Installation artist Ken Devine interviewed by Gil Dekel.

Gil Dekel: Your art project Colours of the Sphere looks at the ways in which people create meanings with the world around them and especially with colours. [1]

Ken Devine: Yes, the project started ten years ago with a brief to work in a junior school. I had a six months’ residency then and I scratched my head for some time to find an idea for a project that I could do, and I just hit on the idea that you could ask anybody the question, ‘What is your favourite colour?’ You can ask a four-year old child, and you will probably get a response. And you can ask a ninety-four year old ‘child’ and get a response… [2]

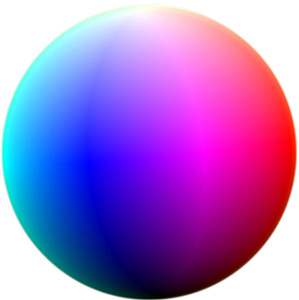

I am filming people’s answers, and the video clips are embedded in a three-dimensional simulation of a colour sphere which we created on the computer. You can navigate inside that sphere, focus on any specific colour, and watch the clips of people talking about that colour. [3]

What do people say about colours? [6]

People say remarkable things and it is not just to do with a favourite colour, but with anecdotes and short pieces of history about themselves. Usually people divide into different groups: the yellow people, the green people, the red people… The way I think about ‘groups of people’ has completely changed since the project begun. [7]

Some people talk about colours in terms of emotion, and this is a metaphysical relationship with colours. Other people talk about colours as an object, or event, or a person. And that is a kind of empirical relation with a thing that exists or can be observed. And then there are those who have a very clear rational idea as to their favourite colour. This is a kind of cognitive reasoning of the colour, which they try to contextualise. For example, they would try to explain why white is white. Or they would explain what the colour signifies by going into a chain of ‘because so and so, which is because, and because, and because’. It is a kind of a series of reasons for why a colour has an effect on them. [8]

I came across profound responses from people who were honest, rather than trying to be profound… [9]

Roughly speaking, these ways of how people respond are three central cores, and of course, any one person can move from one core to another. This is rather natural because of the changing nature of colour itself. You could think of colours in different ways, for example, in terms of hue/saturation/value or red/green/blue or in terms of primary/secondary. So, there are very interesting relationships between colours and the impossibility of it, and the impossibility of people… Someone can say something about red which is very similar to what someone else said about blue. That is ok, because it creates a new set of relationships that we may have not been aware of before. We are not talking here about single people, but about complex compound meanings. [10]

It is easy and complex at the same time, and I like this contradiction about reality. I think people can say contradictory things even in the same sentence, and such contradictions can make more sense than if you were just following a logical argument. With a logical argument you end up with an absurd position, because you are limited to logic. [11]

How can someone say contradictory things which still sound right? [12]

That is because behind the ‘simple’ things that people say lie complex relations that they have with life, and they use language to convey that. Language is illogical… like thought. Thought is illogical. [13]

What is thought then? [14]

Thought is an analogue process that includes the bits in between… It is saying something which is partly true and partly false. Rarely can you say a complete truth, a one hundred percent truth. The same goes for untruth. It is very difficult to say something which is a complete one hundred percent untruth. [15]

Language has that ability because we are dealing with a constantly changing dynamic environment, and changing meanings. People change continually. So, you have to think of all the gaps in between truth and untruth, and that is where most of us exist. It is about the difference between linear logic and non-linear logic. We are living in a non-linear world; we are not driving down the railway track. We are skating, we are wobbling on the ice, and you can go in any direction… [16]

I see human beings as model makers. We represent things by creating things, and our creations can be concrete or abstract, or feelings. All are equally valid creations. Now, the models by which we create can differ, for example, religious models or scientific models, and these models keep changing all the time; they evolve. Yet, the issues that they examine are the same. The issues are the human condition, the way we feel, the way we rationalise things and the way we interact with others. [17]

It is not the case that we have one perfect model that can provide us with all the answers. Science, for example, is a very useful model, yet it does not define the truth, because science itself is always in a stage of a flux; it is always asking more questions. The deeper the questions get the more poetic the answers come out… [18]

At the moment there is no relationship between the advances of science and happiness. Supposedly advances make life easier, simpler, and give people more free time, therefore we are ‘happier’. Ok, now let’s accept this argument and reverse it: by the Middle Ages everybody must have been completely fed up, depressed, and unhappy all of the time, because they were denied this ‘happy making’ technology that we have today… but of course that is not true. We do not say that in comparison to Medieval Europe we now have TVs and therefore we are happier. There is no sensible relationship at all here. Objects are not the driving force in life. It is the struggle which is the driving force. [19]

So, how would you approach this struggle? [20]

By looking at the meanings that we create. Meanings make our relationships with concepts and with objects. We are all some kind of rational cognitive self. We all respond to the physical world. The emotional aspect, above all, engages with others as well as with ourselves. [21]

How do emotions relate to meanings? [22]

If you feel something then there is a meaning. Maybe it is not rational, yet we do not live in a rational world. Rationality is about trying to construct those things which can be replicated, and create a kind of a rhythm. Rationality finds out what this rhythm is in a particular time. But that is a small part of what we do. We are not manufacturing motorcars most of the time, and when we do, we are not manufacturing them rationally. If there was such a thing as a ‘rational motorcar’ it would have been designed by now; it would be the perfect prototype from which all motorcars would be produced. But this does not happen, as we are constantly developing and changing the cars we produce. Take another example: if a chair was a rational object then the ultimate ‘chair’ would have been discovered by now and we would not need to keep creating so many different variations of it. So, all these chairs we are creating are expressive objects, objects with meanings, emotional objects. Whether we fully understand the meanings or not is another matter. [23]

Politics is example of great emotional art, based on rhetorical skills and persuasive arguments which do not have to be true at all. In fact, rational arguments are not useful in politics because they can be totally uninspiring… Whether something is true or false, that is a matter of position, a point from which we see it. [24]

An important part of the work is the point of view. You can navigate inside the colour sphere and choose a precise view of a colour. If you move the camera slightly you then change the position. For me, this relates to the way meanings are created through the point of view that we choose. It is about the position through which we see something, as well as what we actually see. It is about the way in which we frame what we see and thus frame what we decide to exclude. [25]

Does choosing a point of view affect the colour? [26]

In reality there is no definite place on the colour spectrum where you can draw a square and frame a colour within it. All colours are in relations to other colours. They sit side by side, diffusing one into the other. So there is always a difference between the beginning and the end of a colour. Red can sit between orange and purple, spreading into orange on one side and into purple on the other side. So, none of the colours exists in a sense, it is rather a set of relationships. There is no fixed place where you can see ‘that’s red!’ and in the same way you cannot fix the meanings of it. We have agreed on where colours start and where they stop, but there is no ‘stopness’ about red. [27]

We tend to think of colours as existing on points, but a point has no dimension, it is rather an idea. So that is about how much we can tell about the existence of colour – zero. What we are left with is a set of relationships between the points which create the spectrum. [28]

It is marvelous that there is this apparent concrete thing, colour, which the brain with the eye constructs. And we talk about it and wear it, we use it, we express ourselves with it. It is so concrete and yet totally abstract. There is a wonderful paradox to that, and everybody can give you an opinion on this paradox… [29]

What is your favourite colour? [30]

The one place I really find fantastic is the centre of the colour spectrum, the point between black and white, which is grey. It is the only place that has no complementary colour. Grey colour gets such bad press these days… we say, ‘What a grey day’, but grey is not completely depressing. It is not the total blackness of melancholy, and not the neurotic of total white… it is in between, like the Mona Lisa’s smile… it fights with nobody… [31]

Can we talk about how you became an artist? [32]

When I was fourteen I saw a programme about Frank Lloyd Wright, the American architect, and decided that I wanted to be an architect. I wanted to design falling water… I went to study architecture but the experience was far less art and far more structural. I had to design where to put the bins… Once the course finished I went to work as an artist for some time, and then I moved into furniture design. That coincided with having children and feeling the need to do something useful and productive… and so I made beds. Gradually the objects I made became more and more bizarre, up to a point that I realized I was making sculptures again… The objects I made lost their functionality, and they became questioning-objects rather than objects that answer questions. I had to admit it then… art was just what I had to do. [33]

What is inspiration in art? [34]

It is very complex, and I think there is inspiration in anything, not just in art. Inspiration, probably, is a uniqueness that comes out of parts of a person, which did not come together before. It is a moment of recognition that happens at the most unplanned events. [35]

Recognition of what? [36]

Of whatever it is that lit a fire in you. I am sure things happen all the time that could be potentially inspiring, but we have our eyes shut at them. We don’t hear them and we don’t see them. Inspiration is a kind of a moment of having your eyes open, and I think that can happen in every walk of life, in every moment. This is why I prefer to talk about ‘the art of…’ rather than saying ‘art is’…. Everything is an art of something: the art of painting, the art of cooking, art of walking, art of talking. Once we start to classify ‘art is…’ we then have to go into logical arguments which are bound to end with a confusion, because there are so many exceptions to it. Dance is art? Yes it is. Music is art? Yes. Painting is art? Yes. Now, how many different kinds of paintings there are? There are endless kinds of paintings, and endless kinds of what cooking is, what conversation is, what letter writing is. We cannot define everything and find a specific one definition. So, it is much better to discuss these in terms of ‘the art of cooking’, ‘the art of playing chess’, or ‘the art of drawing’. [37]

Art is as useful as football and as cooking food. You do not have to cook and you do not have to play football. Most objects which are designed, created and made – we don’t need them; they do not satisfy a real need in a way. However, they do satisfy one’s desire and they provide meanings, concepts and frameworks. Art is one of those things, a vehicle for meanings. [38]

So this art project might be a serious research project, but it might also be a wonderfully useless research… it has grown into this fantastic monster of meanings, and we keep adding meanings to it. What’s important really is to continue finding out new things and new relations in the meanings that people share with us. [39]

26 June 2008. Text © Ken Devine and Gil Dekel, Images © Ken Devine. Interview held in Portsmouth, UK, May 2008.

- Reading with Natalie, book here...

- Reading with Natalie, book here...