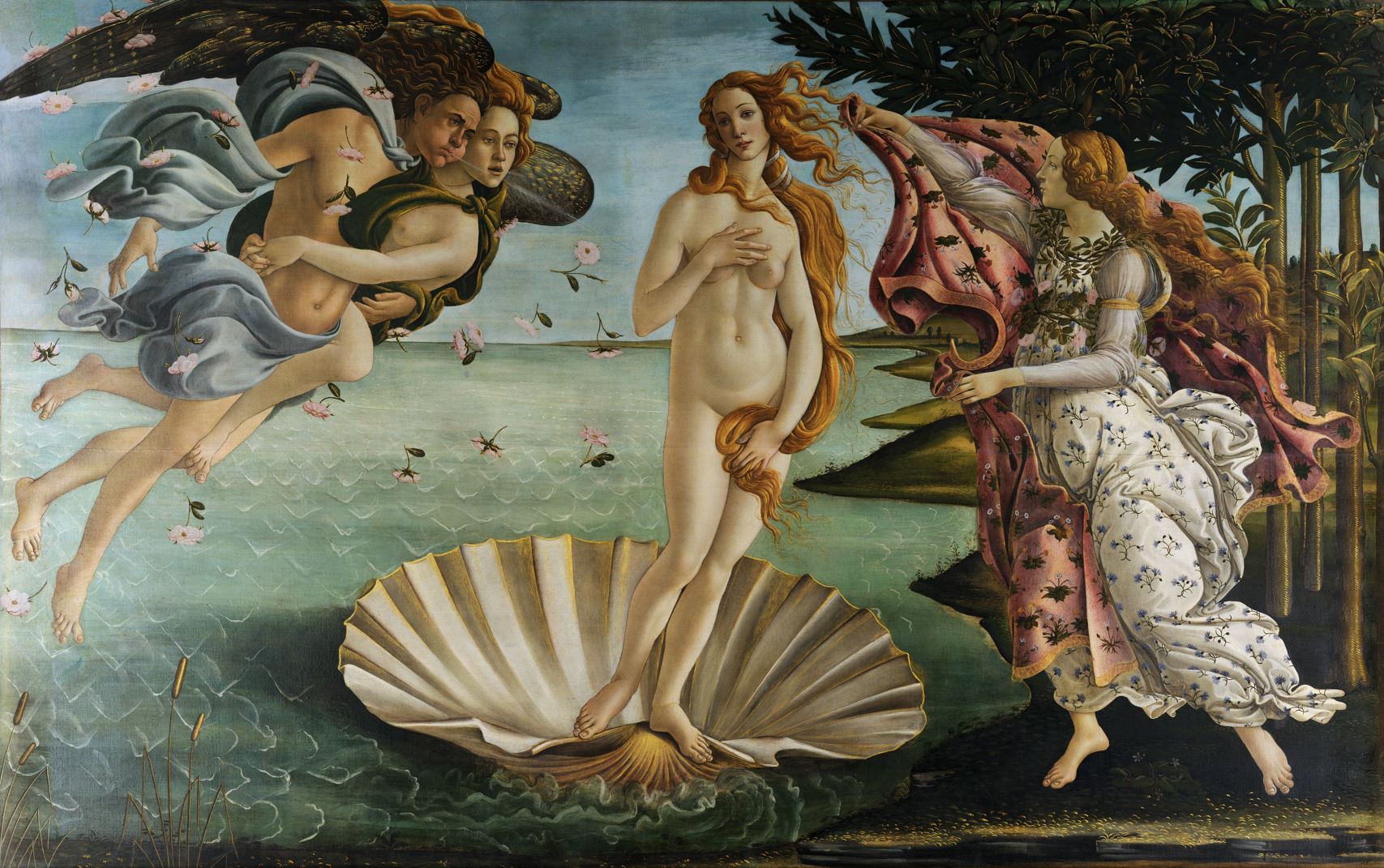

When Botticelli painted the Birth of Venus in the mid 1480s he must have been aware of Poliziano’s description of Vulcan’s relief, as Poliziano writes: “the sea and the foam appear to be real, the wind seems to blow, and you would seem to see trembling air in the hard stone (Ames-Lewis, 2000, p. 193).”

‘The Birth of Venus’ by Botticelli, 1480s. Uffizi gallery, Florence. Image in public domain.

Poliziano also takes Ovid’s account of the story of the Birth of Venus, and in turn, Botticelli’s masterpiece reveals his interpretation by painting the creative imagination and the poetic. The long-standing fascination we have with older works of art, must, in part, have much to do with both their obvious beauty and their hidden depths. We need great works of art such as The Birth of Venus, for as humans, we are shown qualities that remind us of who we are and who we might become, even though that may never be attained. A work of art says the unsayable, which we recognise, and can redeem.

Ekphrasis had its own renaissance in the Victorian era, through the writers John Ruskin and Walter Pater among others, and their predecessors: the Romantic poets, Byron, Keats, Shelley and Wordsworth. Ruskin was a strong supporter of the artist J.M.W. Turner, and through his writing, Ruskin shows us a different view of the world, a way in which it might be enhanced through our quality of attention. In his diaries, Ruskin writes:

“Free-heartedness, and graciousness, and undisturbed trust, and requited love, and the sight of the peace of others, and the ministry to their pain; – these and the blue sky above you, and the sweet waters and flowers of the earth beneath; and mysteries and presences, innumerable, of living things – these may yet be your riches” (Fagence Cooper, 2019, p. 25).

Ruskin’s words show how we might see anew the living breathing world around us. Turner painted nature in much the same way as Ruskin saw it and wrote about it. It was a means to telling the truth about the world in all its beauty and in all its disruption, too. Living during industrialisation and the mechanisation of the world, Ruskin saw how the sunset colours, which Turner painted, changed due to growing pollution, along with the movement of people and their plight. Ruskin wrote an ekphrastic response to Turner’s painting, Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying – Typhoon Coming On, 1840. As a deeply religious man, Ruskin’s description is influenced very heavily by his reading of the King James Bible, so his written response to Turner’s image is sermon-like, dramatic, emotionally charged and deeply moving.

‘Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying – Typhoon Coming On’ by J.M.W. Turner, 1840. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Image in public domain.

Ruskin’s example of an ekphrastic piece of writing suggests how we too might find a way in when not just looking at a work of art, but by starting to ‘breathe’ it so it comes alive in the soul and the heart. Our words can enable the listener/reader to see it in their imagination.

To experience art deeply, try this process:

Begin with a detail and literally describe what you see, so that your eye is led into the image and around and through it. Read your text to others (while they are not looking at the painting that you are describing to them) and ask them to visualise what you have written, and how they see it. Reflecting on your written piece, how might you then place it in a broader context of knowing? This might include researching the painting or statue’s historical origins, its philosophical implications as well as what it means to you personally.

John Ruskin presents an aspect of ‘seeing’ in its broadest sense, and yet without over-seeing or over-looking. Today, we have an over-surveillance approach to looking, and in doing so we miss out on the world. What the great ancient writers and artists – Dante, the Renaissance humanists, as well as Ruskin, Turner and McGilchrist – show us, is that we should not try to ‘see’ too much. Over-exposure to the sun leaves us blind. But through the poetic, through art and the beauty of the world, we can retain creativity and a sense of coming into being. Turner was not only inspired by Claude Lorrain but utterly adored him. McGilchrist describes the qualities of Claude’s effects of light, which Turner took up and transformed into his own inspired vision of the world, through paint. On Claude’s use of light, McGilchrist writes:

“Light is usually transitional, too, not the full supposedly “all-revealing” light of the enlightenment, but the half-light of dawn or dusk … in terms of the hemispheres, half-light and transitional states have a multitude of affinities with complexity, transience, emotional weight, dream states, the implicit and the unconscious rather than clarity, simplicity, fixity, detachment, the explicit and full consciousness (p. 361, 2009).”

The ‘implicit and the unconscious’ are right hemisphere qualities, and the ‘explicit and full consciousness’ are qualities of the left hemisphere.

The creative and visionary possibilities that are brought about through the practice of ekphrasis might evoke a deeper encounter with works of art. This is not to neglect the historical – far from it. It adds to the historical through our experience of the imagination – the right hemisphere – nudged by the work of art that catches our attention. Without the hard and fast assumptions of the left hemisphere, a way is opened that can lead us out of the dark and into an enriched vision of the world.

© Journal of Creativity and Inspiration.

Images copyright as specified.

Mary Attwood is an art historian, author, teacher and mentor. She is co-founder and director of Channel McGilchrist, co-director for The Centre for Myth, Cosmology and the Sacred, and was the founding Chairman of the Victoria branch of The Arts Society. Mary’s teaching and research seek to offer a broader understanding of art, not as an object to be analysed, but as a bridge between seemingly disparate ways of understanding the world and our place in it. While honouring the historical, her approach is to recover ancient philosophical and spiritual approaches to art, with modern neuroscience, and depth psychology, which she believes can help us meet the complexities of modern living by offering a renaissance of humane values.

References

Alberti, L. (1972) On Painting. London: Penguin Books.

Ames-Lewis, F (2000) The Intellectual Life of the Early Renaissance Artist. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Chodorow, J. (1997) Jung on Active Imagination. New York: Routledge.

Fagence Cooper, S. (2019) To See Clearly – Why Ruskin Matters. London: Quercus.

McGilchrist, I. (2009) The Master and his Emissary. New Haven: Yale University Press.

McGilchrist, I. (2023) ‘Hemisphere Theory’, Channel McGilchrist. Available at: https://channelmcgilchrist.com/hemisphere-hypothesis/ (Accessed: 30 January 2024)

Polyclitus’s Canon and the Idea of Symmetria (n.d.) ARTH. Available at: http://employees.oneonta.edu/farberas/arth/ARTH209/Doyphoros.html (Accessed: 29 January 2024)

I visited the Scottish national art gallery today and I had a feeling when I was looking at Olive trees by Van Gogh, an urge to capture this feeling of awe in words, to declare its beauty to everyone anyway I can. Words being a medium to capture the beauty and contemplate the meaning of the works of art (Ekphrasis) is an excellent idea. This post sums all of it beautifully.